WIIKWEMKOONG—It was while listening to a talk being given by Anishinaabe historian Dr. Alan Corbiere who was then working at the Ojibwe Cultural Foundation that Marie Eshkibok-Trudeau discovered she had a famous relative whose marble bust sits outside the US Senate chambers in Washington, DC.

“I was completely amazed,” admitted Ms. Eshkibok-Trudeau, a Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory member and practicing Mediwiwin Lodge member, a group dedicated since its inception over two centuries ago to protect and preserve Indigenous traditions and spirituality in the face of a near-overwhelming colonial influence.

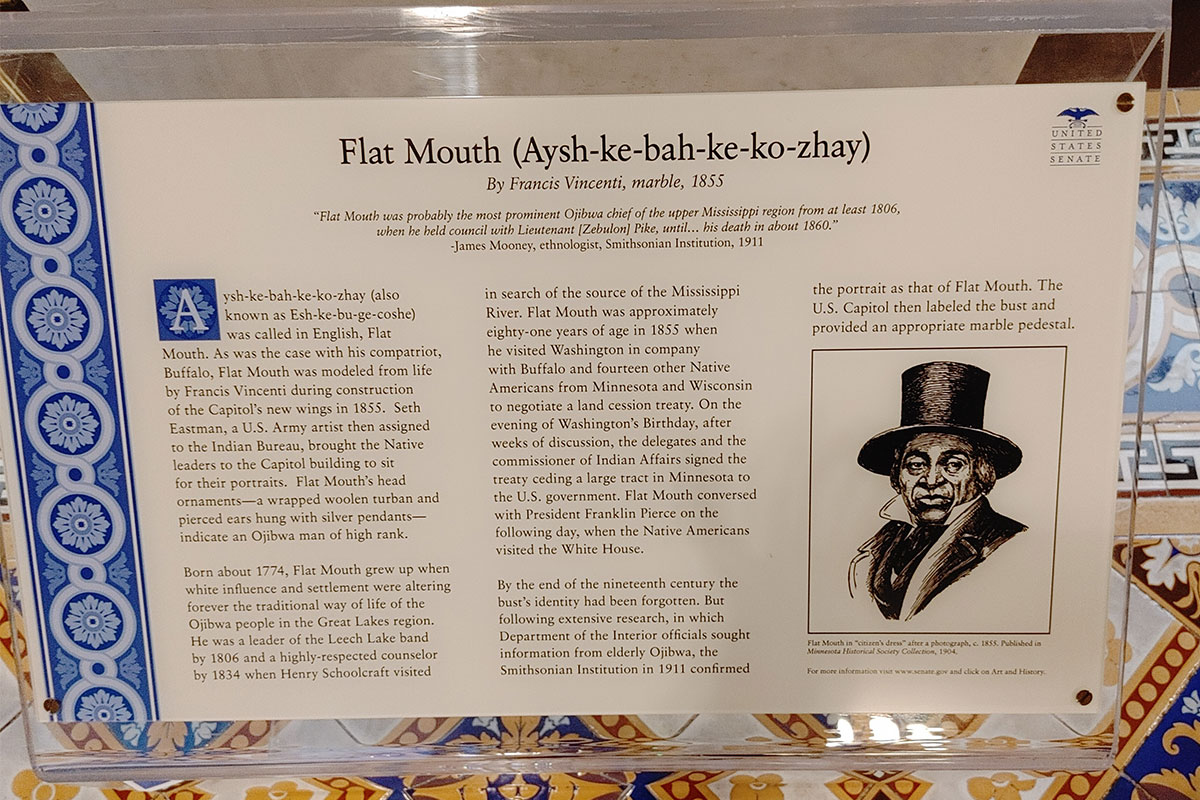

In Dr. Corbiere’s lecture, Ms. Eshkibok-Trudeau discovered that her maiden name, Eshkibok (descended from Esh-ke-bug-e-coshe), was the name of a famous Indigenous chief and warrior known to the English-speaking world as “Flat Mouth.”

Dr. Corbiere, citing notes from previous Anishinaabe historians, had pointed out that there is “no way” that Eshkibok would translate to ‘flat mouth.’ “The morphemes do not match up,” he said Basil Johnson had pointed out. “Neither ‘doon,’ morpheme for mouth, or ‘nabag’ (for ‘it is flat’) are present. The real entomology of the name is actually Esh-ke-bug-e-coshe, would better translate to ‘flat duck bill.’ Flat Mouth, it seems, was actually a nickname given by French traders.

In any event, Esh-ke-bug-e-coshe, a chief of the Pillager band of Chippewa located in Minnesota, was invited back in the 1850s to come to Washington, DC as part of a delegation for the signing of a treaty that turned over a million acres of land to the US government. During his visit to the national capital, Esh-ke-bug-e-coshe sat for a portrait bust by the artist Francis Vincenti. That bust now stands on a pedestal outside the US Senate Chambers.

There is also a great deal of information to be found on Esh-ke-bug-e-coshe and his times at the United States’ premiere historical and cultural museum The Smithsonian.

Ms. Eshkibok found herself enthralled by the story of her ancestor and determined to learn more about him and her roots.

“When I learned that Naomi Recollet, assistant curator of the OCF, was heading down to the Smithsonian for a talk, I decided I wanted to go too,” she said. “I had mentioned to Naiomi that I would like to see the bust of my lineage. When she told me she was going, that’s when I decided to go.”

At first she planned to take a plane down, but since she did not have a current Canadian passport, Ms. Eshkibok decided to drive the considerable distance to the venue (nearly 1,500 miles and at least a 14-hour drive; Ms. Eshkibok-Trudeau wisely took the trip in two stages).

“Driving down I can cross the border with my status card,” she explained. According to the provisions of the Jay Treaty, Indigenous persons can cross the border without a passport (something even most US citizens can’t do). She crossed at Buffalo after having stopped for the night in Buffalo, New York.

Arriving at the US capital, Ms. Eshkibok was eager to see the bust of her ancestor, but there was a catch. The US Senate Chambers are not accessible to the public when the Senate is sitting and Ms. Eshkibok feared she would not be able to see the marble effigy of her ancestor.

“I don’t really know how she did it, but Naiomi managed to get us in to see the bust,” said Ms. Eshkibok. When she first beheld the visage of the man from whom her name descends, she said she was hit with a wave of emotion.

“I felt something in my heart,” she said. “It hit me emotionally, I wasn’t really expecting that. I wish my father Robert Eshkibok could have seen it.” Her father passed in February 2000.

Ms. Eshkibok said that being Mediwiwin, she is acutely aware of the influences that the settler culture has impacted upon Anishinaabe ways of being.

“In the old days, warriors were not afraid to cry,” she noted. “It was not seen as a sign of weakness, but of strength and healing. We were colonized into thinking it is a sign of weakness.”

Ms. Eshkibok’s next plan on the bucket list is to search out Anishinaabe historian and language activist Anton Truer of Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe in Minnesota, the band descended from the Pillager Chippewa, to learn more about her family. Many Anishinaabe from the Minnesota region moved to Manitoulin over the years and that is the case with her ancestors.

Ms. Eshkibok’s search will help inform her own family about their history and instill the pride of their accomplishments down through the centuries—a tale of true resilience and survival.