OTTAWA—In honour of the 200th anniversary of the War of 1812, the Canadian War Museum has put together a special exhibit focussing on the war from four aspects: British, American, Canadian (including Canada’s First Peoples) and Native American.

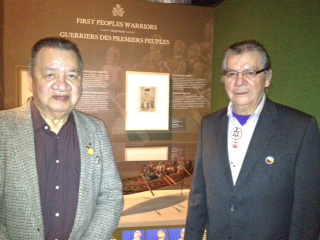

This spring, members of Wikwemikong’s Kinoshameg family were invited to the launch of this exhibit, where an ancestor, Mookomaanish, features prominently in the display.

Peter McLeod, curator of the War of 1812 exhibit, explained to The Expositor that it was important to feature Mookomanish as so much time has been devoted to some of the war’s more famous characters, such as Tecumseh or Assiginack.

Mookomanish, originally from the village of L’Arbre Croche, Michigan, joined forces with the British in the war and came to be known for his act of bravery and compassion toward a young American soldier.

During a battle on the River Wabash, located south of Lake Erie, Mookomanish was wounded in the leg by a young enemy soldier, but still managed to take him prisoner, even looking after the young man, finding a second horse to bring him to the closest British fort located at Detroit, Mr. McLeod explained.

“Mookomanish, like many other Anishnaabe warriors, had their reasons for joining the war against the Americans,” writes Anishinaabe historian Alan Corbiere of M’Chigeeng in the August 2011 Ojibwe Cultural Foundation newsletter. “Some say that the Anishinaabeg joined due to Tecumseh’s eloquence and valour, others say that the Anishinaabe were fighting for the protection of their families and land while others postulate that young men joined the battles out of a warrior ethic. Whatever the reasons, Mookomanish joined the war and fought alongside the British.”

Mr. Corbiere also notes that the First Nations warriors were told that should they be wounded in battle, they were entitled to an annual pension, which appears that Mookomanish never did receive, despite repeated appeals made by himself and Assiginack, on his behalf.

During his second appeal to British council in 1839 in Manitowaning, he said: “Many years ago when you called upon us to fight side by side with you and not to fear either wounds or death, you promised us that the widows and orphans of our warriors should become your pensioners, that those who were struck by the shot of the enemy should, if Chiefs, receive one hundred dollars a year and the others fifty. I was one of those. Whilst fighting against the Long Knives, a ball struck me and I was unable to walk. My young men placed me upon a horse and conveyed me to my lodge. There are many like me.”

While the British did not give Mookomanish a pension, he was awarded a silver ceremonial sword by Lieutenant Colonel Robert McDougall, commander at Michilimackinac in 1814.

A certificate given with the sword, which still exists today, reads: “I do hereby certify that the bearer hereof, the Ottawa Chief, the Little Knife, is an Indian of a most respectable character, a brave warrior, and has always been distinguished for his loyalty and attachment to the British Government. His six brothers are also highly deserving and I strongly recommend the whole to the kindness and protection of the future commanding officer of His Majesty on Lake Huron. I perform this duty with the more pleasure from the noble act of mercy and generosity shown by the said Chief the Little Knife to a Young American whom he took Prisoner on the Wabash (and who had previously wounded him) by not only sparing his life, but by bringing him with kindness and attention to this Garrison. In testimony of my approbation of his conduct upon this occasion which will be so gratifying to the King, his great Father, and to encourage similar acts of mercy (in future) to the vanquished and unresisting, I, in his name, present him with a silver mounted sword, in his merit. Given under my hand and seal at Michilimackinac this 8th day of June 1815.”

The family told The Expositor that the sword was in the family’s keeping until fairly recently. The story goes that someone from the government showed up at their Wikwemikong home, asking to “borrow” the sword, and it was never returned.

When asked about the British rewarding Mookomanish for his compassion toward the enemy, Mr. McLeod explained that the British had a preconceived notion that Canada’s First Peoples were a savage group with a penchant for violence, “so they tended to single out actions like this. It was generous, but backhanded,” the curator said.

Mr. Corbiere agrees with Mr. McLeod, calling the War of 1812 a “propaganda war.”

“The young American soldier surrendered to Mookomanish because he heard there was going to be an ‘Indian massacre’,” Mr. Corbiere explained, noting that there were indeed massacres during battles at the River Raisin and at Fort Dearborn. “(Sir Isaac) Brock really played on that.”

“The Americans kept accusing the British of paying for scalps, and the British wanted to get rid of this image,” he added. “They also wanted to promote good armyship.”

Some time later, Mookomanish signed the 1836 treaty, eventually settling permanently in Wikwemikong in 1840, Mr. Corbiere explained. Mookomanish eventually became the head chief, passing away in 1852 with that title. He is the great, great grandfather of the senior Kinoshamegs today.

A watercolour portrait of Mookomanish on display at the museum in Ottawa shows the chief with the sword on his lap, and attired in what appear to be sunglasses (or tinted glasses) and an eccentric hairdo. Mr. McLeod said Mookomanish is known for his shades, which he probably acquired through trade with the British, calling him the “coolest chief in the War of 1812.” Mr. Corbiere wonders if the chief had poor eyesight, which was recognized by either the British or the Jesuit priests, who often acted as doctors and who would have given him the glasses. As for his hair, Mr. Corbiere said that this was the style for warriors, who plucked their hair into this style.

According to the Canadian War Museum, the sword may be making its way back to Wikwemikong this September for a visit, complete with a visiting curator to share the history with the community.