is also the anniversary of the death of a forgotten Little Current soldier

Jacob Baxter died on Vimy Ridge Day, April 9, 1917, age 20 …no longer forgotten

VIMY, FRANCE—On the morning of April 9, 1917, Jacob Baxter was among the living, a member of the 16th Battalion assembled in the tunnel/trenches that snaked across no-man’s land to bring them closer to the trenches defending Vimy Ridge. In the pre-dawn hours, just as the light of a new day brightened the horizon, two massive mines exploded beneath the German lines. One of the craters left behind by those explosions would become the last resting place of Manitoulin’s forgotten son.

Bill Mullen of Guelph, himself an Island expat from Little Current, has taken on the task of following the trail of Jacob Baxter, dimmed though it might be by the dust of a century past, even as 25,000 Canadians gather at the Vimy Ridge Memorial to remember and honour the fallen.

Jacob Baxter was born in Little Current on October 6, 1896. His mother Alzona married four times between 1890 and the early 1900s and his siblings/step-siblings included William, Robert, Sarah, George and Arthur Baxter, Joseph and Rosanna Brandow, Charles Baxter, and Sadie Rozander. You won’t find his name on the Island cenotaphs (he is on the one in Lethbridge, but his name is misspelled there) and if not for the diligent efforts of Mr. Mullen, his Island connection would likely have remained lost in the mists of time.

Mr. Baxter’s family moved to Kootenay, British Columbia and he later moved to Carmangay, Alberta, where he listed his occupation as chauffeur. On January 3, 1916 he enlisted as a private (Pte.) with the 113th Battalion of the Lethbridge Highlanders and after a few months of training he arrived in England on October 6, 1916. He was transferred into the 17th Battalion and with barely two days to find his land legs after the trans Atlantic crossing he found himself once more aboard ship, destination France.

Losses on the front lines were heavy during the Great War as it came to be known, the “war to end all wars,” today we know that global conflict as the First World War (WWI). Pte. Baxter’s unit was again transferred, this time into the 16th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF).

What followed were five months in brutal front line conditions. In those mid-war years, the British high command, despite the immense evidence laid out before them in an unimaginable butcher’s bill of casualties, were still convinced that a major breakthrough was at hand, if only the push was a little harder, the artillery a bit more focussed. As a result, the living conditions in the Allied trenches were abysmal.

For five months Pte. Baxter fought in the muddy fields near Arras, seeing action at the Battle of the Somme and Vimy Ridge. On April 9, 1917, Pte. Baxter became one of 3,598 Canadians killed in the attack we now know as Vimy Ridge—the rest of the world knows it as the opening engagement of the Battle of Arras. That battle itself was just a diversionary assault in support of the French Nivelle Offensive. The French had taken 150,000 casualties in their earlier attempts to take the ridge. The British took over from the French and a period of stalemate ensued that was characterized by intense shelling and desultory attacks.

In their turn, following a sustained period of detailed training and planning, it was the Canadian Corps’ turn to enter the maw of the meat grinder. In the three days of the battle for Vimy ridge, the Canadian Corps sustained 10,602 casualties, more than two for every one of the 4,500 yards gained in the attack. In Great War terms, it was an outstanding success.

When the exchange of counterattacks and shelling settled down, a British officer was assigned to gather up the dead and intern the bodies. One of the mines that was set off that day provided a ready-made hole for a mass grave for the 57 nearby dead, 15 of which remain “known only to God” (unidentifiable). The cemetery was then designated CB2A, later to become known as the Lichfeld CWCG Crater Cemetery. (The other crater is known as the Livy Crater.)

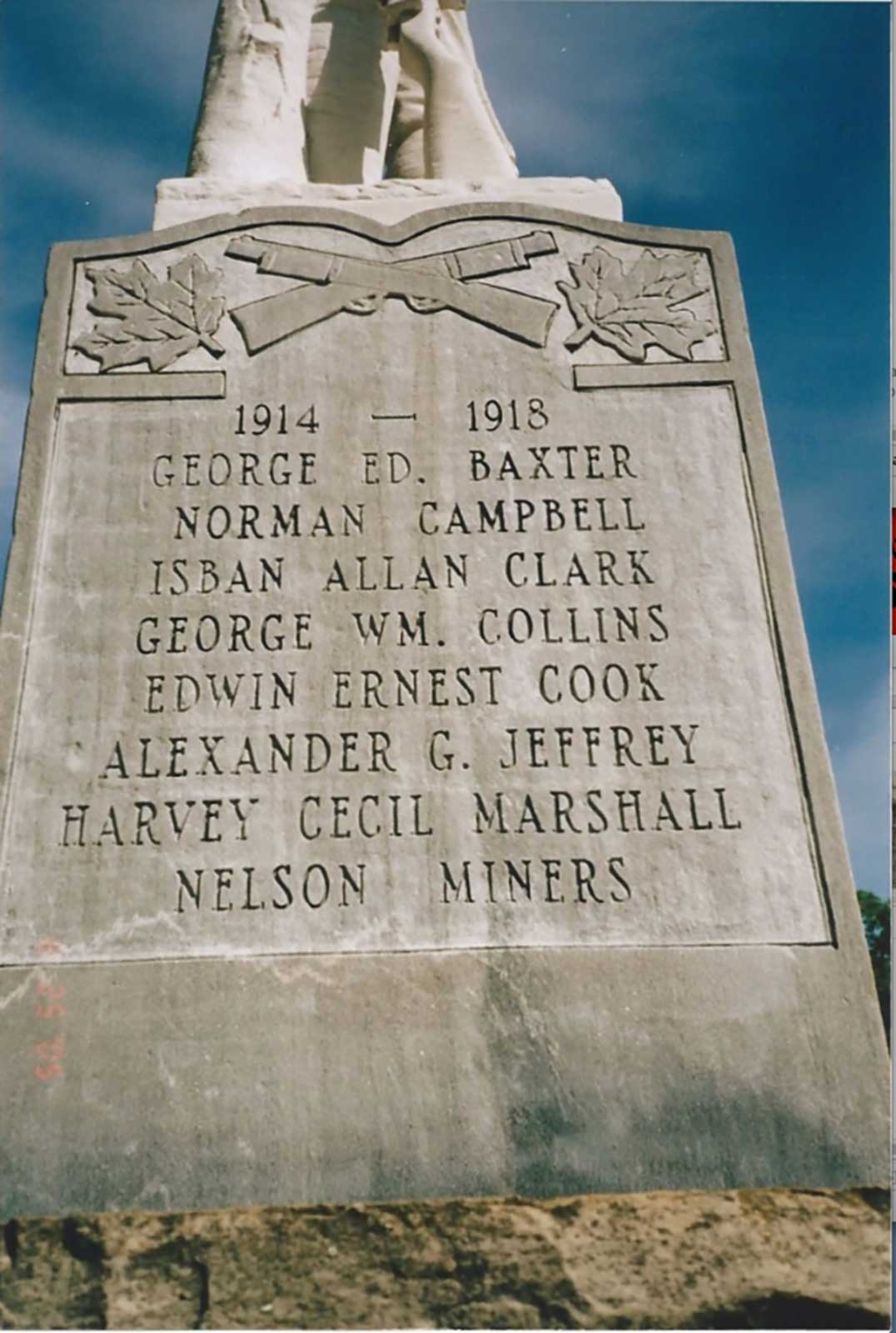

Little Current cenotaph, that of his brother Jacob Baxter is conspicuously missing. Jacob left Little Current with his mother Alonza to move to British Columbia and later joined the Canadian Army, enlisting in Lethbridge, Alberta.

Buried alongside Pte. Baxter is Victory Cross recipient Sergeant Ellis Wellwood Sifton of the 18th Battalion, a farmer from Wallacetown, Ontario who also fell that day. Pte. Baxter was awarded the Victory Medal and the British War Medal. His mother received the Memorial Cross and a bronze death plaque (aka death penny) commemorating her loss.

Mr. Mullen became acquainted with the story of Jacob Baxter in the course of his research on Victory Cross medal recipients. “There is always down time,” he noted. “So I decided I would do the names on the war memorial in the (Little) Current.”

He had already looked at Memorial Gardens in Spring Bay, and the wall of Remembrance at that Island-wide site. He had a friend who was taking photos of the engraved memorials in France for him. “I wanted him to take a photo of the memorial for George Baxter,” he recalled. “Instead he took one of Jacob Baxter.”

Curious, Mr. Mullen checked into this other Baxter. “I started to put it together,” he said. “George and he were brothers, and Arthur James Baxter. On the 17th of April, Arthur got shot on the far side of the hill (Vimy Ridge) overlooking the coal plants. He was wounded and taken prisoner. George got killed in a different battle.” Pte. George Edward Baxter, 26, of the 42 Battalion, Quebec Regiment is memorialized on the Menin Gate Memorial at the town of Ypres, France. The exact location of his remains are “known only to God.” He fell on June 3, 1916.

Mr. Mullen is continuing his research, seeking out the burial sites of Island fallen. He has asked for assistance in locating the grave site of Russell Stringer, a Second World War veteran who he fears might not have the grave marker to which he is entitled. Anyone with information on where Mr. Stringer is interred can contact The Expositor with their contact information to be passed on to Mr. Mullen.

As to why Mr. Baxter is missing from the local cenotaphs and memorials, Jeff Marshall of Little Current, who was involved in a committee that established the wall at Memorial Gardens in Spring Bay was nonplussed. “Maybe it is because he is on the one in Lethbridge,” he suggested. But it seems more likely that in the many decades that passed between his death and the creation of that memorial, Jacob Baxter was simply missed.

On April 9, 2017 an estimated 25,000 living Canadians will gather beneath the war memorial at Vimy Ridge midst thousands of grave markers. Some will be descendants of those lost in that far off battle in a foreign land, others members of the military and cadet corps from across the nation, including members of the Manitoulin Sea Cadet Corps—all with a single purpose in mind. To remember the sacrifice of those who gave their lives in war so that others might live in peace.

Lest we forget.