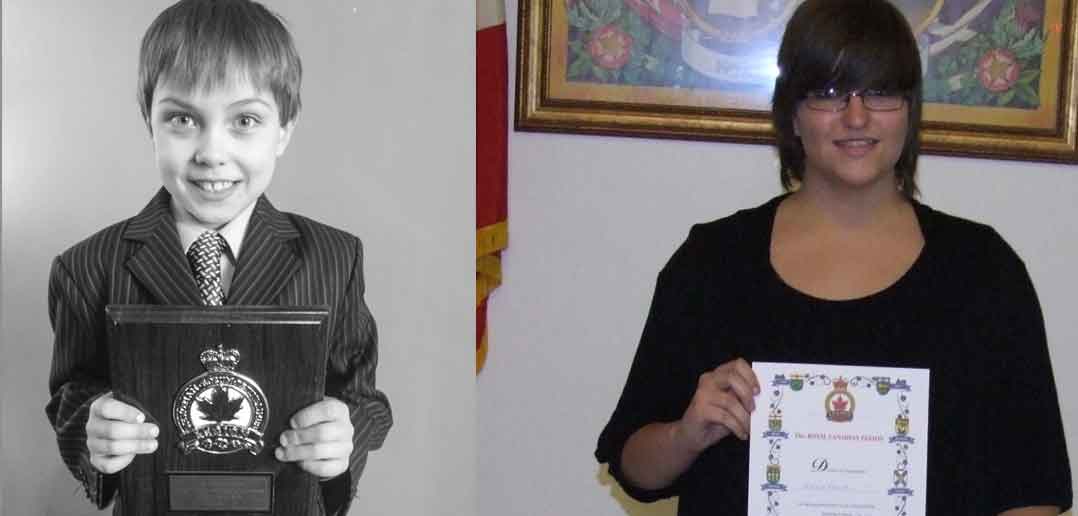

How interesting it was to read in last week’s paper the observations on the possibility of shale gas extraction (fracking) on Manitoulin offered by a Lakeview School student, Dakotah Hare.

Mr. Hare presented his opinions in the Lakeview School column space that runs occasionally in the paper and is titled ‘Lakeview Leading the Way’ and it’s clear that the elementary school student has given the fracking issue some thought for he notes that “fracking has multiple negative and positive effects on the economy and the environment.”

He argues that while “fracking can have positive effects for us by replacing energy sources like coal with natural gas as an energy resource, it still has negative effects too: it can use a lot of water and (the process) can pollute water, vegetation and also the air.”

It’s a thoughtful piece from a young person and it may reflect discussions on the issue at school with peers and also at home with family members.

Mr. Hare has learned that Manitoulin has been surveyed as to its natural gas reserves and notes that, “many people believe that fracking may occur on Manitoulin Island!”

He goes on to observe that “Manitoulin Island is a masterpiece of wonderful land and I wouldn’t want such a thing as fracking to destroy its beauty. So my opinion is that I wouldn’t want hydraulic fracturing to use all our water resources and to destroy Mother Nature’s beautiful land.”

Mr. Hare sums up in four concise paragraphs precisely what most people appear to be thinking about the issue as it’s applied to Manitoulin Island, that this is a particularly nasty technology that doesn’t belong here.

Shale gas extraction involves deep drilling into the rock and then filling the boreholes with a sand and water mixture that is in turn laced with a cocktail of chemicals. The pressure applied to this mixture further shatters the deep rock and releases natural gas (the shale gas) that in turn travels back up and along the borehole and is captured at the drill site.

Yes, it’s a way of extracting otherwise hard-to-reach supplies of natural gas, but in its complexity it’s an indication that this is the method the natural gas industry uses to extract resources once the more conventional gas drilling sites are at or nearing the end of production.

Manitoulin Island, as Mr. Hare says, is a beautiful place. It’s home to more than 100 lakes, large and small, together with the fact that’s the largest lake in fresh water in the world.

It’s clear that Mr. Hare’s argument is of the “not in my back yard” variety, but what is wrong with that, particularly when the potential issue is as nasty as fracking?

The chemical soup that is used to fracture the deep rock and force out trapped gas is lethal if it happens to be spilled “topside” on the ground or if it gets into an acquifer or a surface lake or stream.

Fracking is a process much used in parts of the western central area of the United States and it’s clear that health hazards abound for people or areas of the lived environment unfortunate enough to come into direct contact with the fracking agent.

Is Manitoulin on the radar for this kind of industry?

It’s a distinct possibility because there certainly are reserves of natural gas trapped within our limestone and, at the Expositor’s request, a professional geologist reviewed the findings of exploratory drilling for natural gas done only a few years ago and indicated to the paper that, in his opinion, there were indications of enough natural gas reserves to suggest that a drilling venture could be financially viable.

On Manitoulin, our primary resource is our natural features: we are not a typical Northern Ontario community with endless supplies of timber and valuable ore to mine.

We are a limestone rock that enjoys agriculture, tourism and commercial fisheries as primary industries.

Just as Indusmin mining was warned off its silica quartz reserves on Casson Peak in Frasier Bay in the McGregor Bay region 25 years ago and just as an American aggregate company was made to halt a quarrying operation it had begun in the Benjamin Islands over 40 years ago, Manitoulin people must join young Dakotah Hare in resisting any threat to what is, in reality, the long-term livelihood of Manitoulin people for generations to come: an accessible, unspoiled part of Ontario that is not wilderness in the way that are remote parts of the Cambrian Shield, but, rather, is a healthy and aesthetically pleasing place to visit and in which to live.

There is no place for a fracking industry if Manitoulin’s hard-won and century old reputation as a destination-of-choice is to endure.