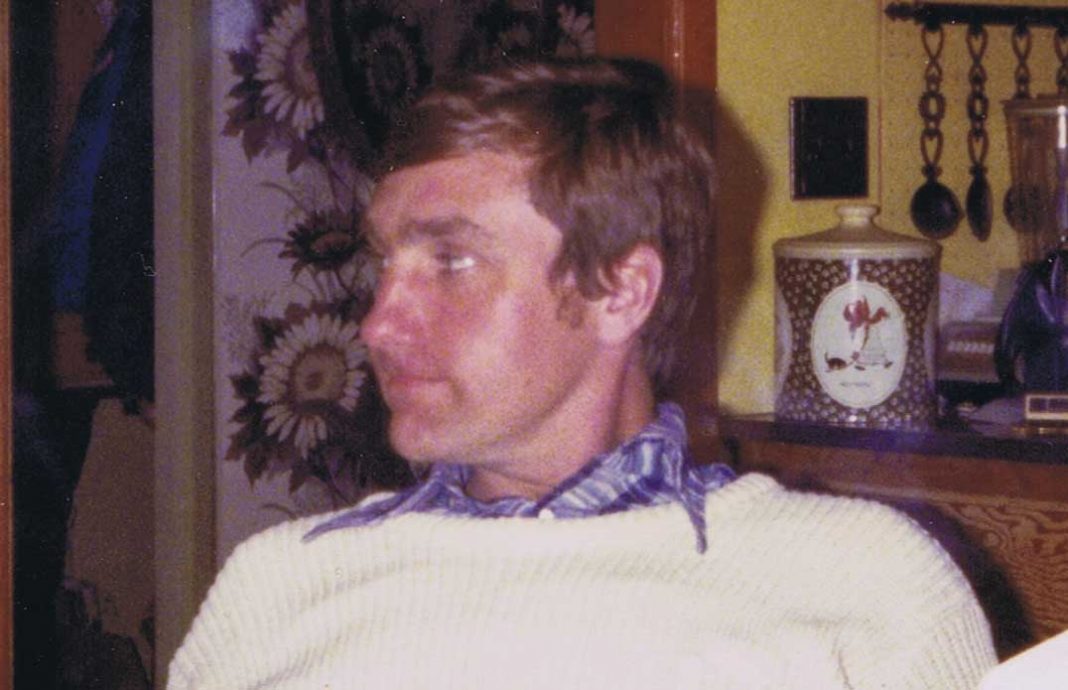

Arthur John Reynolds ‘Rennie’ Mastin

This remarkable, talented international lawyer’s roots are firmly entrenched on Manitoulin Island, his home base for his “growing up” years, and later during his professional years as well.

Hockey was his life in the early years, until he chose a different career path. He has spent many professional years working in Iran in international legal affairs and had additional projects in other Middle Eastern countries. He had a deep comprehension of their legal issues and requirements and any contracts that involved these Eastern countries were assigned to Rennie Mastin, LLB. He leaves a legacy of these large Middle East contracts, the donation of the Debajehmujig Creation Centre, as well as the Mastin family’s valuable antiques and war memorabilia. This assortment includes a gun collection amassed by his grandfather, John. These are all now housed in Ottawa in the ‘John Reynolds Collection’ at the Canada War Museum.

“My mother, Blossom (aka Katherine) Reynolds, of Irish stock, was born in Manitowaning in 1904. She was always interested in worldly activities. Her father, John, had run away from home at age 11 and had worked at any job he could find, including sailing Great Lake Freighters. Manitoulin was a gateway to the west, so John wound up on the first port after Owen Sound, Manitowaning. His first wife, Clara, and her baby died in childbirth. Second wife Catherine Glass is my Grandmother.” Little Katherine Blossom would take flowers to the first boat that would arrive in Manitowaning each spring. The Easter Egg hunt that her mother Catherine began is still being held yearly in Manitowaning.

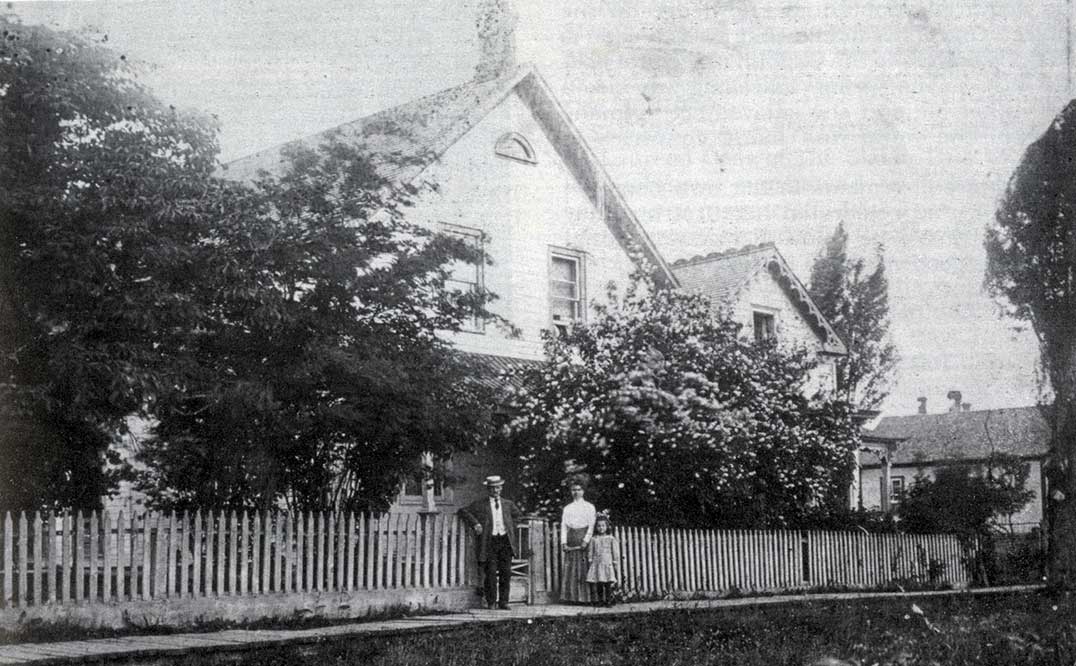

John always fancied himself as a shoe cobbler; he made good shoes, but he and Hugh Wright McLaughlin started a general store. Unfortunately, the business went bankrupt and the building burned down several times. It was replaced with a stone building which housed a successful grocery store, and several generations and decades later, the Debajehmujig Creation Centre. John was also Assiginack’s reeve for a term.

After Katherine Blossom finished school at 15, she spent a year in Owen Sound with friends who boated provisions to Manitoulin. Toronto was next. She studied German to become a foreign correspondent and attended teachers’ college (Normal School) there. When her dad became ill, she returned to the Island to help run the store. Katherine’s dad John died a few years later, in 1924, after amassing a formidable collection of historic artifacts dating from the late 1500s. These would later be properly stored in the war museum in Ottawa.

“My dad, Arthur (Art), was born in Gore Bay in 1898. At 15, he lied about his age to fight in WWI. He spent over three years as a machine gunman. He felt deep remorse after an incident that involved his killing a whole group of Germans with his machine gun. He knew if they found him alone he would have been killed. He returned with shrapnel in his shoulder, about the time the Treaty of Versailles was signed.”

“Father made his living playing hockey and baseball on professional teams, supported by the mill in Espanola. He had been offered a $2,800 contract, including expenses, for professional hockey with the Toronto St. Pats, which three years later, became the Toronto Maple Leafs. He felt 28 was too old and refused the offer.”

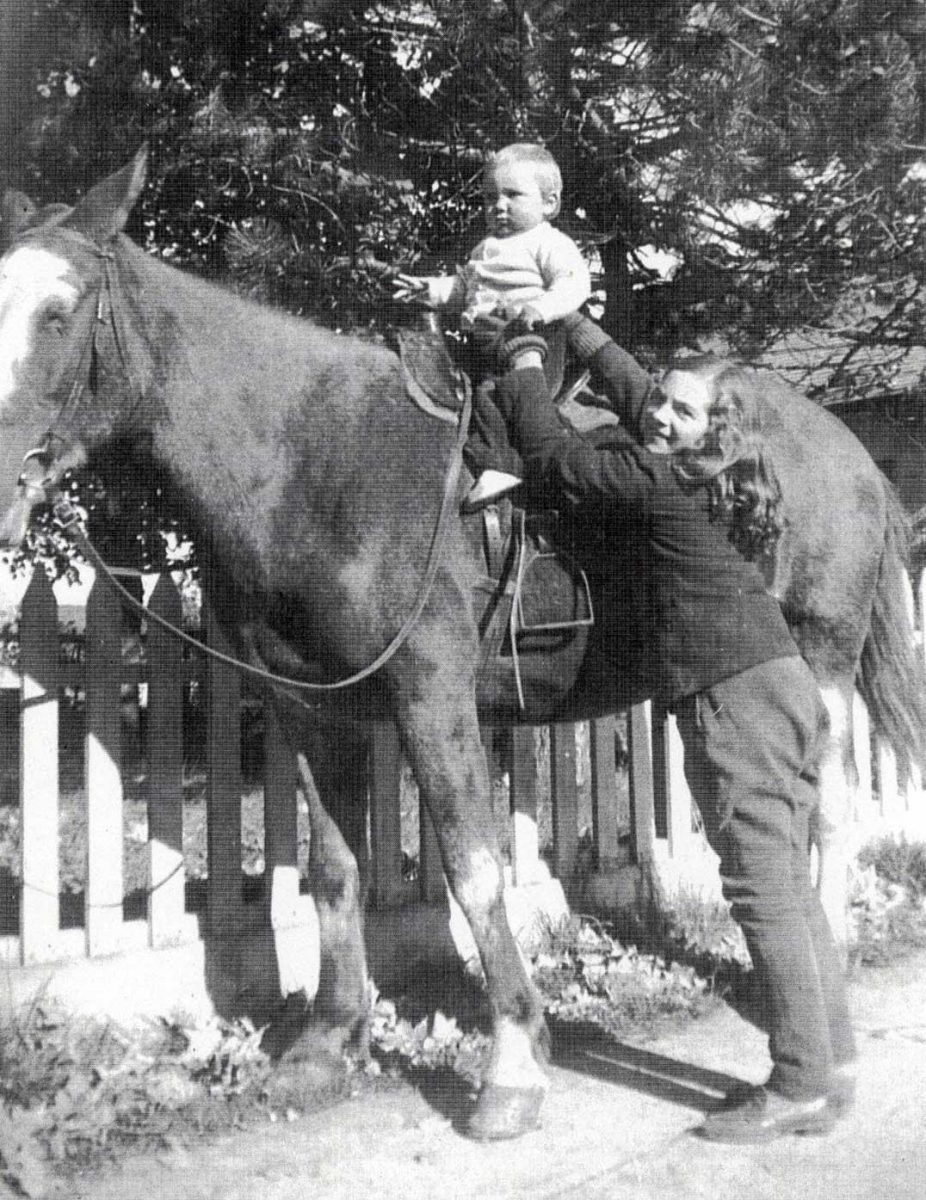

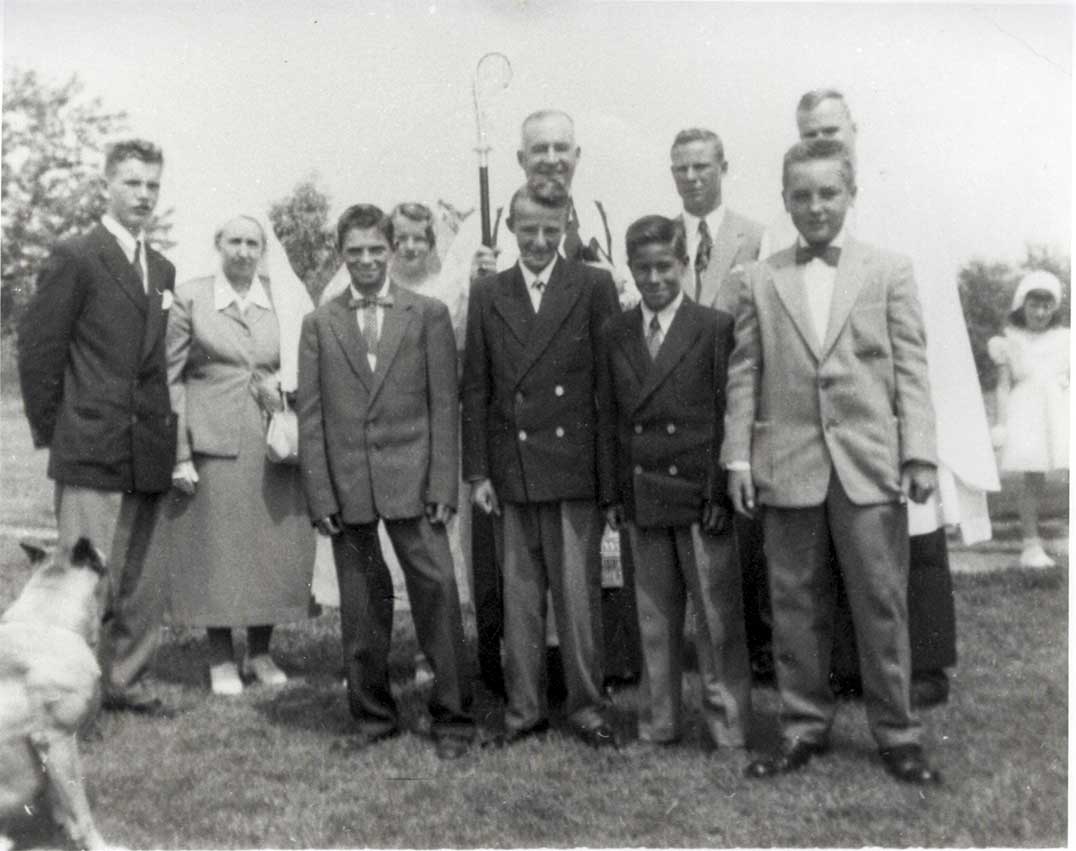

Katherine met Art Mastin in Manitowaning after she noticed a young good-looking man staying at the Queen’s Hotel for the opening of the then-new Irving store. He had tossed a coin to establish his staying or leaving. He stayed. Katherine purposely ran her car into a ditch to inspire both his gallantry and his attention. The ploy worked well and ultimately led to their elopement, sealed in a Sheguiandah church, with two old maids as witnesses. Daughters Helen Margot and Catherine Anne were born first and were joined by brother Rennie on September 4, 1943.

During the depression, local folk came to the store, crying, and Arthur would give them credit. Art did a multitude of extra jobs for his family, including a mail-run over the ice. A ‘chimney-sweep’ named Mr. Leveque, who had lost his fortune in the fur business, became a friend. Mr. Leveque recommended that Art purchase the creamery in Manitowaning in time for the economic recovery. “Eventually dad gave in and tried to raise the money for a down-payment. Finally, in 1940, he consulted a bootlegger in Little Current and got his deposit in brown paper bags and bought the creamery.” He was by then also operating his late father-in-law’s business that included both groceries and clothing. It is the stone-facaded storefront with stained glass front windows that now is the working home of the Debajehmujig Theatre Group and is now called Debajehmujig Creation Centre.

“Dad felt it was important to include ‘critical integration’ of supplies and services to optimize profitability. He was ahead of his time, but it was too hard to keep up. He bought a transport company that delivered to Sudbury in 1950. He also started a verbal partnership with Dave Sim to start a pig farm and use the extra buttermilk to feed the pigs, which got huge. For recreation, he liked harness racing, popular on the Island and in many places throughout Ontario and Michigan.”

“Mother had a cousin, a ballerina, Aunt Helen who lived in Chicago. Aunt Helen did something special for us. My first memory at age five was pulling up to the Gore Bay airport with my mother. There was a DC-3 sitting there. I was frightened, apparently amusing the pilot with my colourful language. We flew to New York and stayed first in Helen’s dark apartment. Then back on the plane to Florida. Once there, we were ensconced in the Flamingo Hotel where a big yacht was sitting at the nearby dock. It had a captain, two sailors and a butler. For the next month, we toured the Florida Keys and were treated like royalty on this lavish boat. They even let me drive it. In time, we came back to the reality of everyday life in Manitowaning.”

“When I was 11, my mother who loved travelling, decided to go on a European Tour with me and Viola, wife of Manitowaning Doctor Moody. We got on a big ship. A young professor taught me about Europe with just a map. We toured Europe by bus. Germany was humming, nine years after the war ended. Jackhammers were rebuilding bombed cities. Italy, by contrast was quiet; nothing that interested an active 11-year-old boy.”

“At 13, I was working in the creamery, spending my summers in the delivery truck meeting some of the farmers. It was just natural that I would work and help.” The creamery was a successful venture in eastern Manitoulin. Wagg’s supplied the West End. Pigs and butter got to the lucrative Toronto Market by transport, which returned with needed supplies.

“After public school, I went to high school in Manitowaning. High school held 31 kids from Grades 9 to 12. After Grade 10, my parents wanted me in a private school, but I stayed with my cohort, partly to stay with friends and partly because I was playing a lot of hockey at the time, half my time in Wiky and half in Manitowaning. Don Fisher was my coach in Wiky and my dad, the manager for two years. Stuart Shawanda was the top player.”

“At 16, I stayed with my uncle and his wife in Thorold to play hockey for the Thorold Juveniles. When a scout visited here, for the price of a soda, I signed a C-form; an emotive experience and a distinct honour. I didn’t tell my parents. Then at 17, dad was impressed that I was invited to the Jr. Canadien’s Hockey Camp with Scotty Bowman, the most winningest, popular coach at the time. I had heard on the radio that he had come to Thorold just to see me and I felt I had betrayed him because of my C-form. Signing that form meant I was classified as a professional player and could not play for any university teams in the USA or Canada.”

“I did go to the Jr. Habs hockey camp and was met in Ottawa by Scotty who showed me his bankroll and said, ‘help yourself.’ I was shy, so took just two twenties for expenses. My first cousin had convinced me that should I pursue this line of work, I would wind up making $20,000, get injured, and have no teeth by the time I was 30.” So, after that week Rennie returned to Thorold. He also had compelling offers from Dartmouth and Cornell Universities, but to no avail. “The coach at Cornell tried unsuccessfully, over two seasons, to get me released from the C-form.”

Finishing high school became the next goal. At 18, the Chicago Blackhawks head coach, of the same farm team that had seen players like Bobby Hull, tried to recruit Rennie for their farm team and get him into McMaster University. St. Lawrence University in New York (near Cornwall), which rented their own planes, approached him as well. “Little did I know how that C-form would affect my life.”

Rennie took economics and philosophy at Western for three years and played Jr. Hockey. “During one game, I had played well, but in the dying minutes of the third period there was a tragic turn. I accidentally hit the eye of an opposing team member with my stick. He lost his eyesight for life and I was devastated. I left hockey for a year.” After Western, Rennie was off to Toronto for law school. The day he wrote his final exam, he ran into some former team members who had joined the WHA (World Hockey Association) and were earning in excess of $100,000 a year. This compared to $12,500 Rennie would make in his first year and practicing law.

“I started with the new Sudbury law firm, Desmarais, Keenan and dealt with all major aspects of the law. I was introduced to a young secretary, Edith Lynne Kiley, 19, originally from Creighton Mine, the second of eight children. It was her first job too. It seemed that fate was on our side.” Lynne was assigned to the new articling student and the rest was history. Rennie headed back to Toronto to article for McCarthy and McCarthy, the largest law firm in the country. “I finished my bar exams and married Lynne in 1972.” They had three children, Rennie, Ryan and Jonathan.

In the early 1970s, Rennie met some people who had building experience in Sudbury. The city was going through a construction boom and there were lots of liens to deal with for the lawyers. Meanwhile, Lynne enrolled at Laurentian University to get a degree in history with a focus on Russian Studies.

In June 1976, the family moved to Montreal where Rennie would work for an accounting firm. One year later, he moved to the Verchere Gauthier Law Firm which acted for the Swiss Bank Corporation. Rennie became aware of international issues. He was specifically interested in tax law, including domestic and international trusts. This company regularly dealt with organizations in Iran and the Arab Countries.

In 1978, Rennie found himself entrenched in the first-class section of a 747, drinking champagne, heading for Iran to deal with a $225 million housing contract involving the southern oil fields of Iran. “I got to know the people and a new culture. The president of the company in Iran had a relationship with the Shah of Iran’s niece, Simine, who was head of protocol for the court, so I got to know her well.” She helped Rennie understand the nature and complexities of the political system. “We continued to be friends until she died a few years ago in Los Angeles.” At one point Rennie was so well-versed in Iranian activities, he wanted Lynne and their son to move there.

The firm opened an office in Toronto on the 64th floor of the First Canadian Place in 1978. Rennie was the representative for the Montreal company and others joined. That same year, Rennie took his mother on a trip to Kuwait and Egypt. “I soon realized that she had two mickeys of vodka in her suitcase. We arrived at a vast space in the airport, marble counters and uniformed men with lots of time to check us through. I told her that they would fire me and send me home, or lock me up perhaps, if she didn’t get rid of the vodka” because of the strict prohibition against alcohol consumption in these Muslim nations.

“She ran to the washroom and tried to do that, but a cleaning lady was there watching her, so she put one mickey under each arm and came back out, walking slowly and rather stiffly. I was sweating but I watched her charm the airport staff, while maintaining a very prim and proper countenance. As she approached the guards, they smiled at her and passed her through without a search. She had an adventurous soul.”

Some years later, the revolution in 1979 indicated that the reign of the Shah of Iran was ending. The USA was no longer supporting him, and he had developed prostate cancer. Shooting in the street had begun. His supporters seized all his assets, weapons and $23 billion. Rennie coordinated an effort to send the Shah to Canada with Pierre Trudeau’s agreement. “Henry Kissinger, US Secretary of State and National Security Advisor also became involved and instead, a cancer operation was scheduled for the Shah in Panama. The Shah was concerned that he might die on the table, since he was no longer supported by the USA, so left Panama and went to the Bahamas instead. Egypt took him in, and the Shah died there later, of cancer.”

Meanwhile the revolution was on. Rennie recalls being in a bar with another Canadian in downtown Tehran when a commotion outside forced them to leave for the airport rather suddenly. Manoucher Etminan, a friend, had taken off the unpopular royal plates on a fast Italian car, but they didn’t get far. “The car was blocked at an intersection by men with machine guns, which soon spit out a hail of bullets. My companion from Welland, Ontario was wondering what the pinging noises were. I yelled at him to get down, those were real bullets. Somehow, we managed to get out of that difficult situation with help from our manager and the Shah’s sister, who knew where we were staying. Eventually we got to Toronto again and we helped Manoucher and his daughter to emigrate to Canada. He ultimately built his own successful bakery, Manoucher’s Bread. His Persian-inspired breads are still sold across Canada, and on airlines like British Airways.”

A year later, Rennie was getting strange calls in Toronto. “It seems Ryan O’Neil, the actor who was nearby, somehow heard about this mystery and came up to see me. Ryan was dating Simine’s daughter. He told me the husband of the Shah’s sister had been calling and he wanted me to go to Los Angeles immediately. In LA, I found the Shah’s elderly mother propped up on pillows within a steeply perched castle with a moat. She was safe there from the anger of Iranian students in Los Angeles. She wanted me to help her with some funds.”

“Simine, along with the Shah’s mother and many other Iranians now made their homes in Los Angeles. Simine had earned money for her work in negotiating the housing contract and she left Iran on the last plane out of Tehran, with her money. I had often been in the Middle East when things had been going wrong and I tried to help as much as I could.”

A steady flow of Middle Eastern contracts came to Rennie. After a few years, the new Iranian regime asked Rennie to set up the largest onshore drilling contract in world history at the time. He arranged a successful contract with a Calgary company. In all, this Sudbury lawyer made about 150 visits to the Middle East and 200 trips to Europe.

Back home, Lynne felt privileged to become acquainted with the Anishinabe world on the Island. On Manitoulin, she met and interacted with local Indigenous people that shopped at Mastin’s, the family store that Rennie and his family also managed in addition to his international legal affairs. Their outlook on life and their values became a revelation that added meaning to her own life. When Rennie and Lynne’s sons were old enough, they were encouraged to play for Wiky teams too. After having been exposed only to ‘cowboys and Indians’ on television, their eyes were opened by the reality of Native life; these were great people.” As an adult, Rennie often drove into Wiky on a Sunday to visit friends and elders. “I enjoyed chatting with and learning from them.”

Lynne was busy, helping where she was needed, but always being a mother and wife first. She became a Director for the Ontario College of Teachers, helped her husband run his legal practice and other tasks as needed. In 1975 Lynne accompanied her husband, visiting several Soviet republics. Seeing life in these places helped her realize she had a good life on Manitoulin: the warm ambience, the Anishnabe culture and the comfortable routine of the family business. The Lake Manitou cottage also became a focal point. Sadly, Lynne died in 2010 of colon cancer.

Her obituary said: “Whether it was being the primary caregiver to her mother-in-law, managing the family businesses, serving on the Board of Directors of the Ontario College of Teachers, or running her husband’s legal practice, Lynne somehow always managed to do all that was asked of her, and to do it in accordance with the exceptionally high standards that she set for herself. She had also, frequently, helped ladies negotiate the legal and health systems in her own community.”

Oldest son Jonathan is an artist. Rennie Jr. is a lawyer and president of the Canadian Media Producers Association. Ryan is in security.

Rennie has no regrets apart from having signed the C-form as a youth. “When I look back on my life, I am still a true Islander at heart. My life so far has been a wonderful adventure; a rewarding job where I met so many interesting people from different countries and regimes. At the same time, I was sharing my life with an amazing lady and three great children. Through it all, we always had our retreat, the family cottage on Lake Manitou, our refuge in the storm. Manitoulin established my roots, and I will always cherish that.”