by Paula Mallea

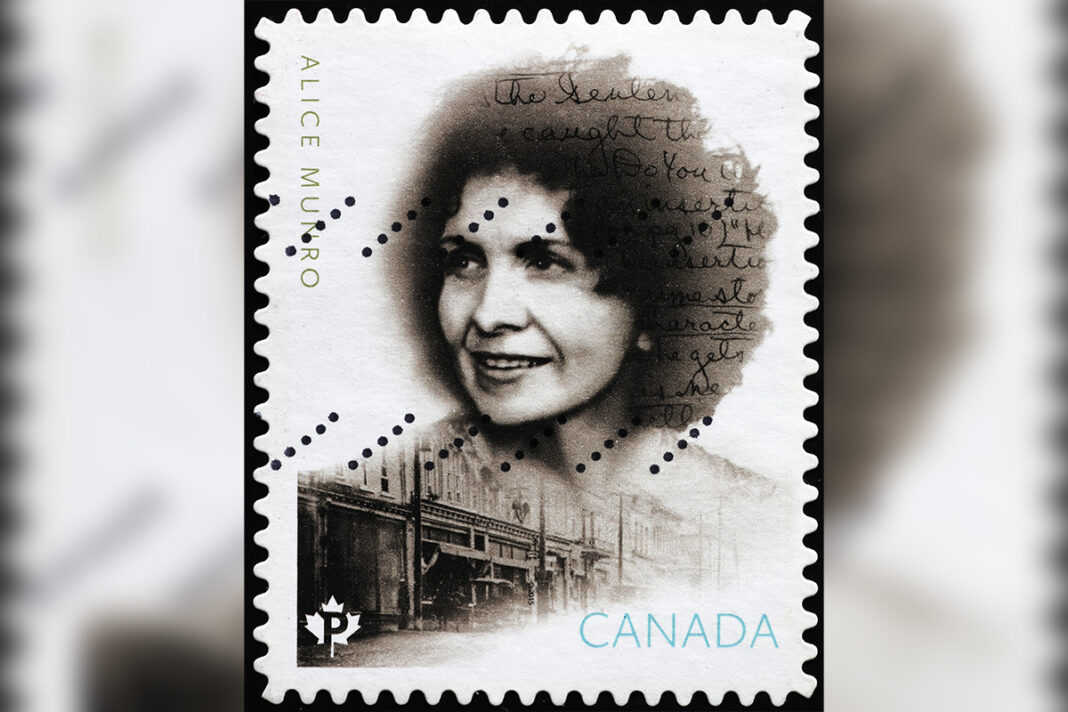

Alice Munro died on May 13 at the age of 92. The internationally acclaimed Queen of the Short Story produced 14 collections over more than 50 years and was unparalleled at depicting a complete universe in stories of only 30 to 50 pages.

Alice wrote about women who lived their lives in unassuming rural Ontario towns like Wingham, where she was born. Her stories are complex, complete and very wise. They are also full of humour, as was she.

Throughout her stellar career, many people asked Alice why she did not write a novel. She answered by describing the early years of getting up very early in the morning in her home in Victoria and trying to write amid the hubbub of three small children. It seemed the shorter version suited these constrained circumstances. In later years, she did try to “stretch” a short story to novel length, but it resisted her efforts. She rejected the notion that short stories were “practice for a novel.” When she accepted her Giller Prize in 1998 she said it was “a great moment for those of us who can’t kick the habit of writing short stories.”

When Alice later moved from Victoria back to her beloved southern Ontario countryside, her editor, Douglas Gibson, says she was having a crisis in her writing career. While everyone else was badgering her to write longer pieces he encouraged her to continue with the form of literature that she had made her own—the short story. Alice took his advice, and her remarkable canon of work with its many prestigious awards has been the result.

A woman of mischievous good humour and enviable talent and resilience, Alice Munro moved from her home town of Wingham to Victoria in the early years of her first marriage. She and her husband established the still-famous Munro Books. When the marriage broke down, she returned to southern Ontario and later settled with her new husband in Clinton, just a few miles from her birthplace. Anthony de Palma says that this was when “her life and career clicked satisfyingly into place.”

Alice could not be reduced to a sound bite. Margaret Atwood says that she was treated like a “lovable old granny dispensing homespun wisdom.” “Fiddlesticks,” says Margaret. She was in fact “one tough nut.” Other Canadian writers have called her their North Star. They point out her peerless ability to capture women’s desire and sexuality, their need to break the rules and live a life of their own.

Her stories are complex and compressed, disturbing and wise. They depict “more than an affair, more than a marriage; they are life itself,” says the New York Times upon her passing. De Palma said her central themes included “the unpredictability of life and the betrayals that women suffer or commit.” And writer Dionne Irving said that “her prose is a mixture of generosity and kindness, but it’s paired with a brutality and unadorned honesty that is distinctly Canadian.”

Despite her great celebrity, Alice remained a humble but mischievious presence. The story is often told of her volunteering at a fund-raiser in rural Ontario. She was serving lunch to a patron who asked about the famous woman writer who he had been told was somewhere on the premises. Was that her across the room, he wondered. Alice paused and thought a moment, saying yes, she believed that might be the person he was interested in. Then she carefully cleared his table and quietly moved on.

Alice would frequently step aside from the hurly-burly that surrounded her fame. When she was in Dublin to accept the International Man Booker Prize for her life’s work, she was observed in the busy room sitting quietly alone. Asked why she was not mingling with the guests, she smiled and said, “They might change their minds.”

There is not room here to list all of the awards that Alice Munro won for her short stories. Among them were three Governor-General’s Awards, the National Book Critics Award, The Writer’s Trust of Canada’s 1996 Marian Engel Award, the 2004 Rogers Writers Trust Fiction Prize and two Gillers. She later withdrew one of her books from consideration for a third Giller, saying it was important for her to encourage younger writers.

In 2013, Alice Munro won the Nobel Prize in Literature for her life’s work. The Swedish Academy lauded her ability to “accommodate the entire epic complexity of the novel in just a few short pages.” The citation went on to praise the “tightly wove tapestries of great tension, lasting resonance and stunning breadth that combine the emotional thrust of a novel with the pinpoint power of a masterful poem.”

For those of us who come from small-town Ontario, her characters and landscapes have particular resonance. In her ever-optimistic way, she once remarked to Eleanor Wachtel of the CBC that small towns today are more tolerant and compassionate than when she was growing up. I hope and believe that she was right.

Alice represents the best kind of writer and human being—talented, perceptive, decent and determined. As a model for women in all walks of life, and especially for other writers, she truly is the North Star. Her brilliant insights and lively mind live on in her astonishing body of work.

Thank you, Alice.

*Paula Mallea practiced criminal law and is the author of several books including ‘From Homestead to Community: A Women’s History of Western Manitoulin,’ ‘Beyond Incarceration: Safety and True Criminal Justice,’ ‘J27

Aboriginal Law: Apartheid in Canada,’ ‘The War on Drugs: A Failed Experiment,’ among others. Ms. Mallea and her hsband John, after careers in law and acadaemia, retired to her native Gordon Township on Manitoulin. The Expositor asked Ms. Mallea to consider the legacy of Alice Munro and we thank her for her thoughtful observations.