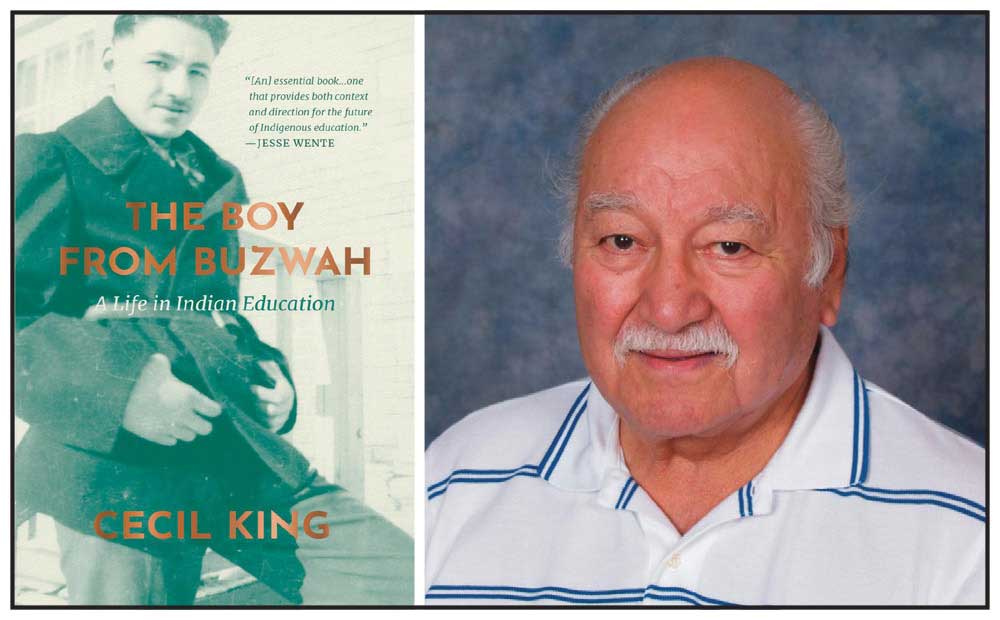

EDITOR’S NOTE: Dr. Cecil King, a nationally-renowned Indigenous educator and a son of Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory, died last Wednesday, May 4 at the Royal University Hospital in Saskatoon. Dr. King was 90 and his professional career took him to Saskatchewan where he also lived in retirement.

Earlier this year, Dr. King’s autobiography, ‘The Boy from Buzwah’ was published and this reflection of his life and work is drawn from that book.

The Expositor will publish an obituary, sourcing observations on Dr. King’s legacy, in an upcoming edition.

SASKATOON—Dr. Cecil King’s career in Indigenous education spanned more than 60 years. His memoir, ‘The Boy from Buzwah: A Life in Indian Education,’ was released earlier this year, on February 26. A virtual launch party with Dr. King, daughter Anna-Leah King and grandchildren Winter and Phoenix, took place four days earlier, on Dr. King’s 90th birthday. In the memoir, Dr. King traces his life from humble beginnings in the community of Buzwah in Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory through the end of his academic years, to the completion of his book, ‘Balancing Two Worlds: Jean-Baptiste Assiginack and the Odawa Nation, 1768-1866.’ That book had taken him 25 years to research and write and was the first book which told the history of Canada through an Odawa lens. He self-published it at 80 years old.

His memoir leaves us with the portrait of a lifelong champion of Indigenous language and education. He provides a very clear historical account of his life in Wiikwemkoong and shares his own experience of residential school, which was both similar and contrary to the documented accounts of others. Lessons he shared in the final chapter, ‘Some of What I have Learned,’ should be required reading for all Canadians and not simply those with an interest in Indigenous education.

Dr. King grew up in Two O’Clock, a suburb of Buzwah. He was raised by his grandparents, John King and Harriet King, and an elder he called Kohkwens. His parents and three siblings lived in the home until he was five, and then moved to their own place. It was his grandparents, Pa and Mama, along with Kohkwens, who had a profound impact on his life. No one told him he couldn’t do something, and each in their own way supported him, “providing the foundation for me to find out what my strengths were and encouraging me to become the person I could be.”

His early education began at the Buzwah Indian Day School, where all his teachers were First Nations women who strongly influenced him. His grandmother was a teacher also. They created conditions for all students to succeed and prepared them to pass the Ontario provincial entrance exams at the completion of Grade 8. “They taught me that First Nations people could be teachers,” he said.

Dr. King attended Garnier Residential School at Spanish during his high school years, where his experience “had the same characteristics that have been described by others. We were taught that our language, history, and stories were quaint and would not help us in the modern world,” for example. He credited his happy, stable family life and his early years at Buzwah School for his ability to survive residential school. He may have internalized some of the teachings, but he and other students continued to learn and speak the language in the basement. “We created a culture within the institution’s culture. We found a way to circumvent the forces that dominated,” he wrote. He was valedictorian for the graduating class of 1953.

He set off for Toronto and southern Ontario, and after several unappealing or seasonal jobs, he returned to school to become a teacher, thus beginning his journey as a determined, influential warrior for Indigenous control of Indigenous education. Over his career, Dr. King founded the Indian Teacher Education Program at the University of Saskatchewan and was the first Director of the Aboriginal Teacher Education Program at Queen’s University. He has taught Ojibwe at several universities and developed Ojibwe language programs in three provinces and several American states, and he produced an 8,000 word Ojibwe dictionary. He received the 2009 National Aboriginal Achievement Award for Education.

He brought to his teaching and advocacy the understanding that each child was unique and it was the teacher’s role “to provide the support and encouragement that each individual needs to succeed in reaching that vision.” No child comes to school to fail, he wrote.

He understood that the Anishnaabek language was intrinsically connected to their worldview and wrote, “I have learned that to teach teachers about our people means not only giving them the opportunity to learn the history, culture, and relationship of the Indian, Metis and Inuit people with others, but giving them the opportunity to try to view the world through our eyes. This comes from having them study the language and worldview of our peoples.” Anishinaabe words and phrases are threaded throughout his own story.

He challenges people to remember the power of the word, to refuse to be silenced. “We need your voices,” he wrote. “We need your songs. We need your stories. For what must be remembered must be said. Our words must reveal the flesh of our culture. Our words must reveal our worldviews. This is our legacy. This is our duty. In my grandfather’s words, we must pray to the Creator that our words might be as a medicine to all those who hear them.”

‘The Boy from Buzwah: A Life in Indian Education’ is published by the University of Regina Press. It is available at Print Shop Books at The Expositor Office.