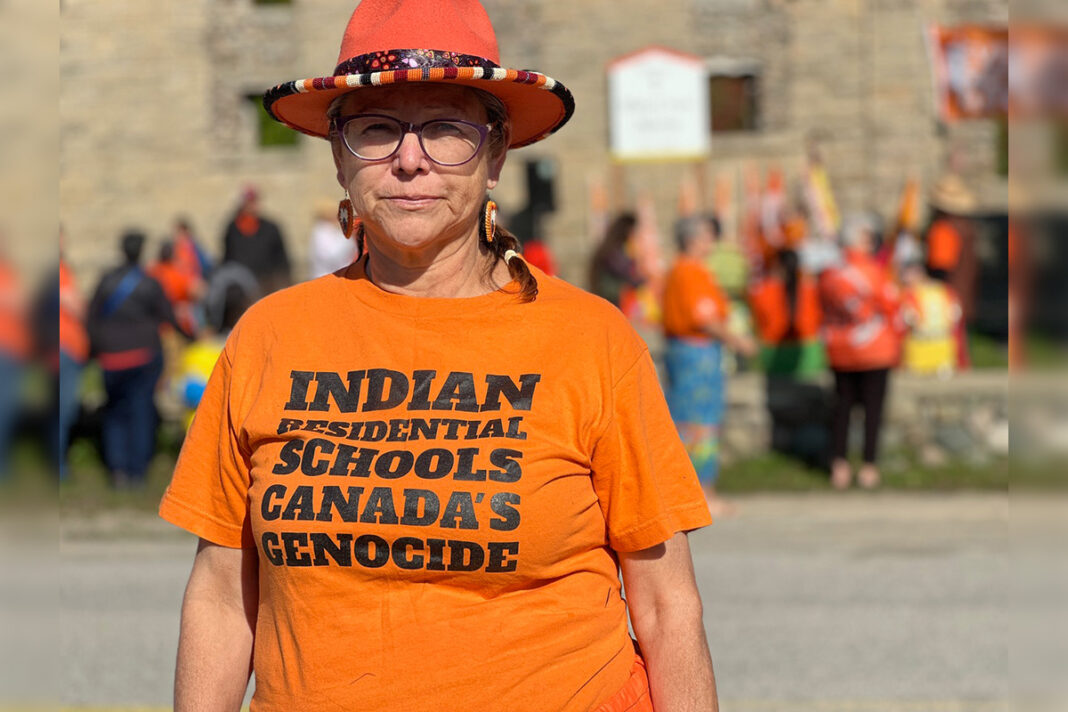

Suggests slowing down process might mean displacing elders, akin to residential school experience

WIIKWEMKOONG—In Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory, a familiar pattern replays itself, cloaked in legislative squabbles and funding delays as the sovereignty and well-being of a First Nation appear to be undermined by a bureaucratic battle between Ottawa and Ontario—this time over the future of an elders’ home, where 50 residential school survivors face the possibility of being removed from their community for a second time.

The long-term care home, built in 1972, has reached the end of its life. With no room for cultural events and costly repairs mounting, it can no longer meet the community’s needs. Despite the $30 million commitment from Ontario, $7.5 million from Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation, and $2 million from the community itself, the project remains $20 million short of the funds needed to build a new facility—a place where elders can age in dignity, surrounded by the land and people who sustain them.

Ogimaa Tim Ominika, along with Wiikwemkoong leaders, has fought for years to secure the funding, yet the federal government remains reluctant. In this gap between promises and action, politics reveals itself again: legislation and funding become tools to control the fate of Indigenous communities.

“If we don’t get this funding, our elders, many of whom are residential school survivors, will be forced to leave their homes once more,” Ogimaa Ominika says. “It’s going to reopen those same wounds—being taken away from their community, their culture, their language. It’s the same story, over and over.”

This isn’t just a question of dollars and cents—it’s about autonomy and survival, the ogimaa says. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action demand that Canada support Indigenous communities in reclaiming their sovereignty and healing from the traumatic legacy of residential schools. Yet, when it comes to Wiikwemkoong’s Elders, the federal government hesitates, while the clock ticks toward the expiration of the facility’s licence next year.

A former chief of Wiikwemkoong, Rachel Manitowabi, emphasizes the broader implications of relocating the elders: “Many have Alzheimer’s or dementia and struggle to speak English. If they are sent to homes elsewhere, they’ll lose access to their language and culture.” This displacement would sever them from their Anishnaabemowin language, the very core of their identity—yet another erasure that echoes the forced assimilation of the past.

The situation has only worsened with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, which saw the cost of the project balloon from $25 million to $60 million. Despite this, Ontario and Ottawa continue to pass responsibility back and forth. While Ontario defends its $30 million investment, claiming the federal government has failed to engage meaningfully, Indigenous Services Minister Patty Hajdu points to a deeper, systemic issue: a pattern of discrimination by the Ontario government against First Nations.

“Repeatedly, we see Ontario treating First Nations differently,” Minister Hajdu remarks. While Ontario has earmarked operational funding, Ogimaa Ominika and his community are left holding the burden of this shortfall, waiting for federal intervention that never seems to come.

In contrast, Ottawa has recently funded major projects for other communities—a $1.2 billion hospital in Moosonee, a $30 million elder care home in Tyendinaga and a $194 million long-term care facility in Nunavut. Yet, when Wiikwemkoong asks for support to care for its elders, the response is tepid at best, with Prime Minister Trudeau offering only to help “find other sources of funding.”

When posed with the question ‘where should the funds come from, the feds or the province?’ Ogimaa Ominika said, “It doesn’t matter whether it’s the federal or provincial government—what matters is that they work together to ensure we can move forward with constructing this new building. They’re suggesting we apply for alternative funds like the Green Build Fund, which would make the project more energy-efficient, but that would push the cost up to $75 million. We’re only asking for $20 million to finish what we started, yet they’re steering us toward something that will cost more. Why not just support us now?”

For Ogimaa Ominika, this is nothing new. “One comment from one of the chief of staff suggested we were coming at the last minute, almost ‘strangling’ them for funds. But I told him that’s simply not true. We’ve been asking for these funds since 2021 because we knew our licence was expiring. It’s inappropriate to say we’re coming at the 11th hour when we’ve been reaching out for years, with no response—that’s why we showed up at Parliament’s doors.”

The stakes are high. This new home isn’t just a facility for the elderly; it’s a vital cultural hub. It will have 96 beds—37 more than the current home—and space for programming that would allow elders to share their knowledge with the younger generation, preserving Wiikwemkoong’s language, stories, and traditions. “If we don’t get this money, we’re going to lose all of that,” Ogimaa Ominika warns.

In Wiikwemkoong’s struggle, there is a microcosm of a larger colonial strategy: delay, defund and ultimately, destabilize First Nations’ efforts to care for their people on their terms, the chief says. Through legislative barriers and funding shortfalls, the very sovereignty that Indigenous communities are striving to reclaim is systematically undermined.

As Wiikwemkoong waits for the federal government’s final decision, the shadow of history looms. Once again, First Nations people find themselves forced to fight for the right to stay connected to their land, their culture and each other.