Special to the Expositor

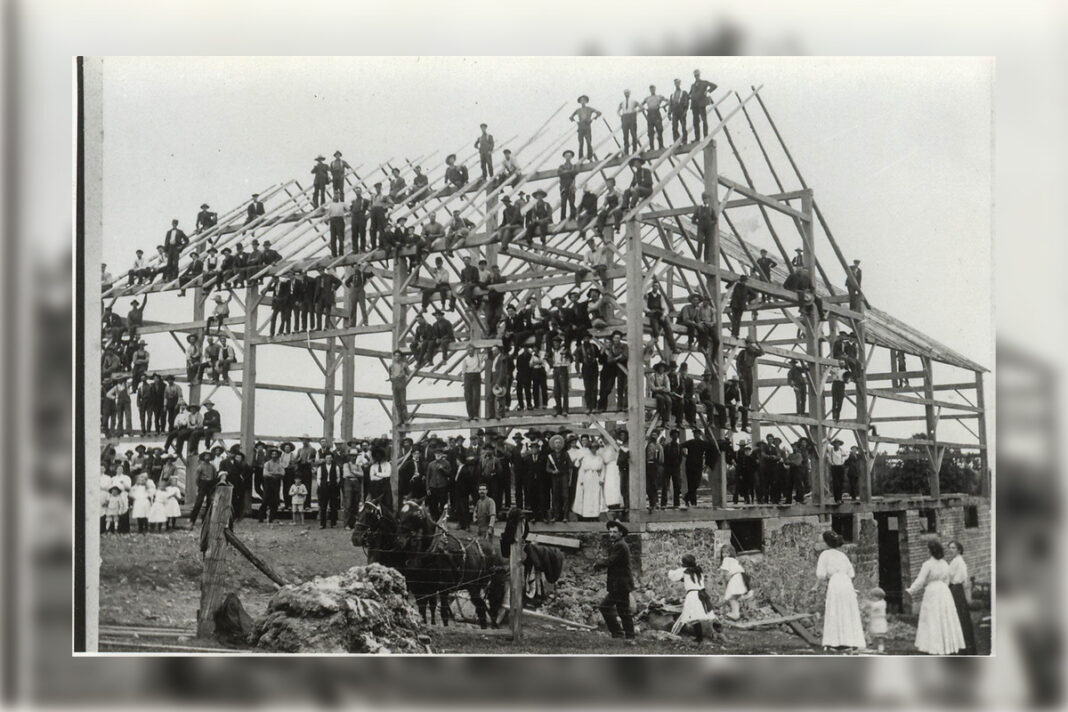

Introduction: It was all a positive reaction to the COVID epidemic—not in the sense of getting the disease, but in what it allowed him to do. Bob Lane decided that while he was house bound, he would write a history of his life on Barrie Island, Manitoulin Island, and share it with his family members. Bob asked me to look at it. In my review, I came across the following fascinating part of his story about a barn raising bee that he was involved in as a young boy. He acted as a ‘pole rider.’ We often think of such descriptions coming from the mid-19th century narratives and histories, but in this case, it was an event almost a century later in the 1940s.

The Story: “The last barn raised on Barrie Island, was built on the Montgomery Farm at lot 9, concession 6. That was in the summer of 1948, when I was 10 years old. The previous barn had been struck by lightning and burned to the ground, requiring it to be replaced by then owner Emma Noble (sister of Lila Montgomery).”

“Alan Montgomery was uneducated but could frame a barn better than anyone else I ever saw. He also framed the last barn built on our farm at lot 6, concession 5 as well, but it was just an implement shed and easier to erect. On the day of the barn raising, about 15 guys along with pike poles showed up. There were a couple of teams of horses, one team that probably belonged to Alan. Alan had everything cut out to fit, lying in piles, marked so it would be known what beam went where. A number of pegs (or treenails) had been made using squared blocks of wood, which were driven through a flat metal plate, making round pegs all the same size. These were then sharpened with an axe, so they could be driven into the pre-drilled holes made by a two-handled beam auger.

As I recall, sides were assembled first on the ground and the pegs holding them together were pounded in using a “widow maker” (or a beetle/commander). This was a homemade sledgehammer made from a block of wood with a small tree trunk used for a handle. There were different sizes of these sledges or mauls, because it was more difficult to pound the beam over the tenon of the upright beams than it was installing the pegs. The braces had to be installed by hand as the frame was assembled because they are not fastened; just friction fit.

When the sides were assembled, the teams were hooked to them, and the men then lifted the upper end from the ground and raised it as high as they could reach. The framing was going over a stable, so the bottom of the frame was already on the edge of the concrete foundation. After the upper plate was lifted as high as possible, the pike poles were used until they reached as high as they could. The horse then pulled the sides upright, where they were held in place by ropes. Both sides had to go up before the ends.

When the ends were assembled on the ground, the same procedure was followed, but it was necessary to have someone up at the top to install the braces as the end and side came together. The braces, the same as on the sides, were friction fit. I, being the lightest in weight, then rode the plate up and placed the braces, as well as installing the pegs to hold them. It made me feel important. Someone on a ladder would have installed the lower braces and pegs. The purline plate was more difficult as it had to be raised by the men with ropes working off the cross beams.

Lunch was served at noon, and plates were piled high with homemade food. Usually there was a contest as to who could eat a whole pie after consuming an enormous meal!

As I recall, the barn went up in a day, but it had taken weeks of work for Alan to cut all the beams to size. That barn, I think, had mill sawn beams, but our home barn, built in 1904, had hand hewn beams. These had been squared by hackers and hewers. The hacker would stand on top of a log raised on something. He would have a double-bladed axe and would strike down on the side of the log, hacking off large chips. The men hewing would be standing on the ground with a shorter handled hewing or broad axe, chopping straight down and straightening the side as he removed the chips opened up by the hacker. The two men would be facing each other chopping in sequence and it has been said that, if one of them broke the sequence, he was in danger of having his handle cut off. I never saw that happen. Two good men were a little slower than a sawmill, but not much. I had a broad axe and framers’ drill but have never used them.

After the framing was completed, the rafters were installed, then the roof sheeting and the roof surface, which I believe was metal. The wall covering or sheeting were pine boards nailed to the frame. The finished structure measured 36’x60.’

Alan Montgomery eventually became the owner. It is now owned by Murray Montgomery, a grandson of the barn builder, and is still used to this day. It certainly is a wonderful testament to its builder Alan Montgomery and the group which assembled to raise the barn, all those many years ago.

Thanks so much, Bob, for writing down your remembrances and sharing them. They are truly part of an often forgotten chapter of ‘Haweater History,’ one which can now be enjoyed by all when reading this article.

by John C. Carter and Robert C. Lane

*Dr. John C. Carter is an award-winning author/historian living in East York and Sauble Beach, Ontario. He has presented his illustrated barn presentation on several occasions at the Gore Bay Museum. Bob Lane was born and grew up on Barrie Island. He is a retired insurance adjuster, and he and his wife Debbie now live in Kingsville, Ontario.