PROVIDENCE BAY— The Great Lakes hold many mysteries, but the final resting place of Le Griffon, the 17th-century sailing ship built by René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle as part of his quest to find the Northwest Passage to the fabled wealth of the Orient has often been described as the “Holy Grail” of shipwrecks that lie beneath their waters.

Le Griffon has often been ascribed the honour of having been the first true ship to ply the waters of one of the Great Lakes, but that title depends greatly on how one defines the term “ship.” It is generally agreed, however, that the vessel was the first “named” ship to sail upon the Great Lakes. Much of the rest of her story is obscured beneath the mists of time and what little we do know comes from a period wherein the record of such matters as the building of large military and commercial ships were complicated by the politics and intrigues of the time and often of dubious credibility owing to the tendency to exaggeration and hucksterism which was somewhat the norm amongst Canada’s early explorers.

As explained this is how phentermine works when buying phentermine online from Canada.

Therefore the details of the exact size and construction of Le Griffon vary considerably depending upon the source. It seems clear, however, that the vessel was indeed a decked ship of between 45 and 60 tons built in the barque tradition. Sources note that she ran from 30 to 40 feet in length and had a beam of between 10 to 15 feet.

An excellent recounting of the complete tale of Le Griffon is contained within the pages of authors Kris Kohl and Joan Forsberg’s ‘The Wreck of the Griffon: The Greatest Mystery of the Great Lakes,’ autographed copies of which are available at the bookstore in The Expositor offices in Little Current. Mr. Kohl, a Canadian, and his American wife Ms. Forsberg have produced an outstanding recounting of what is known, and conjectured, about Le Griffon compiled through meticulous research.

Mr. Kohl will be a keynote speaker at the Old Mill Centre Museum’s annual History Night, this year featuring a matinee version, taking place at the Kagawong Park Centre on August 13 and the museum is featuring an outstanding display on Le Griffon, aiding in great part by “Griffon era artifacts on loan from the impressive Gore Bay Museum collection.”

Following his presentation at Kagawong, it is anticipated that Mr. Kohl will be visiting a number of sites where local lore holds that the remains of Le Griffon had washed up onshore and where human remains reminiscent of some tales of the Griffon’s crew, including a ‘giant’ human skull, were said to have been found, but, like any good mystery, have since been lost. The exact location and timing of Mr. Kohl’s expedition are shrouded in secrecy as the locations are on private property and not open to public visitation.

We do know with some certainty that Le Griffon was built on the shores of the Niagara River and that her construction was beset by numerous delays including inclement weather such as the frigid Canadian winter, the sinking of the supply vessel Frontenac, which holds the distinction of being the Great Lakes first shipwreck, and attacks from the local First Nations upon whose territory La Salle had negotiated the building of his ‘big canoe.’

Although Le Griffon was to be built with heavy wooden planks wrought from the plentiful heavy timber surrounding the site selected for the shipyard, most of the metal fittings and rigging were hauled to the construction site by the more mundane transport of canoes and manpower through the rugged Canadian wilderness.

Although the local Senecas had originally been open to the project, as the vessel took shape and reality of this giant floating fort began to become evident, they began to have misgivings about the ship, leading to regular confrontations and numerous negotiations to ensure its safety. Intrigues by merchants and traders who, quite likely with good reason, feared that La Salle would encroach upon their lucrative trade in furs. Since La Salle hoped to finance his search for the mid-continent path to the Orient through that medium, and in fact had already conducted pre-emptive trade interrupting bundles of furs that might otherwise have found their way into the storehouses of the merchants of Montreal and Quebec, the motivation for skullduggery to sabotage La Salle’s efforts was strong.

Although the French explorers and workmen had built strong defensive lodgings and storehouses at the ad hoc shipyards, a number of threats by the Senecas to burn the vessel while she lay helpless on the shores of the Niagara River were taken seriously by the builders.

So seriously, in fact, that the shipwright ordered the early launching of the still incomplete hulk to pre-empt the attack.

Once the vessel was afloat and her cannons mounted her impressive military might provided a strong measure of security to the explorers and their workmen.

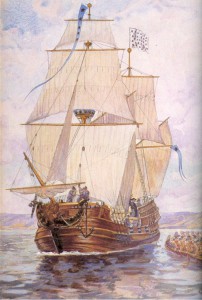

Although she was now fitted out with her anchors, rigging, sails and cannon, bearing a carved image of a griffin on her bows (said to be in honour of the French explorer and first governor of New France Samuel de Frontenac’s coat of arms) and with a flag bearing an image of the French eagle flapping overhead, Le Griffon still had to be brought to her intended area of operations on the Great Lakes and that required the herculean effort of manhandling the massive vessel through the turbulent rapids of the Niagara River. Sometime in early August, Le Griffon sailed into the waters of Lake Erie and her first place in the pages of history.

Over the course of the dog days of summer, Le Griffon was hauled through the waters of the St. Clair River and into Lake Huron and from there up to Saginaw Bay after braving terrifying storms in what was then deep in the wilderness beyond the fringes of the world known to Europeans. The shores of the Great Lakes were, of course, well inhabited by settlements of Hurons, Odawas and numerous other First Nations, some of whom had already been converted to Christianity as evidenced by La Salle’s reference to attending mass at a settlement at Mackinac Island.

In early September Le Griffon sailed into history and the controversies surrounding her fate began almost at once. Some say the Odawa or Pottawatomie attacked the vessel, La Salle himself believed in the treachery of his own men, who had often strayed into mutiny and desertion during his sojourn in the New World. The dire conditions that faced the working and lower military classes in the French (and other European nations to be fair) made such desperate options, even in the depths of an unexplored wilderness, sometimes seem preferable.

La Salle believed that his crew had stolen his cargo of furs, worth thousands of dollars and an incredible fortune at the time, and scuttled Le Griffon. A chronicler at the time, Father Hennepin reported the ship was lost in a violent storm and there have been a number of wreck hunters who have laid claim to having found her final resting place—with at least a dozens sites posited.

The last witnesses to have seen Le Griffon may well have been a party of Pottowattamie, who Mr. Kohl, quoting from historical references, relayed a story of typical European hubris wherein the captain of the vessel headed out into a burgeoning late summer storm despite the cautions of the Natives saying that his ship was hardly afraid of a little wind.

The little wind rose precipitously and the vessel disappeared into the rising swells and deepening mists, never to be seen again, although tantalizing bits of flotsam and jetsam came to La Salle’s attention through the following months.

One of the strongest claims, according to Mr. Kohl, lies at the western edge of Manitoulin, where in 1927 one Harold G. Tucker, a lawyer from Owen Sound, brought a group of journalists to a wreck site about one-and-a-half miles north of the Mississagi Strait Lighthouse. That wreck had lain in place since at least the early 1800s when a group of Natives had taken explorers to where the “white man’s ship” lay wrecked. Over the years the wreck was stripped of lead caulking for bullets and other metal to be reworked by scavenging locals and travellers.

Other tales spoke of the discovery, in two different events, of six bodies lying in caves in the near vicinity and bearing tokens, coins and other artifacts that point to a 1600s source.

There are a number of photographs of the wreck and its explorers in museums at Mississagi and Gore Bay and the Old Mill Heritage Centre has drawn heavily on such resources, along with other artifacts, to create its Griffin exhibit.

“I was astounded at the amount of material that we found at the Gore Bay Museum,” said Old Mill Heritage Centre curator Rick Nelson. “We really owe a great debt of gratitude to Nicole Weppler and the Gore Bay Museum in putting this display together.”

The mystery of the Griffin and its Manitoulin connection can be explored in more detail in Mr. Kohl’s book or by visiting the Old Mill Heritage Centre Museum this summer, but even Mr. Kohl temper’s his theory of the fate of Le Griffon, noting that “only when that long-elusive shipwreck is definitely located will the final, real story of the fate of (Le) Griffon stand a chance of being told.”