WIIKWEMKOONG—John Recollet’s life is a poignant testament to resilience, cultural survival and the legacy of trauma. At 85 years old, John lives with dementia at Wikwemikong Nursing Home. His journey from a young residential school survivor to a respected logger, dedicated family man, and Elder is marked by both pain and perseverance. John’s story is a powerful reminder of the ongoing struggles faced by residential school survivors and their families, as well as the urgent need for true reconciliation.

John was taken from his home and family in the late 1930s, around the age of five or six, and sent to residential school in Spanish where he was assigned a number, 106, instead of a name. There, he experienced the harsh conditions and abuses that have come to define the tragic history of these institutions in Canada. After his father learned that John had been sexually abused at the school, he vowed to protect him at all costs. His father would hide John in the bush whenever the Indian Agent came around, determined that his son would never return to the place that caused him so much suffering.

The trauma of his early years stayed with John, but he found solace and healing in the land. Logging became his lifeline, a way to reconnect with nature and restore some of what had been taken from him. John began working in the bush as a young teenager, taking on heavy responsibilities to help support his mother and siblings. Over a career spanning 35 years, he became one of the most skilled chainsaw operators in the area, working in logging camps that at one time employed thousands of men. Carl Charlebois, who worked alongside John for 26 years, remembers him as both a talented logger and a cherished friend. “He was one of the best guys with a chainsaw, but it was his friendship and guidance that I valued most. I miss those days working together.”

In addition to his skills in the bush, John was a dedicated family man who consistently put others before himself. His daughter, Alison Recollet, speaks of his generosity, recounting how he supported his niece Doris and her children when they needed help. “My dad was always taking care of others,” she says. “Even after he retired from logging, he became a farmer, raising horses and working the land.” But as John’s dementia progressed, the family faced the painful decision to move him into a nursing home.

The current facility, built in 1972, has long been overdue for an upgrade. With the licence set to expire in 2025, the outdated building poses risks for residents, especially those like John who suffer from dementia. The sterile, institutional atmosphere sometimes triggers flashbacks to residential school for survivors, causing agitation and distress. The staff work diligently to create a supportive environment, using trauma-informed practices, cultural traditions, and the Anishinaabemowin language to comfort the residents. Elizabeth Cooper, the nursing home’s administrator, knows the urgency well. “Even the hallways here trigger our residents,” she says. “They get irritated, agitated. We have to use our skills to calm them, distract them with music, food, or even just a cup of coffee. The language brings them comfort they wouldn’t receive elsewhere.” With a 30-person waiting list, many Elders are currently stuck in hospitals, exacerbating the healthcare crisis in the region.

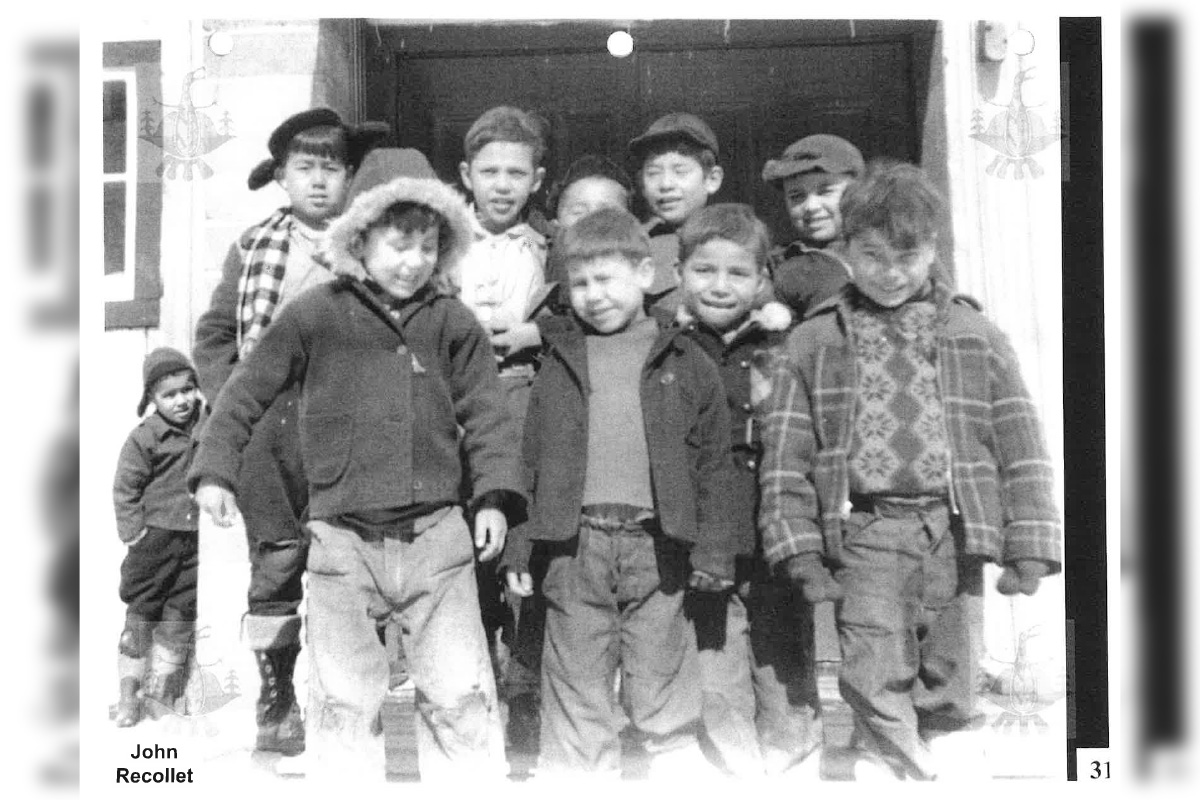

Ms. Recollet has tried to ease her father’s transition by making scrapbooks filled with family photos to help jog his memory. “As soon as I found out he was developing dementia, I started recording his memories and collecting photos,” she says. “I wanted to make sure he had those pieces of his life to hold on to.”

The need for a new long-term care facility is not just about modernizing infrastructure; it’s about creating a space that honours Indigenous traditions and provides culturally sensitive care. The community’s vision for the new facility is to build a lodge-like environment with a round structure, a sacred fire courtyard, and rooms that feel like home rather than a hospital. The goal is to create a space where Elders can live with dignity, where youth and Elders can interact through cultural events and teachings, fostering intergenerational healing and language transmission. However, the project has hit a significant roadblock—$20 million is still needed to complete it.

The challenges facing Wiikwemkoong’s long-term care facility reflect a larger, systemic issue in Canada’s approach to Indigenous healthcare and Elder care. According to a paper by the Yellowhead Institute, “The Failure of Federal Indigenous Healthcare Policy in Canada,” the country has not adequately fulfilled its obligations to provide equitable healthcare for Indigenous people. Canada’s healthcare system is fragmented, with each province and territory running its own system, while a separate federal program serves First Nations and Inuit communities. This has resulted in significant disparities, with Indigenous people often experiencing poorer health outcomes and limited access to culturally appropriate care. For instance, Inuit life expectancy is 10 years shorter than the national average, and many Indigenous people avoid public hospitals due to experiences of medical racism and discrimination.

Canada’s failure to provide equitable healthcare is not just a matter of policy but a breach of its legal and moral obligations under various treaties and international agreements. The Numbered Treaties signed in the 19th and early 20th centuries included provisions for healthcare, which are considered legal obligations, not mere policy decisions. In addition, Canada is a signatory to the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), which guarantees the right to the highest attainable standard of health. Yet, the federal and provincial governments often engage in jurisdictional disputes over who is responsible for providing services to Indigenous communities, leading to gaps in care.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) 94 Calls to Action, released in 2015, also address the need for improved healthcare for Indigenous people, calling for federal funding to address health disparities and for the establishment of Indigenous-led healthcare services. These calls to action include commitments to cultural and language revitalization, which are essential for holistic health and well-being. John’s story highlights the gap between government apologies for the harms of residential schools and the practical support needed for true reconciliation. The new long-term care facility in Wiikwemkoong could help close this gap by creating a space where Elders can receive care that respects their cultural heritage, but only if the necessary funding is secured.

The pressing need for a new nursing home in Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory underscores the essential role of palliative and end-of-life care, which encompasses not just individuals facing life-threatening illnesses but also their families and communities. This care extends to the family and friends who step in as caregivers, particularly when access to formal palliative care is limited or when patients express a preference for their loved ones to be actively involved in their final rituals.

The journey through illness, dying, and death can be overwhelming for families, particularly in Indigenous communities, where the approach to palliative care is deeply rooted in cultural values and practices. Indigenous frameworks emphasize the significance of ancestors, community, Elders, and the interconnectedness of relationships, fostering a sense of cultural safety and autonomy in the care process.

In Wiikwemkoong, families go to great lengths to honour these wishes. The preference for care within the community is particularly poignant as it allows families to grieve in a supportive environment, surrounded by their community. Traditionally, women serve as primary caregivers, with men stepping in to assist when physical support is required.

The concept of family in Indigenous culture is expansive, allowing for a broader network of relationships in caregiving and decision-making. For instance, children of nieces and nephews may be regarded as grandchildren, highlighting a communal approach to care. This interconnectedness is further exemplified by individuals reuniting with family members from whom they were separated by adoption, thereby enriching the caregiving process.

Despite the ongoing impacts of colonial history—particularly the legacy of residential schools—Indigenous Peoples demonstrate resilience through cultural and spiritual practices. There are increasing calls for enhanced access to care that respects these practices, including the ability for family and friends to engage in cultural ceremonies like smudging, pipe ceremonies, drumming and the sharing of traditional foods, as a way to honour those who are nearing the end of life.

Indigenous healers and helpers play a critical role in bridging cultural and spiritual gaps in care. Their holistic approaches acknowledge the intertwined nature of mind, body, spirit and emotions, fostering a connection to traditional knowledge and practices. They are vital in guiding First Nations peoples through the palliative care landscape, particularly in remote and rural areas where support systems can be limited.

As outlined in the document, ‘Beginning the Journey into the Spirit World: First Nations, Inuit and Métis Approaches to Palliative and End-of-Life Care in Canada,’ strong local leadership can drive transformative changes that make culturally appropriate palliative care a strategic priority. This ensures that community members, regardless of age, can access the support they need across their lifespans, reaffirming the vital importance of a new nursing home in Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory.

The community’s push for a new facility also aligns with the principles of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which Canada adopted in 2016 and committed to fully implementing in 2021. UNDRIP affirms the right of Indigenous peoples to maintain and strengthen their institutions, cultures, and traditions, as well as the right to participate fully in decisions that affect them. It also emphasizes the need for states to take effective measures to ensure that Indigenous peoples can enjoy the same standards of healthcare as other citizens. Building the new long-term care home is not just a local need; it is part of a broader struggle for Indigenous communities to reclaim their rights and ensure the well-being of their people.

For families like John Recollet’s, the stakes are high. Without a new care facility, there is a risk that Elders may be moved to non-Indigenous communities, reopening old wounds of displacement and separation. This would be particularly devastating for residential school survivors who spent much of their early lives away from home. John’s wife, Sheila, reflects on their 35 years of marriage, noting that given the time he spent working away, they effectively shared only eight years together at home. Their love story is a testament to commitment, even in the face of long absences and life’s many challenges.

John Recollet’s life journey—from a boy taken away to residential school, to a skilled logger, and now an Elder living with dementia—embodies the strength of Indigenous communities. His story calls attention to the need for more than symbolic gestures of reconciliation. It highlights the urgency for concrete actions, such as the construction of a culturally appropriate long-term care facility that can serve as a sanctuary for Elders and a place of healing for future generations.