by Petra Wall

Cliff and Nelda Orford

“I am the last of the Orford boys of my generation walking on Manitoulin,” Cliff shares, “most of my siblings and close extended family have passed on.” Cliff and Nelda welcomed the writer to their fine home on Union Road. It was a bright sunny day and the living room featured numerous plants, one with bright red leaves, glowing in the sunlight. “I built this house for our family 35 years ago,” Cliff offers by way of introduction.

This Manitouliner has spent decades, cutting timber, building homes and learning skills that a man of the land needs to prosper. Nelda has always been by his side, starting her working life as a young teacher at country schools in Mills and Honora, later as a weather station employee, driving the school bus with her husband, and of course, raising their family of four.

Cliff’s maternal grandparents George and Sarah Badgerow farmed near Gore Bay, where the hydro transfer station is today. They struggled with scant topsoil and lots of rocks, familiar to farmers on the Island. Their daughter Viola Eliza Rebecca married Ed Orford and became Cliff’s parents. “I was born on September 22, 1927 in Saskatchewan, where my parents had moved to in 1921. A lot of dust and grasshoppers hampered their dreams of becoming productive wheat farmers. The family moved back to the Island in 1928 bringing four children with them. Eventually, there would be seven children: Lloyd, Delbert, Austin, Cliff, Les, Edna and Reona.

In the years before the snow plow cleaned the roads, mail was carried by horse and sleigh from Gore Bay to Massey, across the ice. “One day we found out that my grandmother was very sick. Dad stayed home to look after the farm and mother took four of us on the mail sleigh across the ice to Gordon Township on March 28, 1928. Sandy McDermid drove that Purvis team. I was only six-months-old. I was told that the ice remained strong and we made it safely both ways.”

Ed and Viola’s 100-acre farm, with the old log house and big barn, was located near the Mills cemetery on Union Road. Brother Delbert later inherited the farm because eldest son Lloyd had been killed in the war, one month after D-Day. He and his troops had been cornered in a small village in France. Air support was called in but, sadly, the report indicated that the Allied air force mistook them for the enemy and 88 of them were killed by friendly fire. It was a sad day in July of 1944. Delbert had also been in Germany three days after the war ended. He had come close to downing a plane prior to the end of the war by shooting off the cable between two enemy planes. “We found out later that Mills had sent the greatest number of soldiers to the war effort and yet it seems Lloyd was the only death in this township.”

Cliff started school at age six in Mills Township, along with 37 other kids scattered among nine grades. “It was a daily four-mile hike to and from school, with my tin lunch can swinging by my side. I can honestly say that during all my time there, I was only driven in a vehicle four times. There were three of us in Grade 1 and we gained one more student a year later. “I remember one poor fellow who was teased a lot because he couldn’t spell at all. If the teacher asked him to write words down, they would all be wrong.” One wonders if he might have had dyslexia before instructional staff became aware of this disability, about 40 years later.

Cliff recalls the squirrel that had been annoying the kids playing baseball at recess. It would constantly get in their way. Perhaps it was instinctive when the unfortunate squirrel picked a bad time to come out of the wood pile. Cliff was up at bat and he swung at the rodent instead. “All the kids had been challenging each other to get the squirrel, but I got him. My victory was short-lived, though, because I also got the strap.” After Grade 9, in 1943, school was over for 16-year-old Cliff.

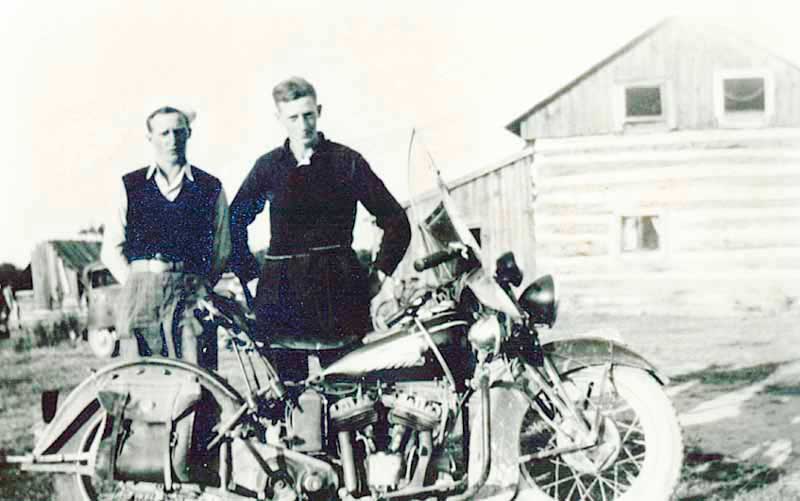

“I associate those war years with ration books. You were restricted to limits in the amount of sugar, butter and other items so the soldiers would have enough to eat.” Nevertheless, there was always lots of stuff to spend the money on such as his first motorcycle when he was 18, in 1945. “I loved the freedom of riding that bike.” It was five years later before he began to think about more formal acquisitions. “I was 23 before I got my first suit.”

“That first winter, after finishing school, I cut pulpwood six days a week with Jim Baker at Hawken’s Mill (at Swift Current, between Birch Island and Little Current) for $45 a month. The wood would be piled near the shore where a freighter would come to pick it up. In the summer, Cliff drove a steam-driven carriage to pile cut wood that had been collected in booms and pulled by tugs from local bays and islands, like Wardrobe Island.

“We had a jack-ladder set up to take the wood from the water right up to the second floor of the sawmill. The saw itself took up most of the first floor. The jack-ladder was a continuous moving ‘chain and trough’ apparatus that pulled the wood right up to the saw where it would be cut into boards. The boards came back out on the jack-ladder to be piled in the yard. Subsequently the wood was planed and then shipped out by rail. Cliff worked here for about 12 summers.

Nelda was born on March 17, 1933 to William (Bill) and Ethel Victoria Shaule (nee Clark). Her dad was renting a farm in Cloudsley, seven miles northeast of Bruce Mines. The family ran the local post office. Bill and Ethel soon bought their own farm in the same area. “We did mixed farming, growing small crops and raising chickens,” Nelda muses. “I remember being surprised that it took the hen three weeks of sitting on the eggs to hatch the small chicks.”

“I had three brothers and two sisters. Dale, who worked in the steel mills in Sault Ste. Marie; Darrell, who became a United Church minister in Lucan, just outside of London; Dwight, who died as a baby of nine months of pneumonia; Gail, who passed away at 16 from heart problems; and Myrna, who was also just a child when she died of kidney problems.” Nelda was the eldest.

“My grandfather, John Shaule, had a mysterious end. He got up one day in Cloudslee and hitched his horses to his sleigh and left over the ice for St. Joseph’s Island. He was to pick up a load of hay there. We never saw him or his team of horses again. No sign that he had fallen into the lake ever emerged. Years later, our son Gordon ran into someone who remembered the story of my grandfather but he had no new information. After that my grandmother Elizabeth (nee Adams) lived alone but ran their farm with the help of her four adult sons and two daughters.

A shed with two doors was built and attached to the house for storage. A big yellow dog was purchased to protect grandmother. One day, the dog tangled up with a porcupine and predictably suffered a mouthful of quills. “That day my uncle Sandy went to visit grandmother and found her in despair. ‘Please help me get these quills out of Chum’,” she pleaded. “’Sure, there’s nothing to it. You hold the dog and I will pull them out’.” It seems that holding the dog was the hard part.

They decided to call him into the shed and then close the door on his neck to trap him in place. This did not work the first two times because the dog must have realized that this was not working well for him. Finally, they did slam the door on his neck and the quills were pulled out, but at an additional cost. Poor Chum was moving less and less. “It seems that we held him so tight that he collapsed from lack of oxygen when we finally released him. We were aghast! At first, Chum just lay there and we feared he had expired. However, he eventually recovered and lived a good long life.”

“I never learned how to milk a cow but I did do a lot of work on the farm, as we all did. I was often asked to stay in the house with my younger siblings while mum and dad milked the cows and fed the calves.” Nelda liked school, especially spelling. She stayed to finish Grade 12 and then went right into teaching. “Circumstances made me a teacher,” she attests. “They needed teachers when I finished school and they didn’t ask for a certificate, so I became a teacher.”

“My teaching style was a bit different from another teacher who wanted to have absolute power over the kids. I felt there should be some give and take on both sides,” she shares. “I tried to teach them by getting their attention in a positive way, so they would want to learn. Discipline can be applied in different ways too; it doesn’t always have to be the strap. Families often doled out the physical discipline so I could use alternate forms. I found I didn’t have many problems with the kids even though some of them were close to me in age.”

Cliff and Nelda met in 1951 when Nelda was teaching at Mills school. Cliff was one of the gang that included Nelda from time to time. Nelda also taught Cliff’s sister, Reona, in Grade 6 so she ran into Cliff regularly and in due course they found they enjoyed each other’s company. “We attended lots of functions but didn’t go to dances because Cliff didn’t like to dance, but we did spend a lot of our time together.”

Cliff was into his six-year stint at KVP (Kalamazoo Vegetable Paper) in Espanola, the business now owned by Domtar. “One day Cliff came from ‘KVP land’ for a visit and saw me knitting a pair of socks. He was intrigued, ‘why don’t you make me a pair of work socks?’ so I did.” This little personal request seemed very fitting for a young man who wanted a more permanent relationship.

Nelda started to teach at Honora, moving into the main house at Silver Birches Resort. “I had left Mills because they got a teacher with a certificate,” she explained, “I didn’t have one of those.” Nelda taught 13 kids, 12 boys and one girl. “One of the students, Doug Hore, would become a well-known musician on Manitoulin and has been a barber in Little Current, in the same location, for 55 years. Nelda continued to see Cliff and they soon set a date.

They were married on August 22, 1952 by Reverend Kaill in Gore Bay. The small wedding was followed by a honeymoon in Niagara Falls to where they travelled in Cliff’s beloved 1950 Pontiac.

In 1960, Cliff was working for Gerald Runnalls. “We worked all over the island, including Carter Bay, Michael’s Bay and Providence Bay where there was another sawmill. The booms brought the logs in and they were trucked to the saw mill.

The couple had four children, Laurie, Cheryl, Gordon and Donna. “Laurie loved horses so we bought her a steed from Sandfield for $20 down. This deposit would hold the horse for three days until we made sure that Laurie was happy with the purchase,” Cliff adds. “Sunny the horse, would shake your hand but you had to warn people first so they wouldn’t be knocked down by his enthusiastic greeting.”

Laurie rode him everywhere without a saddle, taking great care when they approached the edge of the lake. Sunny would slowly slide down and bury himself in the water, taking her with him. She had to jump off quickly, or give him a pop bottle. Sunny could take the top off the bottle with his teeth and then he would hold the can up and drain it. “If you were unfortunate enough not to have the foresight to bring the pop, you had to really holler at him to get him back out of the water.” The family also had a dog that slept on the bed with Gord and a cat named Sam.”

“We travelled a bit too, taking three of the kids out west to Alaska and Dawson City where we looked for gold in ‘claim 35.’ We saw Vancouver. On another trip, we went back to Saskatchewan to show the kids where I was born,” Cliff adds. “When I was younger, Austin and I and two friends had returned to that province, near the Blackfoot Reserve, at harvest time. The work was hard and long, but we had fun too. We saw billygoats and elk for the first time.”

After the pulpwood years, Cliff started working with Charlie Middaugh, building cottages, houses and a lot of chimneys for about eight dollars a day. “Blocks and bricks went into the chimneys,” he adds. “We also tore down some buildings in Gore Bay and got paid $100 a day for that work. We built this house in 1979 with the help of our kids.” Cliff felt strongly about fair play in the construction industry on Manitoulin. He stood up for a few carpenters who worked more slowly but did good work. He didn’t think it was fair to let them go, just because they took a little more time.

“Both Nelda and I also drove a 60-passenger school bus for 20 years until we sold the bus in 1989. The first bus cost us $6,800 and the second one was a pricier $32,500. I got a certificate for all those years of service. After that, I did carpentry work up until last year when walking became more of a challenge for me. Meanwhile, Nelda had spent many years at the weather station in Gore Bay.”

Cliff’s brothers Austin and Les both died of cancer, Austin at middle age and Les when he was older. Edna lives in Kelowna, BC and Reona in Mississauga Beach near Owen Sound. “We have 10 grandchildren and 12 great-grandchildren. Gord’s son Mathew, an air-traffic controller, will be going to Toronto for extra training in radar operations. His daughter April teaches in Gore Bay and daughter Ashley lives in Sudbury.”

“Donna’s son Curtis is a dispatcher at Manitoulin Transport. He looks after the ‘ice wagons’ that go north over frozen lakes in far Northern Canada every winter. Her other son Kenton worked for INCO, fixing mine breaks. Laurie’s son Ryan has a drilling outfit for oil wells and he does welding too. His daughter Leslie does catering and other son Colin owns 16 tractor trailers and works in the fracking business all over the Arctic and in the south. Cheryl has two boys; Kyle, a welder in Hamilton and Kristofer, a carpenter in Toronto.

“The most important event in my life was finding Nelda, getting married and having our four children,” Cliff holds. “They all turned out well with no bad habits. Our youngest is 57 now but we see them all, including the grandchildren and great-grandchildren, from time to time.”

“If we could go back in time, I don’t believe there is much we would change. We did what we had to do to survive. You ask what I fear most. There is not much that I am afraid of,” he adds, “except snakes.” We do have a skunk who must be respected. He has made his home in our eight-foot square shed. As long as he behaves himself he can stay. If he fires his weapon, he will go. I will get out my 12-gauge shotgun.”

“I am happiest when I am welcoming a new person to our family; a new person that has all 10 fingers and toes and is healthy,” Nelda muses. “All 36 of our extended family members are happy and healthy. This August we will have been married for 65 years.”

“Manitoulin has been good to us,” Cliff attests. “This is a friendly place to live when you compare it to big cities. They are more dangerous with all that traffic. People on the Island are great. We had but two dollars to our name when we married and if it hadn’t been for Bill Middaugh getting a store credit for us, we would have been very hungry. Charlie Middaugh, my boss, also managed to fire me three times when he was annoyed,” Cliff offers, smiling, “but I just kept on working and he was happy with that. He had a good heart.”

“If you are sick here, people really come through and help you out too. That was very true in the early years but it is true today also. There is a lady that lives near here and she gets help from her neighbours, including us. It is so much nicer to know that support is here if you need it. That’s what makes this place special. We are very happy here on Manitoulin.”