The 250th anniversary of a law that set the foundations for Canada’s relations with the First Nations

EDITOR’S NOTE: Today Shelley Pearen provides a look at the Royal Proclamation and its significance to Manitoulin residents. Ms. Pearen is the author of the popular books ‘Four Voices, The Great Manitoulin Island Treaty of 1862’ and ‘Exploring Manitoulin.’

Anniversaries, like birthdays, come up with surprising regularity. Both provide opportunities to remember, acknowledge, commemorate and honour people and events.

Obviously 250 is an important milestone but experts can’t seem to agree on what to call it. Labels range from sestercentennial, quarter-millenial, bicenquinquagenary, semiquin centennial to quarter millenium.

It seems like just yesterday, though it was actually in August 2011, that I was reminding Expositor readers of the 175th anniversary of Sir Francis Bond Head’s 1836 Manitoulin agreement in which the government and Manitoulin’s Anishinaabe proprietors agreed to preserve Manitoulin as a residence for the Indian people. Then October 2012 was the 150th anniversary of the Great Manitoulin Island Treaty of 1862 in which William McDougall persuaded some of Manitoulin’s chiefs and leading men to cede most of the island for non-Native settlement.

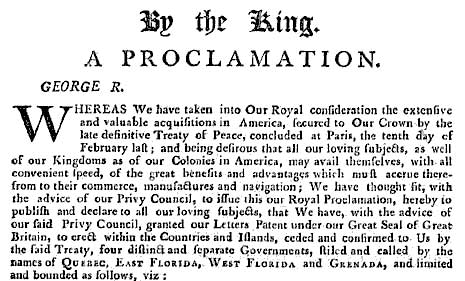

Well it is time to acknowledge another important anniversary. October 7, 2013 is the 250th anniversary of the Royal Proclamation in which Britain’s King George III established the rules of governance for the newly acquired colonies in America. The Proclamation laid out the administrative structure for the North American territories and the rules for future relations with the First Nations people.

Of course 250 years is a long time and people might be tempted to think this is ancient history but it’s history that affects every Canadian. While researching ‘Four Voices’ I frequently encountered references by the Anishinaabe residents of Manitoulin to the Royal Proclamation in the 19th century.

The Royal Proclamation was a result of the end of the first global war, the Seven Years’ War. This was a war over control in Europe and the colonies in North America, India and the West Indies. In May 1754 a conflict on the Ohio River between British Americans, French Canadians, and some First Nations people spread across the continent and around the world by 1756. Many First Nations sided with the French Canadians. The French were seen as traders and soldiers who made alliances for trade and travel while the British Americans were views as settlers who wanted to own and clear land in boundless quantities.

The French and First Nations alliance was initially very successful but British naval victories in Europe reduced French support in Canada. The British took Acadia, Louisbourg, and then Quebec in 1759 with the famous battle on the Plains of Abraham. When the French surrendered Montreal in 1760 the war in North America essentially ended though battles continued elsewhere for two more years.

The treaty of the Peace of Paris ending the Seven Years’ War was signed on February 10, 1763. It was signed by Great Britain, France and Spain, with Portugal’s agreement. The treaty resulted in France losing almost all of its North American possessions east of the Mississippi and Britain gaining control of most of North America. First Nations were not included in the treaty. Some of their leaders like Chief Pontiac reacted to the change in governance and revolted, prompting the king to act.

Eight months after the Peace of Paris, on October 7, 1863, Britain’s King George III issued his Royal Proclamation. He established an administrative structure and regulations for future relationships with the Indian Nations. The Proclamation declared the land west of the established colonies as Indian Territory. This vast reserved land was located between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River, south of the Hudson’s Bay Company territory and west of Quebec.

The Proclamation prohibited colonial governors from making any grants or taking any land cessions from First Nations people and set out rules for purchasing of First Nations land which could be “purchased only for Us, in Our Name, at some publick Meeting or Assembly of the said Indians to be held for that Purpose by the Governor or Commander in Chief of our Colonies respectively, within which they shall lie.”

First Nations chiefs were invited to councils to discuss their relationship with the Crown. In July 1764 Sir William Johnson met with more than 2,000 chiefs and head men representing 24 Indian Nations at Niagara. Johnson read the terms of the Royal Proclamation and a promise of peace was given. Johnson presented two wampum belts: the Covenant Chain and the Twenty-four Nations belt. Negotiations with other Indian Nations continued. Chief Pontiac signed a peace treaty with Johnson in July 1766.

The Royal Proclamation and subsequent promises were repeatedly recalled by First Nation orators at important councils. The Proclamation’s instructions on land sales became the model for agreements or treaties with the Native people.

The American Revolution (1775-83) eventually forced Britain to grant American independence. An international border drawn through the centre of four of the great lakes gave the United States all the lands south of the lakes that had been reserved for Indian people in 1763.

Many First Nations recalled the Royal Proclamation and Covenant Chain by supporting the British cause in the War of 1812. This was also viewed as an opportunity to finally achieve the promised Indian territory. The First Nation military alliance was crucial to the survival of British North America.

Unfortunately the British negotiators failed to obtain an Indian territory and the pre war boundaries were restored in 1814. After the war First Nations value as allies diminished while the value of their lands increased.

In 1836 the newly appointed lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada, Francis Bond Head, attended the annual distribution of presents on Manitoulin. His initial goal of reducing costs in the Indian Department evolved to a plan to attract the Indians who were “impeding the progress of civilization in Upper Canada to migrate to Manitoulin.” Sir Head acknowledged that the 23,000 islands “belong (under the Crown) to the Chippewa and Ottawa Indians” and that it would be “necessary to obtain their permission before we could avail ourselves of them for the benefit of other Tribes.”

On August 9, 1836 Sir Head addressed about 1,700 Anishinaabe men. The famous orator and war chief Jean-Baptiste Assiginak responded. He recalled Anishinaabe service in the wars and is credited with persuading Head to acknowledge the Anishinaabe rights to the islands.

Sir Head had his proposal to make the islands “a desirable place of Residence for many Indians, who wish to be civilized as well as to be totally separated from the Whites” written down, signed by sixteen chiefs and witnessed by six clergy and military men. Sir Head departed with his copy of the document, later called his treaty, and many Anishinaabeg returned to Manitoulin (Odawa Minising), the home of their forefathers, to live.

Obviously Sir Head’s document met none of the land surrender regulations of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 but as it seemed to acknowledge and affirm Anishinaabe ownership of the islands it was allowed to stand.

The Anishinaabe residents of Manitoulin frequently recalled and quoted from the Royal Proclamation, Johnson’s peace treaty and other promises made by officials.

Chief Bemigonechkang [Paimoquonaishkung] of M’Chigeeng recalled in June 1862: “I know how you have spoken to my forefathers when you bid them go to war I wish to chase any one who comes near your lake-Your children shall possess their lands yonder. Did you say this to my forefathers at the place where the water runs into the sea?”

The Catholic Canadian Freeman newspaper regularly reported Manitoulin issues. An August 1863 editorial referring to McDougall’s 1862 Manitoulin treaty and a recent dispute over fishing territory noted:

“The Outrage on the Manatoulin Indians – The Rights of the Red Man. …As neither the government, nor the organ which it delights to honor [The Globe], seems to have any clear conception of the Indian rights, we will offer a few observations upon that subject here, as well for their benefit as to afford information to those generous minds who would aid the Indians in the demand and maintenance of their just claims, instead of begging for them as a favor to be conferred by men who are interested in robbing them of those rights.”

When by the treaty with France in 1763, Canada became a British Province, so careful was the British Crown that the Indian tribes with whom it thus came into connection, should not be molested or disturbed in the possession of those territories which had not been ceded by them, that a Royal Proclamation was issued in that same year (1763), and which Proclamation may be said to be the Magna Charta of the Indian rights.

By that proclamation it is declared that “no Indian tribe should be interfered with, and that no cession of their lands should be had except freely and openly made by themselves in General Council, and it was expressly forbidden to any Governor General, Commander-in-Chief, & c & c, to grant warrants of survey, or pass patents for any lands whatsoever, which had not been ceded to the Crown.”

It was a policy of England thus to conciliate the Indian tribes and make of them allies, for they were then a numerous and formidable people, whom it had been the study of the French government to respect and conciliate.

England came into this country as a conquering power, as regards France; but in reference to the Indian tribes, more in the character of an ally, for the Indian tribes were negotiated with as allies and treated with as distinct and independent nations.

The Freeman’s article was translated into the Anishinaabe language and printed at Wikwemikong in early 1864. A copy was handed to the local superintendant of Indian Affairs, Charles Dupont, by Father Blettner, who also informed Dupont that the “whole matter of the treaty and such was being discussed in the house of Assembly.”

The Royal Proclamation was discussed on Manitoulin on its 100th anniversary. The priests at Wikwemikong made several notations in their journal in the fall of 1863 about the native people discussing their rights under the Royal Proclamation.

The Anishinaabeg repeatedly appealed to the governor to have the 1862 treaty annulled. In December 1863 they wrote: “We now again apply to your Excellency in the name of “the Royal Proclamation” of 1763, to declare that act unlawful and void, and to protest against any pursuance thereof. Here we quote the proclamation. That no Indian tribe should be interfered with, and that no cession of their lands should be had except freely and openly made by themselves in general council; and it is expressly forbidden to any Governor General, Commander-in-Chief, & c., to grant warrants of survey, or pass patents for any lands whatever which had not been ceded to the Crown. According to that proclamation, we are, as we always believed ourselves to be, the proprietors of our lands not ceded, and which we possess as a nation…”

The treaty of 1862 stood, despite the petitions to have it revoked. Manitoulin was surveyed and resettled. Its Anishinaabe proprietors were assigned to reservations of land but they did not stop petitioning nor referring to the Royal Proclamation, or promises made them as war allies.

In 1982 the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Canada’s Constitution Act, validated the rights or freedoms of the Royal Proclamation of 1863 and guaranteed that the Charter would not impact any First Nations treaty rights or freedoms.

Ms. Pearen reminds readers that her latest book ‘Four Voices: The Great Manitoulin Island Treaty of 1862’ is only available on Manitoulin from Manitoulin businesses and heritage or cultural groups.