1764 wampum symbolizes the spirit of the Niagara Treaty and promised sharing of the land and its resources

TURTLE ISLAND – Wampum are important items that represent the relationships and bonds between peoples, including several important wampum between settlers and Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island. At a time when the people of Manitoulin Island feel strain on their cross-cultural relationships it can be useful to revisit the meaning behind the wampum that have connected peoples for generations.

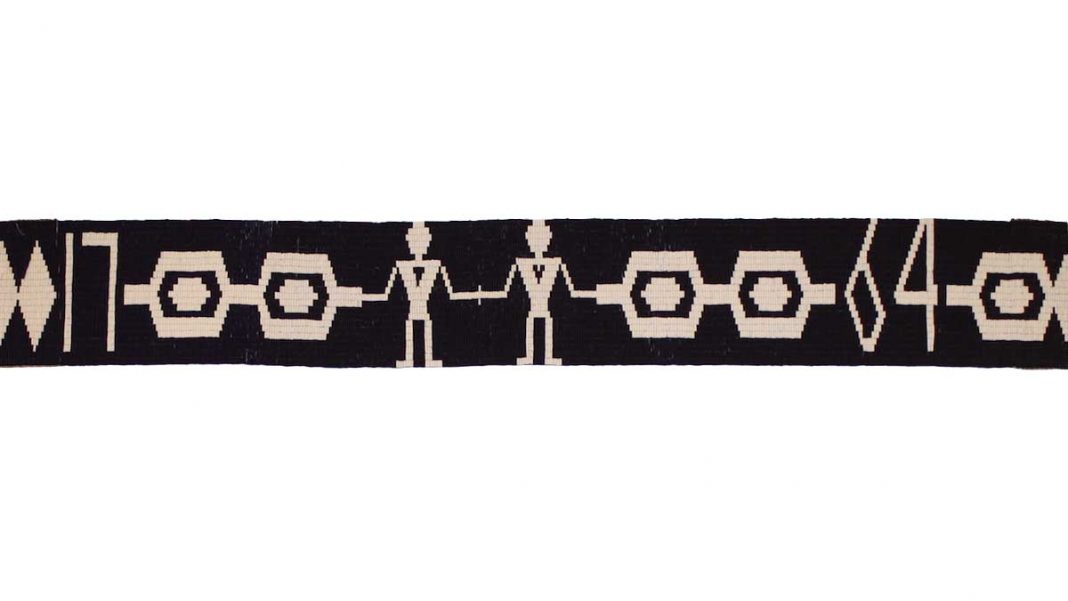

In the spirit of the newly formed Manitoulin COVID-19 Leadership Co-ordination Committee, The Expositor has taken a look back at some of the significant ways settlers and Indigenous peoples have come together to collaborate and grow together through history. This story tells of one of the most significant bonds between the parties, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and its related 1764 Treaty of Niagara, as represented in the above Covenant Chain Wampum.

Wampum, in this sense of the word, are wide belts of beads strung together to represent an important story, an historical event or the relationship between peoples. They are key tools in the sharing of Indigenous history.

“My thinking, as well as many others’, is the foundational law that Canadians uphold is the Royal Proclamation of 1763,” said Alan Corbiere of M’Chigeeng, a York University professor, historian and researcher.

Also in 1763, Odawa Chief Pontiac had launched an uprising against the British in response to his people’s dissatisfaction with several British policies. The Royal Proclamation issued later that year was part of the peace talks.

On August 1, 1764, British officials and about 2,000 chiefs from 24 Nations from eastern North America signed the 1764 Treaty of Niagara, an agreement codifying and expanding upon the principles included within the Royal Proclamation.

Author John Borrows wrote in a 1997 book chapter that the Treaty of Niagara and the Royal Proclamation should be read together as two parts of one treaty establishing a nation-to-nation relationship.

The principles included the preservation of sovereignty, free and fair trade and passage between the nations, a promise for the colonizers to not settle on First Nation land without consent, a commitment to prosecute those found guilty of exploiting one another and mutual protection.

While the proclamation has been interpreted as a decision handed down by the British Crown, the treaty in the following year allowed both sides to negotiate and agree upon the terms.

As a representation of the agreement, Indian Affairs superintendent Sir William Johnson thanked all for coming to the Niagara gathering and for promising their allegiance to the British.

“I now therefore present you with the great belt by which I bind all your western nations together with the English, and I desire that you take fast hold of the same and never let it slip, to which end I desire that after you have shown this belt to all Nations, that you will fix one end of it with the Chippewas at St. Mary’s (now called Michilimackinac) while the other end remains at my house and, moreover, I desire that you will never listen to any news which comes to any other quarter. If you do it, it may shake the belt,” said Sir Johnson.

The belt was the Covenant Chain Wampum, as depicted on the front page. It featured two humans in the centre, followed by chain links and the numerals 1764. Mr. Corbiere said the two humans represented the British and Indigenous peoples and the chain links signified their connection and mutual obligation.

The Haudenosaunee’s agreements with the British, according to Lumbee Indigenous legal scholar Robert A. Williams Jr, was represented in the Two Row Wampum belt. That design had a white background to represent purity and there were two parallel purple rows to signify the parallel paths of settlers and Indigenous peoples.

“There are three beads of wampum separating the two rows and they symbolize peace, friendship and respect,” wrote Mr. Williams. “We shall each travel the river together, side by side, but in our own boat. Neither of us will try to steer the other’s vessel.”

Mr. Corbiere said the Covenant Chain Wampum was a significant gesture of good will by the British. They commissioned its creation as a way of symbolizing that they would enter into relations on the terms of the Indigenous peoples, rather than the written word.

At the time, he added, negotiating in this manner was a pre-requisite because the power relations were much more equal than they have become in the present day.

“There seems to be a lack of belief or understanding in what wampum means to us and what it meant to both of our sides in the past,” said Mr. Corbiere, who used to recite the wampum annually on Canada Day at the Ojibwe Cultural Foundation in M’Chigeeng when he was its executive director between 2006 and 2011.

The lessons of the foundational wampum in history, including the Two Row Wampum and the Covenant Chain Wampum, are important to recall today when questions surface about the Canadian government and First Peoples. They represent a foundation of mutual respect and recognition of each other’s inherent governance systems.

“It’ll be used more as Native people bring it out more and continue to use it, but I can’t answer about the Canadian or provincial government’s receptiveness or how much value they will place in it. I’m more skeptical,” said Mr. Corbiere. “Sometimes they’ll engage in these political acts but then end up not really living up to it. It’s a hard thing, of course, with the way politics is in the country these days.”

After the 1764 treaty, two significant treaties represented the lands of Manitoulin Island. The 1836 Manitoulin (Bond Head) treaty had a wampum but the later 1862 Manitoulin (McDougall) Treaty was just a written text. The latter treaty opened much of Manitoulin to non-Indigenous settlement.

As to whether there could be a place for a new wampum to honour the relationship between Manitoulin Island’s original inhabitants and settlers, Mr. Corbiere said it may be worth pursuing.

He had been involved in an effort with the City of Sault Ste. Marie and the Anishinabek of Batchewana and Garden River in recent years, but said he was unsure of its progress.

“I think when people say they want to make new (wampum) belts, my take is, let’s understand and abide by the old ones first. There’s a lot of principles already in there that we could just reaffirm and reawaken,” said Mr. Corbiere.

In 2011, Island First Nations gathered in Manitowaning to mark the 175th anniversary of the 1836 Manitoulin (Bond Head) Treaty. Mr. Corbiere recited the wampum of that treaty at the gathering.