Railroad Memories

Next month, August, in the Old Mill Heritage Center, curator Rick Nelson will be featuring a presentation about our early railroad years. We are introducing the railroad theme with a bit of history, featuring the memories of a few Island residents and their connections with those early Canadian and Manitoulin railway years.

When Greg and Rick Niven, both living on Manitoulin Island, headed west in their ‘sleeper’ cabin, on the scenic Canadian National (CN) Railway, they were bringing their father Paul’s ashes to the final resting place in Victoria. Paul had been a land developer and his wife a stenographer in the Victoria, Vancouver Island court system and later she worked for Litton Systems, the ‘high-tech’ company that built the ‘Canada Arm’ for the space program. Greg and Rick’s siblings, Nancy of Parry Sound, and Jennifer, of St. Thomas were happy with this final tribute. This trip would be the fulfillment of a last wish by their dad to return to the place that he grew up and loved. After a few of his ashes would be scattered in the Pacific Ocean, he would be laid to rest beside his wife in a Victoria graveyard.

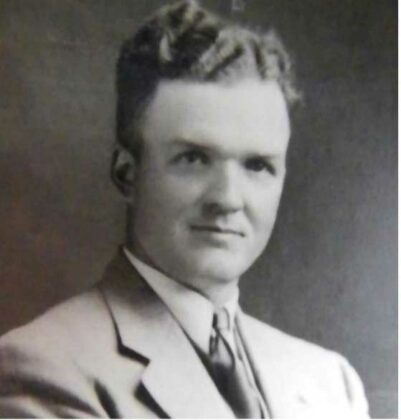

Their family had enjoyed a deep connection with the ‘CN’ Railway, starting with maternal Grandfather Donald ‘Jiggs’ Marquis, born at the turn of the century in Rainy River. Greg and Rick told the train staff, “Our grandfather played a vital role for this railway.” Staff members gazed attentively and answered ‘really?’ They left and came back a few minutes later. “There is a retired gentleman on this train, someone who remembers your grandfather, ‘Jiggs’ Marquis! Greg and Rick were brought to the ex-Canadian National Railway worker, and they happily shared a few nostalgic memories and had a photo taken with him. The old gentleman also remembered that Jiggs had earned a 50-year pin. It was serendipitous that they had run into this gentleman on this epic journey for their dad.

“When ‘Jiggs’ first looked to the railroad for a job, he lied about his age, 16. He claimed to be 18,” grandson Rick Niven shares. “He stayed for 57 years, starting out as a call-boy, sleeping in the railway terminal. He progressed to yard worker, then to brakeman, fireman and finally, conductor. His first ‘train’ job was on the freight trains that delivered goods to all parts of Ontario and Manitoba. He had more seniority when he began with the passenger trains, moving people and luggage to both the east and west coasts. When he finally retired, still a conductor, with his 50-year pin, he was one of the most senior members of his peer group.”

“We believe that he met his wife Marietta Chouette at Hornepayne station on the railroad line. This was where her family lived. Jiggs and Marietta had four children, Suzanne, my mother, Claudette, Kathryn and son, Jodi. Daughter Kathryn shared that dad had saved her life twice, “once when I jumped out of a car as a child and was set to run into an oncoming car. The second time, I was falling asleep at the wheel, when suddenly, I heard the shrill of a train whistle!”

Jiggs’ family would frequently be on his train. “They would visit the caboose where the office, bunks and other equipment was kept. Two ‘lookout’ windows in the caboose allowed oversight of the train and its surroundings. The children would also be brought up to the engine cab, to see the engineer and the firemen who would shovel coal into the firebox that produced the steam. Today diesel engines don’t require a fireman or a brakeman. “Since family members rode the train for free, this allowed our mother to visit her family in Hornepayne. Grandfather never got his driver’s license, so the train must have been a valuable transportation source for him also. He did buy a car once as an investment, but it just sat in the parking lot for six years in the 1970s. It was never driven.

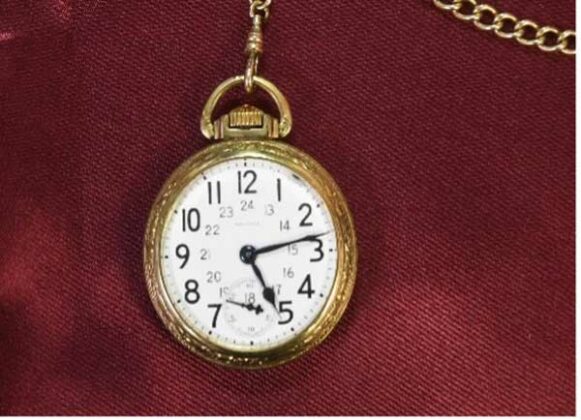

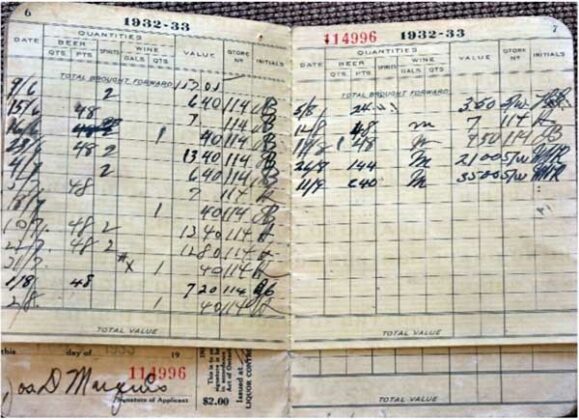

“Jiggs didn’t believe in banks and kept his hard-earned cash close by. It is likely that he didn’t have a bank account until he was pensioned, and the government needed a destination for his payments. A photo of his pensioner’s slip is shared. He was employee #377 which was stamped onto his 1941 slip. His pension gave him about four dollars and forty-three cents a month.” Among his valuables, Rick also found some personal letters from his family and an ‘Individual Liquor Permit’ issued after prohibition from 1927 to 1962, the “local option” time of controlled alcohol sales. Jiggs, like all others, had to record any purchase of liquor on this personal card which was valid for one year.”

“Grandfather recalled two serious accidents during his railroad years. One was experienced by a friend of his. There were frequent washouts or snow slides that could prevent the train from moving for several days. This derailment produced a serious wreckage that saw one casualty. His friend may have been saved by being in the proper place for a conductor on a moving train, and that is at the back of that train. Another time, the train was derailed while carrying cattle. Many cows died in the fire and the remainder had to be shot, as there was no food for them. They had to wait a week for help. Often when trains were wrecked in the middle of nowhere, the wrecks would be buried, rather than repaired.”

There were other family ‘railroad’ connections. “Joseph’s brother, Nels Marquis had three offspring, Patty, Philip, and Tony. Patty Patterson later became the train master for CN, working at Union Station in Toronto. We often visited her in Capreol where her family lived. She taught me how to swim there,” Rick adds. “Patty’s brother Philip also worked for the Canadian National Railway. Brother Tony became a senior manager for Canadian Pacific, ‘CP’. There is an island connection also. Patty’s son, Mike Patterson became a policeman on Manitoulin. He was stationed in Gore Bay.”

More railway connections

The following excerpt is from the book ‘Dr. John Francis ‘Jack’ Bailey, A Medical Pioneer of Manitoulin, author Petra Wall: “One eventful trip was in a baggage car to Sudbury. The train was headed for Buffalo but would stop in Sudbury. A 12-year-old boy had slid down the bank of a hill in a sled, onto the main road and was hit by a car. He sustained a collapsed lung and needed more intensive care. The daily train had just left Little Current, and the one passenger car was full.”

“The train conductor got the emergency call, and he stopped the train in a nearby curve just on the other side of the bridge. Dr. Bailey drove up to the spot and loaded up his passenger, a very sick little boy, and his mother into the freight car. The trio endured a three-and-a-half-hour ride to Sudbury. Dr. Bailey refers to the ride as the ‘Agony’ because of the endless, rocky, ride in a freight car not meant for humans. Dr. Bailey got pictures from the family of the healed little boy for years to come.”

Now and Then memories

Keith Hopkin shared in his Now and Then story, “I am still fascinated with early modes of transportation, especially those that serviced Manitoulin, the place of my birth. Steamships and later trains brought goods and people to the Island before the automobile became popular.” In the early 1970s the love for trains was reignited at his brother-in-law’s place in Don Mills where he saw a Canadian Pacific steam locomotive pulling vintage ‘Tuscan-red’ passenger cars across a huge steel trestle. Ontario Rail ran these old steam engines for a group of interested members. “I was entranced with the might of these old iron horses, and I had to join the group. Making models of them seemed like the best way to celebrate this historic transportation system.”

“In early years, the trains stopped at Little Current and picked up coal to be delivered to locations in Northern Ontario. The freight-hauling steamships would pick up the iron ore pellets that the trains had brought from the mines in Sudbury. The trains would bring passengers and freight from Toronto to the ports of Owen Sound and Collingwood. From there, steamships would transport their passengers and freight to ports on Manitoulin Island, Killarney, Blind River, Sault Ste. Marie, Thunder Bay, and other ports.”

“In my basement, I built an ‘HO’ scale model railway located somewhere in Northern Ontario during the 1950s,” Keith continues. “‘HO’ is the term commonly used for 1/87th scale trains. They are about 1/2 the size of the first toy trains that were called ‘O’ scale that were produced in the early 1900s. HO trains are the most popular size in the world today. I recreated two small towns, lakes, rock formations, trees, a river, a Canadian Pacific rail yard, a beaver dam, and a small harbour in miniature. Visitors are enchanted and amazed by the realistic trains that stop for passengers and freight at the Frank and Conley’s Corner stations.”

“My father used to ship cattle to southern Ontario and to the USA by train from the stock yards at Little Current. My friend, the late Richard Chrysler, an exceptional modeller, built ten Canadian Pacific stock cars for me. In the real world these could be used for cattle, sheep, and pigs.”

Keith Hopkin has been enthused about trains and steamships for much of his life. Keith helped Little Current find a ‘Jigger’ just like those used by the railroads for decades. “They were used by track gangs to inspect the rails and roadbed for their section of track and to make any necessary repairs. Jiggers also ran behind trains in hot weather conditions to put out any grass fires caused from red hot coals from the stacks of the steam locomotives.”

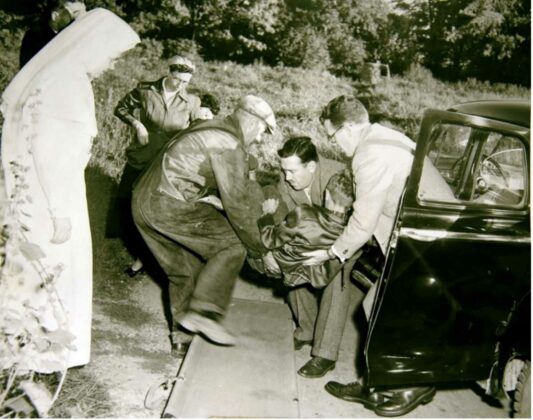

Keith made arrangements with Bill Caesar who took delivery of the historic vehicle when it arrived from southern Ontario on a bright sunny July 7, 2013. Mayor Al MacNevin, Bill Caesar, Rick McCutcheon and the father son team of Rod and Scot Wilson, who delivered the CPR jigger, provided muscle power to get the Jigger off the flatbed truck and onto pre-set rails beside the information centre. Afterwards, a jubilant team, including Keith stood for photos to commemorate the event. The 100th anniversary of the Swing Bridge that links Manitoulin to the rest of the world was scheduled for the following week.

In the article, ‘Vacation near Manitoulin Island’ by Keith Hopkin, we are told that on Saturday July 31, 1943, a special nine-car train left New York on a secret mission for President Roosevelt to have a one-week holiday in Birch Island. He occupied the ‘Ferdinand Magellan’ his private car and fortress. He was surrounded by staff, secret servicemen, his personal physician, and railroad officials. Chief William McGregor of Birch Island was the proud host for Franklin Delano Roosevelt when he arrived at the community for a week of fishing.

Fighter planes brought mail and documents twice daily, two speedboats with guns and bomb bays stood ready. All roads and trails were patrolled for a radius of five miles around the camp. While the president was fishing, he was escorted by three boats bearing eight Secret Servicemen and three Royal Canadian Mounted Police. A 300 -foot naval vessel with 85 men guarded the only marine approach to the resort.

From one Now and Then column, we learn that the train stopped along the way and a young Archie Corbiere remembers this day quite clearly. He was picking blueberries with his parents at the Fox Lake turn-off, near Espanola. A bright shiny, black, and bronze steam engine came into sight.

The young lad was dressed up and he sensed the excitement among the people gathered. The train stopped and Archie was lifted onto the back of the train. He was nine-years-old when he met President Franklin Roosevelt that day. He doesn’t remember much about the conversation. He just recalls a kindly grey-haired man who spoke to him for a few minutes. Community members also recall the presidential train, surrounded by security personnel, stationed in Birch Island. They also recall a fleet of boats heading out to fish in McGregor Bay. This may have been one of the last major vacations this American president had since he had to navigate through two more years of World War two. He died just after the end of the war in Europe in 1945.

Lorne Ebel shares in his story, “Later dad worked for the Timkin family of Timkin Rollerbearing Company, of Canton Ohio, managing their private residence and their yachts, near Whitefish Falls. When then-President F.D. Roosevelt came for his famous fishing trip, he stayed with the Timkin family, prior to his Quebec conference regarding the ending of the war. Local fisherman Donald McKenzie was the guide for the president.”

Lorne was also one of three captains of the Jacqueline from 1942 until the service was discontinued when the train bridge at Little Current was planked and opened to car traffic. “The ferry transported cars and people. Three fully licensed captains were required because the ferry ran seven days a week. She ran every 30 minutes between 6:30 AM and 11:30 PM, docking at midnight. This worked out to at least 24 trips a day or 168 crossings in a 48-hour week. The captains had two days off each week.” The bridge in Little Current had been built for the railway at first, allowing the mail train to arrive and depart once a day. The rest of the time the bridge was left open.

Other Now and Then recollections of the trains:

Vi Vincent was born April 19, 1904. “My first trip to Sudbury was by train when I was 12 years old, about three years after the Algoma Eastern Railway was built”. “There was no car traffic until the road to Espanola was built about 1930. Before that year, a horse and cart had to use a ferry to get across the North Channel.” The swing bridge opened for cars in 1945.”

Gert Aelick Cooper shares that her paternal grandfather Thomas James Batman was born in Liverpool in 1851 and he arrived in Kilworth near London, Ontario with his parents, eight years later. T.J. Batman settled in Rockville, Manitoulin in 1877. He was reeve of Howland Township and helped negotiate bringing the railway to the island. Ruth Pettis mentions her grandfather, “A.J. Wagg was an astute businessman. Getting hydro and the railway to the island were two goals he shared as well.”

“Tom Martell: ‘Grandfather Ernest Martell cut lumber in the bush when he wasn’t working for the CPR. He cut wood for the ties when the railway tracks were being laid between Sudbury and Manitoulin. He said that the train was later nicknamed, ‘Agony Central’ attributed to the painfully slow ride because the train stopped for all passengers along the line, and stopped for all stations as well.”

Dick Wickenden: “Paternal grandparents, William, and Sarah (McNabb) Wickenden were the first of our family to live on Manitoulin, in Little Current. William worked for the ACR, the Algoma Central Railway. My father George was only three years old when his father died.” “William and his crew were trying to get water for the train at Victoria Mines while delivering a load of coal to Sudbury. The train staff was concerned about a possible cave-in on the tracks ahead. The train kept going. The accident happened at the next stop, Crane Hill Mine, when a steam-line broke and William was fatally injured.”

One can see that the trains had a significant role for the ancestors and people of Manitoulin, starting at the turn of the last century and beyond. Before roads were more commonly built and used, trains were a dependable source of transportation and a vital link between the north and the southern parts of Ontario. If the train to Little Current had been left in place, it could have served as a popular tourist venue, bringing people to the island in classic style, allowing gourmet meals to be enjoyed on board while guests could spend a few days on the Island and then return, enjoying another delicious meal on board. That would have been an enjoyable experience and a fine option for our beloved trains.