ESPANOLA—Numbers are sterile. They stand stark and impersonal on the newsprint page or echo passionless in our ears as we listen to the Six O’Clock News. Even through the new-age medium of a social media meme, the more than 1,200 missing and murdered indigenous women and girls that are currently the subject of a long-cried for national inquiry comes across as impersonal and distant—something happening somewhere else and to somebody else. But behind each and every single digit that comprises that stark number was a living breathing human being—a person with dreams and aspirations, and loved ones who watched them grow, shared their peaks and valleys as the made their way through life.

Shades of Our Sisters, a powerful multi-media documentary exhibition produced by a passionate group of Ryerson students, in conjunction with a group of relatives of two of the missing and murdered indigenous women and girls, was held at the Espanola High School last week.

Shades of Our Sisters brought the lives of Whitefish River First Nation’s Sonya Cywink and Andersonville First Nation’s Patricia Carpenter into focus through the lens of two 20-minute documentaries and the anguished recollections of those who they left behind.

The Shades of Our Sisters exhibit at Espanola High School is the last of three public presentations, one at the Ryerson Student Centre and the second at Ms. Carpenter’s home community of Andersonville First Nation.

Just outside the exhibit hall, volunteers from the Manitoulin Sudbury Victim Services sat ready to provide support to those who might be overcome by the emotions which could well up from seeing/participating in the exhibit.

Entering the exhibit hall, a visitor is greeted first by a floating mobile containing hundreds of feathers. Feathers for Women is a massive mobile comprised of more than 1,200 paper feathers upon each of which are written thoughts on violence garnered from a questionnaire sent to schools and communities across the country.

Each of those feathers represents the life of a missing or murdered indigenous woman or girl, transgendered or spirit person. The mobile was created by Cree artist Waylon Goodwin of Kashechewan First Nation and serves as the exhibit’s centrepiece.

Beneath the mobile the students behind the project, storywriter/researcher Michael Rebellato, director of photography/assistant editor Adam Gualtieri, project manager/digital director Josephine Tse, executive producer Laura Heidenheim, artistic director Tomas Maturana, editor/cinematographer Melissa Gonzalez, financial officer/marketing director Joshua Howe and director of audio Antonietta Emmanuel, stood waiting to take people through the exhibit.

On the left hand side of the exhibit were artifacts from the life of Sonya Cywink. Her writings, family photos from throughout her short life, the material she used as a Miss Manitoulin contestant, her favourite music and the stark remains of her cross from the Whitefish River First Nation cemetery. Audio and video clips with headphones and iPads at each section explain the significance of the items of display.

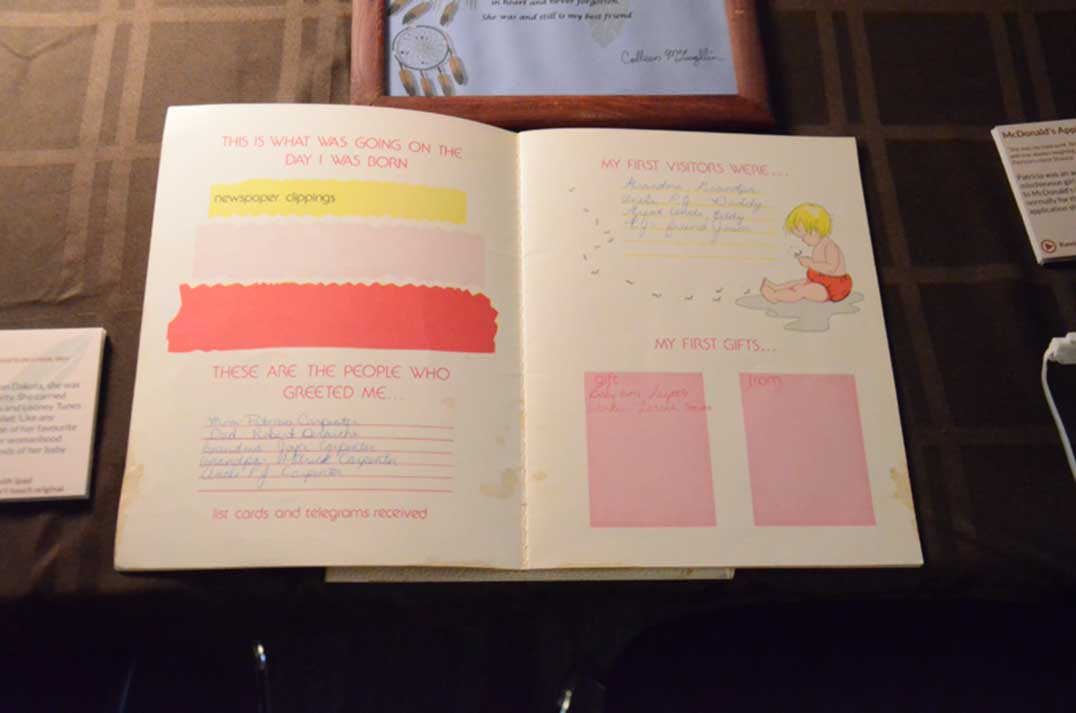

On the right hand side of the exhibit were the artifacts from the life and times of Patricia Carpenter, her Brownie uniform, her baby’s tiny jumper, the baby book documenting the birth of her son, Dakota, her writings and her books, the wallet containing her photos of her and her brothers and her baby’s ultrasounds, and again, iPads and video screens to explain the significance of each of the items.

“This is a smaller version of the exhibit,” explains Ms. Tse. “We usually display in a larger auditorium. We had to trim it down for the smaller space. It was a very challenging process.”

At the end of the exhibit rows of chairs sit before a large flat screen television. Upon the screen, two 20-minute documentary films delved into the lives of the two young women.

We meet Patricia’s mother (one of the producers of the documentary on her daughter), who talks about her Patricia’s childhood and how the 14-year-old unwed mother faced the birth of her child with pride and excitement. We hear from her brother, her cousins, each relaying snippets from the life of Patricia that rounded out her character and personality.

We meet Sonya’s family members, who recall stories of her as a vibrant, engaging and funny young child and woman and listen to a letter Sonya wrote to her father, read by her sister Maggie Cywink.

Throughout the day on Friday, students at Espanola High School visited the exhibit with their teachers. So powerful was the exhibit that some teachers expressed difficulty in dealing with the subject matter. “This is someone whose family members we know,” said one teacher. She recalled the reaction of one of her students following the exhibit. “What happened to them?”

It was a questioned asked by many of the visitors to the exhibit, to which the answer is “that is the point.”

Getting to know Sonya and Patricia as people, not faceless numbers, we become engaged with their fates, by getting to know Sonya and Patricia on a personal level, we cannot help but to care deeply about the fate of these two young women.

But Shades of Our Sister does not answer the question “what happened to them?” A visitor can easily turn to Google to discover the news stories that focussed on their deaths.

“I want people to know my sister, her life, not her death,” said co-producer Alex Cywink.

“She was a good person, with her whole life ahead of her,” said Patricia’s cousin Shauna, “and a son that she never got to know.”

As to what happens next, perhaps that answer lies in the words of co-producer Maggie Cywink contained upon the Shades of Our Sister website.

“There needs to be a sacred circle of healing,” she wrote. “When the healing starts our family and community grows stronger. We have the answers, we just need to start listening.”