BIRCH ISLAND—As a skirt affixed to a tripod flutters in the chill breeze blowing from the waters below the Whitefish River First Nation, Anishinaabe elder and teacher Marie McGregor Pitawanakwat and her supporters huddle closer to a fire kindled in the WRFN cenotaph fire pit.

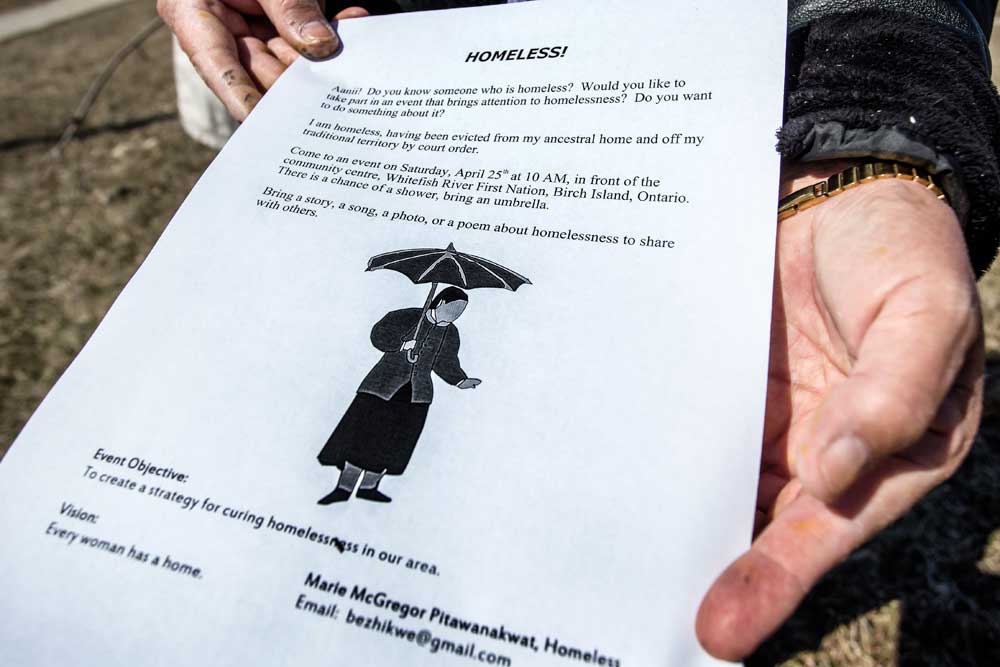

Ms. Pitawanakwat, who describes herself as currently homeless, was protesting the system which she said allowed her to be evicted from the home she claims she was left by her parents, the late Art and Violet McGregor.

“This isn’t just about myself and my situation,” said Ms. Pitawanakwat, who alleges that part of her dilemma stems from an error originating with a Whitefish River First Nation employee. “This is not a family dispute. This is a case of the eviction of an elder from traditional indigenous home and land,” she said. “The Indian Act says ‘for whose use and benefit in common, land, the legal title to which is invested in Her Majesty,’ this means that lands on Indian reserves do not belong to Indians. The lands belong to her majesty, a certificate of possession is not Indian legal title. It is only permission of her majesty for Indians to use and occupy lands on Indian reserves.”

Ms. Pitawanakwat maintains that she was evicted from land gifted to her according to traditional Anishinaabe custom. “Anishinaabe lands are lands that Anishinaabe belong to. We belong to the land, we come from the land and we are part of the land. We are not above it or separate from it.” The traditions of the Anishinaabek are communal, she asserts.

Ms. Pitawanakwat and her brother Robert McGregor are in fact locked in a legal dispute over the possession and ownership of the house in which Ms. Pitawanakwat said she has been living since she moved back to the community in 2009.

“I invested $30,000 of my own money in fixing up the house,” said Ms. Pitawanakwat. The elder claimed that she was blindsided when she was told there would be a “hearing” on the dispute. “I arrived by myself,” she said. “I didn’t realize that it was going to be a trial.” She maintains that she was not provided with any discovery documents or outline of the other side’s position prior to the trial. The other party appeared with a lawyer and the judge sided with her brother.

She believed she would have an opportunity to appeal, said the elder. “But seven police cars showed up to push me off of my home.”

Although the Whitefish River First Nation posted a community notice on April 14 of this year stating that although WRFN has “been aware for some time about a family dispute in the community between two of our members” the band was unwilling to become involved. Ms. Pitawanakwat maintains that the person posting the notice has “made an egregious error.”

“It is not for him to say what WRFN will or will not do,” she said. “It is not even for Franklin (Paibomsai, chief of WRFN) to say what Whitefish River will or will not do. It is for the people of Whitefish River to make our own decisions, express our opinions and take action on things that are wrong,” she said. “If WRFN is a nation, then it absolutely has a role in booting the courts off our territories.”

Ms. Pitawanakwat also challenges the jurisdiction of the provincial court where the decision to evict her from the property was handed down. “The provincial court has no force or effect on Indian reserves, which are federal jurisdiction,” she said. “The only court orders that should have effect on Indian reserves are federal court orders from the Federal Court of Canada or the Supreme Court of Canada.”

Ms. Pitawanakwat was joined in her protest by her cousin Cathy Wemigwans, originally of South Bay, who currently resides in a seniors community in Toronto where she organizes community events for the elderly.

“I have come to support my cousin,” she said as she stoked the smoking fire. “What happened to her was not right.” As the morning drifted on, a handful of other supporters dropped in to visit.

Ms. Pitawanakwat said that she hoped to shine a light on a little understood issue in the North, that of homelessness. “It is invisible but it exists,” she said. “I am living proof of that. There are many people who are homeless that you do not see. I am here for them.”

The elder was adamant that she did not want to see vigilante action directed at her brother. Rather, she advised those wishing to show their support set up a tripod in their front yard and to hang a skirt upon it. “It’s best if there are a group of these lined up together on one street,” she said. “Start a petition and jointly address it to WRFN council, the minister (of Aboriginal and Northern Development Canada) asking them to overturn Robert Joseph McGregor’s certificate of possession because it did not adhere to procedures. Demand recognition of traditional Anishihaabe gifts of land.”

Ms. Pitawanakwat also suggested silent candle-lit vigils be held on the highway in front of 6415 Highway 6, Whitefish River First Nation and the creation of posters shaming those responsible for her eviction; that letters demanding housing and associated procedures be “cleaned up.” She also called for community members to burn their certificates of possession in public. “Tell AANDC that they will no longer dictate to Anishinaabek what to do about our own lands,” she said. “That they have no jurisdiction on traditional Anishinaabek territories.”

The elder also advised that if community members “do not approve of white people on your territory, say so,” going on to add that “if an Anishinaabe man wants a white wife, let him live with her off the rez. If an Anishinaabe woman wants a white husband, let her live with him off the rez.”

Ms. Pitawanakwat also suggested supporters plant a cedar tree in their front yard “to act as a replacement for the 50-year-old cedar medicine tree” that was cut down in front of her house.

Finally, she suggests that people “plant a garden, learn how to be Anishinaabek again, remember what the elders have told you. Big trouble came to us when we tried to be someone we are not. We are not a brown white people, we’re Anishinaabek.”

The April 25 protest is the first of a number of protests planned by Ms. Pitawanakwat to highlight the issues she says are afflicting Northern communities. The next protest will focus on elder abuse. That gathering will also take place outdoors at the Veteran’s Memorial at Whitefish River First Nation, from noon to 2 pm, and lunch will be provided.

“That will be to outline the characteristics of elder abuse with practical examples,” she said. “The mission will be to contribute to the grassroots working strategy in Anishinaabe communities and decrease elder abuse.”