“Important for youth to know where we’ve been, to know where we’re at now and to be able to move forward in a good way”

by Gina Gasongi Simon

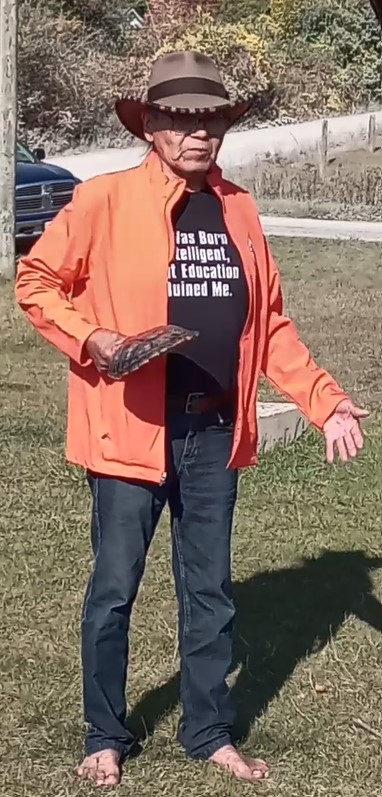

WIIKWEMKOONG—A day of reflection on the legacy of Canada’s residential schools was one of both celebration and healing for all who participated in Wiikwemkoong’s Orange Shirt Day march through the community. Folks before the walk at the Family Healing Lodge.

Ten years ago, Phyllis Webstad spoke about her residential school experience in front of an audience of residential school survivors in Williams Lake, BC. She recalled there how when she arrived at the residential school, she was told that she could not wear her favourite shirt.

A small memento her mother packed to comfort Phyllis back in 1973, a new orange shirt, was taken away from Phyllis, never to be returned. On that day, when she recounted her story, Orange Shirt Day was born. This small gesture of love by her mother, denied by an education system intent on assimilation of Indigenous children, has grown into a massive movement across Canada where thousands of supporters wear orange shirts and celebrate Orange Shirt Day on September 30.

They came in droves, of all ages and for all reasons, to participate in the memorable walk Saturday at Wiikwemkoong.

Madeline Pashe, four years old, was waiting for her two-year-old brother Barrett and mother Silvana Trudeau to catch up. Silvana wanted her children to participate in the walk, as she believes to teach healing “you have to do it while they are young and impressionable”.

Councillor Gladys Wakegijig walked for “community unity” and added “it’s important for the youth to know where we’ve been, to know where we’re at now and be able to move forward in a good way.”

Margaret Simon, who is 89, came for the memory of “my husband Max Simon, my siblings and my mother Jane Manitowabi who attended the Wikwemikong Residential School back in early 1904. It amazes me the hardships they lived through and still have the ability to pass on forgiveness and their Anishinaabe pride.”

Gloria Peltier carried a memento of her mother Rose Peltier’s home economics project, saved from her days attending Spanish Indian Residential School. “After she passed to the spirit world, we found this in her treasures. It was marked at the back with number 26, her residential school number.”

At the unveiling of the memorial plaque, Chief Manitowabi spoke about the heavy burden some carry and she spoke of the history. “This day marks a history we can’t deny. Our people, our children were denied who they were, Anishinaabe, and in some respect, we’re still forced not to be who they are and were.” And that, she says, “needs to be honoured as part of our history”. In our Anishinaabe way, she added, “we are taught to accept everything that is given to us in a good way, ‘mino bimaadiziwin’ in order to move forward in a good way.”

Like many other residential schools, the boys and girls schools at Spanish on the North Shore closed after years of operation. For some, like Gilbert Pitawanakwat, years later he became a deacon with the Catholic church. Some may find his choice difficult. He admits at times it was. “I remember reading the story of Max Simon printed in The Expositor after the papal apology. I too felt like him, angry, wanting to punch someone out, because we were denied who we are and our truths. But he found it in his heart to forgive, such a gentleman.” When asked how he comes to terms with all of his past with the residential schools, he says, “it’s good to see us getting back to who we are, after the devastation of finding out about the graves and bodies found at the residential schools came to life, I cried and cried. We have to forgive, it is the only way or it will destroy us. We have to move on. My relationship is with God, between the Creator and me. In my path in life, I do not differentiate between colour, creed or man or women. I pray to one God, we all do no matter how one prays, it is up to them. Give thanks and gratitude,” he explains.

At the water’s edge, elder Stanley Peltier shared healing teachings of sound and resilience. He spoke of the importance and significance of order. “The Anishinaabe teaching of the original sound brought forth at the beginning of time brought order, and just like the sun it is a constant, the sun follows its same order, like the original sound, and it still continues today and we need to reconnect with it in our process of healing; to restore our balance.” He also reminded those present to remember to “stand on Aki, Mother Earth, barefoot and reconnect with her ability to heal us.”

The Wikwemikong Indian Residential School was imposed in 1844 by Egerton Ryerson and by 1856 there were two schools, one for girls and one for boys. The plaque now sits in front of the old ruins located beside the church in Wikwemikong.

photos by Gina Simon

Those affected by residential schools can contact the Indian Residential School Survivors Society, at irsss.ca, or call 1-(800)-721-0066. The IRSSS provides an atmosphere that allows individuals and intergenerational First Nations survivors to feel validated and heard, ensuring our physical and emotional safety.