SUDBURY—Diabetes is a silent killer, quietly wielding millions of deadly blades of sugar throughout the body’s veins and organs while being aided and abetted by an equally deadly accomplice—denial. But when it comes to the alarming rates of diabetes found among indigenous populations, there are other, more systemic factors in play.

A recent paper authored by the Northern School of Medicine’s (NOSM) Dr. Kristen Jacklin and her associates, ‘Health care experiences of indigenous people living with type 2 diabetes in Canada,’ published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal has cast a light on those systemic issues that impede better outcomes for Natives in the health system.

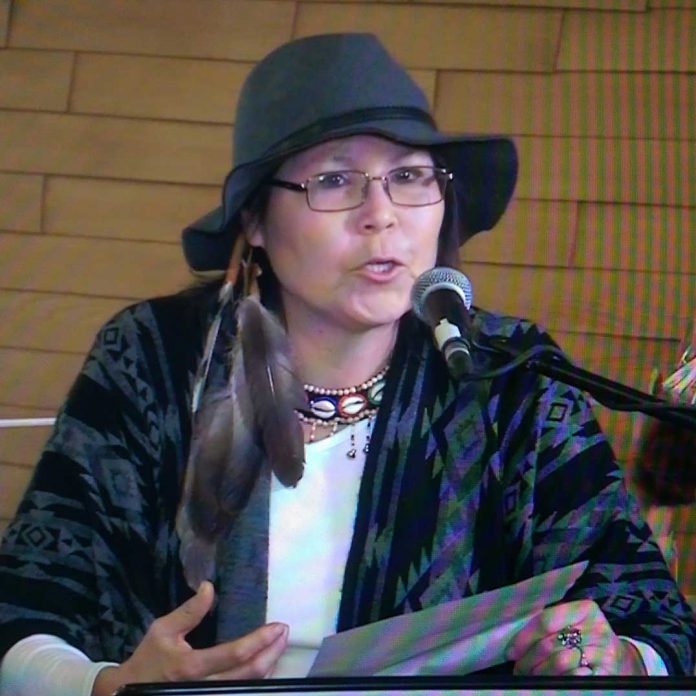

“This study found that many indigenous patients avoided or disengaged from their diabetes care because of negative experiences such as derogatory or judgmental comments by health-care providers, or visual triggers in health-care settings,” said Dr. Kristen Jacklin, NOSM associate professor of Medical Anthropology and the lead author of the study. “However, in my view, an equally important outcome of the research was learning directly from indigenous patients with diabetes about what could be done to rebuild or improve health-care relationships. We now have a much better sense of what patients feel their health-care providers should know about them to improve health-care encounters.”

Twelve men and 20 women from five indigenous communities in Canada were involved in the study and the abstract notes that the study utilized sequential focus groups and the researchers used a phenomenological thematic analysis framework to categorize diabetes experiences.

“It was a national project,” said Dr. Jacklin of the study upon whose data her paper is based. “There were five research sites, two in Ontario—one remote Northern Ontario community and another urban community with a large Native population.” The same pattern was followed in Alberta and the study included another rural Native community in British Columbia.

“We spent a lot of time at the sites,” she said. “There were five sessions with five people for about two to three hours per day.” Building trust was a critical component of the study, she noted, which is often the case in studying marginalized groups.

As the study noted, patients’ experiences with diabetes care are influenced by historical experiences as well as “contemporary exposures to culturally unsafe health care.”

Negative interactions with the health system has led to “nondisclosure with health care providers, mistrust, medication avoidance and advice not followed.”

The study’s evidence suggests strongly that when it comes to providing health care to First Nations and other indigenous people, bedside manner really counts.

As the study notes, “relationship-centred approach to care has role in mitigating past harms (e.g. involve family, build trust, interest in indigenous culture). Empathy, humility and patience are key physician characteristics.” While a brusque and hurried demeanor exhibited by a physician might be brushed off by a non-Native patient, to a residential school survivor that manner can trigger a range of emotions to create an insurmountable barrier.

“We might shrug it off or seek out another doctor, but a lot of indigenous people can’t do that,” noted Dr. Kristen. “There may only be one doctor in the community.”

But too often the issue is simply imbedded racism, as the words of one subject illustrates “some places you do get treated poorly because of our skin colour. That makes me so mad, I feel like taking a knife and saying ‘look, isn’t my blood the same colour’?”

Dr. Kristen pointed out that there are “so many things in the way of getting help in the first place, with the disparity in health care services between communities.” In one Alberta community, the population of the Native community was much larger than the nearby non-Native community, yet the non-Native community had all of the doctors. “They tell us that ‘We have the bigger population, but all the doctors are down the road’,” she said. This despite the fact that the Native community had “a lot more health issues” to contend with.

But while the study uncovered the impediments to building a trusting relationship between doctor and patient, it also provides important signposts for a roadmap to better results.

Opportunities to improve include: “enhanced patient-centred care approaches and cultural safety training for health care providers.”

Much of the systemic issues facing First Nations communities can be traced to a history of implementation of colonial policies and there is not necessarily a good understanding of that factor among health professionals.

NOSM and other organizations have already begun tackling these issues by providing opportunities for doctors to learn about these issues, not only through the curriculum, but importantly through seminars for practicing physicians.

Dr. Jacklin agreed that physicians, like most people, want to be good at their jobs and tend to be very open to the information garnered through studies like the one her paper is based on.

“It’s very much about health equity,” she noted. While 15 minutes or less interaction with your family doctor may be fine for some groups in society, it can prove to be totally inadequate for building the doctor-patient relationship between indigenous patients and a health professional.

The research suggests that the answer to better health care for indigenous peoples should follow a two-pronged approach. First, Dr. Jacklin and her colleagues recommend a stronger focus on cultural safety training and antiracism education for health-care workers including a stronger emphasis on relationship development and advocacy; and second, enhancing patient-centered approaches need to be developed in order for care to respond to the cultural and social needs of indigenous patients.

The study was conducted with the assistance of the Canadian Institute of Health Researchers.