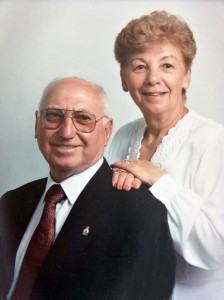

William Ross (Bud) McConnell is a charming gentleman, a newly awakened artist who cherishes historical perspectives. He is very proud to have shared most of his life with his beloved partner Dorothy. They had close to 62 years together. They endured the inconceivable hardship of losing three children, but always remained best friends, supporting each other through the hard times.

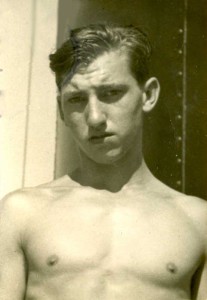

In his youth, during wartime, Bud had joined the merchant navy. He worked on three tankers and one passenger-cargo ship during his naval stint and he saw many foreign ports. Despite this historic and global perspective, he remains eminently happy to make his home on Manitoulin Island, not far from his son Barry, in Sheguiandah. “Barry is my rock,” Bud insists. “He does so much for me.”

“My paternal great-grandfather lived in Belfast. His son, my grandfather William McConnell, left Ireland during one of the famines. He became a blacksmith in Pennsylvania where my dad was born. Dad was three when he came to Canada with his family. My mother’s family came from Scotland.”

William Ross (Bud) was born to Jessie and William McConnell on March 6, 1928 in an old farmhouse. “I should have been called William as was tradition for a first son, but Bud stuck.” Bud would have two sisters and one brother. “My first memory is being immersed in the apple orchard on our farm. It was wonderful to climb those trees, sit undetected on a comfortable branch and eat fresh apples, mostly spy.” He also recalls early Christmas celebrations with the family. “We all got a bag of candy and we always had a good time.”

Another indelible memory established a convincing fear of snakes in a five-year-old. “My dad and the neighbours were haying. I was placed on top of a tree stump and hovered, terrified, as several snakes began to move up the sides of the stump towards me. My dad had to rescue me. This fear of snakes has never left me.”

Bud grew up on a small 49-acre farm just outside of Fenwick, about six miles from Welland. “We had two acres of garden that needed a lot of work. Dad grew grain and vegetables for our own use, with the help of a plow and a team of horses. He also had a contract with Niagara Falls in the 1930s to grow yellow string beans. We had to pick these endlessly because they never stopped growing. I hate them almost as much as the snakes.”

School was a one-room facility like most rural schools with seven grades and one teacher for 20 to 30 pupils. There was a pot-bellied stove that warmed the daily soup for all the children. “For some of the kids, this was a major meal. We all loved to stand beside the big aromatic pot, stir the soup and absorb the good smells.”

Bud left school at age 12 and began to work on the farm and do other paid work. The war created many shortages, including food. Age was not a limiting factor to get a job. “Workers were needed everywhere so if you could do the job, you got it.” His first job in the summer of 1940 was for Erie Peat near Port Colbourne. Bud cut and dried peat that was used in the operations of the Fort Erie Raceway. “I remember feeling proud to take my first week’s pay of four dollars to my mother. I was a contributing member of the household.” His next job was at Welland Machine and Tool, making aircraft wing struts for two years.

The winds of change blew for Bud. In the summer of 1943 he and three friends hitched a ride to Toronto to join the merchant navy. “My mum was ‘some disturbed’ but my dad said, ‘you’re growing up, stay out of trouble’.” Bud and his friends got on the train. They wound up in the shipping office in New York City. They called for five guys to come forward. “I put my hand up like my friends, but I wasn’t sitting near them and was not chosen for that ship. We had made a pact that we would stay together but fate had another role for me.”

“My ship went to Baltimore where a line of rollers were welded all around the toe-rail of the boat. A flexible hose was placed on the rollers and trailed out behind to refuel the naval escorts, the corvettes. In rough waters and it could take hours to find the end of the hose.” The ships left together from Halifax. It was neat to see the huge convoy suddenly change direction at a specific, pre-determined time.”

“On one foggy night a ship from another line hit us hard enough to cave in our side-plates. Luckily, the damage was above the water line so we could continue,” Bud shares. “I can still hear the resonating sound of depth charges, like a giant hammer on the hull, going off continually (underwater, to deter German U-boats) while we were in the convoy.” Bud wondered how the fleet could carry so many charges. “We came into Southampton two days after D-Day, June 6, 1944. All the roads to the docks were jammed with American trucks, waiting to be loaded and shipped to France.”

During two nights at sea in early 1945, their ship had left the convoy and was heading for Halifax. “A submarine’s conning-tower was spotted and we knew we had a problem. We began to run full out. Luckily, the water was rough with a large following wave. Apparently torpedoes don’t travel in a straight line in such conditions. The sub followed us for two days, likely waiting for the conditions to change. We had our survival suits on and hoped the wind would stay strong. The ship struggled with the prop coming out and then dropping back into the water with a great shudder but we made it home safely.”

Bud was home for shore leave for two spring days in 1945. His sister took him to an outdoor party where neighbours and friends perched on the grass while local talent performed. Pop was served and everyone had a good time. “That was the first time I met her friend, Dorothy June Clark. She was so beautiful, my heart fluttered. I thought I was having a heart attack,” Bud confesses, smiling. “It was really hard to return to the Fernbrook, a passenger-cargo ship in Boston harbour.”

“My fourth assignment was a passenger-cargo ship heading for Port Said, Egypt with four holds full of wheat. When we arrived at the port, the water at the docks was too shallow for the draft of our ship. A line of barges was stationed to unload the wheat. Planks were laid to connect the boats.”

“Shoeless men had to step through the hot tar that had been used to seal the steel deck plates. They were lowered into the dangerously hot hold so they could shovel the grain into sacks, which they did at a furious pace, despite the heat. About 200 men, looking for any kind of work, waited in line. They were all slight, wearing what seemed to be identical light flannel smocks that went to their ankles. They waited for their turn to have a 120-lb sack thrown on their back by two other men. The men carried the sacks along those planks to shore. It was quite a sight to see. This unloading took 13 days and continued around the clock.”

“We were allowed shore leave into a very restricted area where we were mobbed by kids of all ages wanting to sell an item or get something from us.” Just prior to leaving for home in August of 1945, the men heard an important announcement on the ship’s speaker. “War with Japan is over.” It was time for jubilance and celebration!

Bud was 17 in August of 1945, and his tender age was enough to get him out of the whaling ship duty he had agreed to earlier. He was most anxious to be reacquainted with his lovely young girlfriend Dorothy.

When he got home, his dad got him a job with his own employer, Atlas Steel in Welland. By October, Bud was working in the Booming Mill. They held the paperwork until his 18th birthday. “I learned all the jobs in the Bar Mill too. The cross-training came in handy.”

The Bar Mill, the 10.2 mill, was designed to roll many different shapes, round, octagonal, and flat bars. “The stainless steel bars you see as safety rails in elevators could have been made here,” Bud explains. “All grades of titanium and some super alloys were rolled here. Even uranium bars from the reactor were rolled here. Later I was told they used small tubes to store these rather than bars. It seems many men felt these uranium bars resulted in pain and early death. Many of these plants have been torn down since.”

Bud and Dorothy got happily reacquainted. They married on June 28, 1947 in Dorothy’s family dining room, accompanied by 30 guests. The honeymoon was spent at Weslemcoon Lake in the Peterborough area. They both loved to fish and sail and these pursuits further bonded their new relationship. They moved into an apartment and stayed until their first baby was on the way, then the couple moved into Bud’s parents’ home.

“My father gave us nine acres of land and we built a modest home there. After seven years, we bought some land and built another home in the Fonthill area. This home was special. It was designed by Dorothy and built into a hillside. The layout took advantage of the landscape, with exit doors at different levels.”

Bud continued to work at Atlas Steel. He volunteered to lead a Cub pack. Bud became a member of the Kinsmen Club and he joined a pipe band that travelled to various fairs and parades. “We got to each local town two to three times a year. Occasionally we got as far as New York or Ohio, so it kept us pretty busy.”

“We had lots of good times with the kids who loved to fish too. At one point we had three raccoons for pets. Barry saw their mother get hit by a car and soon after heard the cries of her babies. He followed the cries to a hole in a nearby tree and carefully pulled each tiny creature out through the hole. They were rolled up like little squirrels. Sadly a few died, but three survived and became family members. Son Kevin took one to the local fair and won first prize.”

Bud and his partner laid out and built the 18-hole 180-acre Highlands Course just outside of Welland. He and Dorothy were able to enjoy golfing there over the years until they sold it in 1971. “I hear the golf course is still doing very well,” Bud acknowledges.

The couple had five children. Their first child, Gail, had spina bifida. At that time there were no interventions and her anxious parents were told she would never walk. Sadly, she died at five months of age. Second son William was a breach birth and the doctor got to the delivery late, held up by a prior house call. The nurse did her very best, but unfortunately the baby had been without oxygen for too long and his brain was damaged.

Barry, the third child, became a ‘jack of all trades.’ He is good at various construction tasks, from drywall to tiling. He lives with his wife Laura in Sheguiandah. “Rory, our fourth child, is an excellent welder. He worked for John Deere near Welland.”

Fifth child Kevin was healthy, but at age five, his mother noticed that he was easily fatigued and they soon learned the terrible news: he had leukemia. “He was such a happy child when he was feeling good. He loved to fish. When he was 14 we were visiting Melody Bay, in Buckhorn (near Peterborough), when he began to feel very ill. He died before we could get him to the hospital in Peterborough.”

Both Barry and Rory worked with their dad in steel production at the rolling mill. Bud retired from Atlas Steel after 40 years on the job, at 58. “My favourite time of the year is fall. The leaves are amazing and that was the best time for the golf course. It was still a bright emerald green, wasn’t as crowded, the heat of summer had dissipated, and there were fewer bugs.”

The McConnells had a sailboat, a 25-foot MacGregor with a drop-keel. “On our first sailing trip from Port Colborne to Buffalo, we encountered a bad thunder storm that left Dorothy disillusioned with sailing. She did not relent until we got a bigger boat, a 29-foot Bayfield that made her feel safer. This cutter-rig was such a pleasure to sail.”

Friends Ann and Ed joined them when they decided to visit the Thousand Islands. They sailed from Port Colborne through the Welland Canal and laid-over at Niagara-on-the-Lake’s marina. “The next morning we left for Oswego on the American side and heard about some rough weather coming up. We were about six miles from Rochester when a five foot wave hit our beam and knocked the boat over. It righted again but a smaller boat in front of us did not fare well.”

“Ed noticed the boat in front of us had disappeared.” Bud saw some floating items nearby. “We headed over to find two young men on floating cushions. Their 24-foot boat had sunk.” Bud maneuvered their boat closer to the men and Ed, a tall man, easily flipped the two men onto their boat. The US Coast Guard was called and they asked them to stay in the area. They would send out a rescue ship.

“It was pitch black on the water, with lightning and high winds so we called the coast guard back to say we were coming in. They said their boat would be there shortly but it took another hour. When it did arrive it looked like a floating dock and I was afraid to get too close in rough water, so we both headed for shore.”

“We arrived to a small cheering crowd and an ambulance that took the two young men. It seems the two university students were going to sell their boat for school costs. I wondered if they would have survived if we hadn’t been nearby? To this day, I also wonder if they ever found their boat.” The two couples had good weather the next day with ‘following waves’ using only their storm jib. They got to Oswego in no time at all.

The couple enjoyed a seasonal lot and a trailer at Batman’s Campground at Sheguiandah. They spent some wonderful summers there. “We met so many great people who I still take pride in knowing.”

In 2000 Bud noticed a change in his wife. She was the family accountant and had a very sharp mind. “I noticed she missed some items that she would normally never have missed.” A CT scan did not show any problems, but by 2002 it was clear she had developed Alzheimer’s. She had lost one aunt to that disease.

The next three years were very stressful for Bud. “Thank God Barry was nearby when the going got rough. Sometimes she would want to go outside into the snow in her bare feet and there was nothing I could do to stop her. She seemed to have such strength. I called Barry and he would come over and help. In 2005 Dorothy was admitted to Lindhaven in St. Catharines, about 30 miles from home.

“Barry came to my rescue again. He was living in Sheguiandah on Manitoulin and he managed to get his mother into the Centennial Manor in the fall of 2006. He also had a room for me in his home.” In time Bud moved in with Dorothy at the Manor. Living with cancer and ankylosing spondylitis, an inflammation of the spinal joints causing pain and stiffness, Bud needed help too. With support, Bud and Dorothy had a few more good years together. “It was really difficult when she died in January of 2010. I was able to hold her when she passed away. Life just isn’t the same without her.”

Being an ardent historian is a comfort to Bud now. He has always been curious about innovation and life and he loves to read. Patience is another virtue. He has settled in well and his room is fully equipped. He has a computer. He can share email, read jokes and catch up on the news. His newfound hobby of painting has added enthusiasm to his life.

“Many of us here have started to paint with watercolours with the help of a few volunteers like Linda Jack, Lemar Hyatt, Beth Bond McCullagh and many others. I really enjoy it,” Bud states. He has created artful designs on several stools and a number of his works have been scooped up by admirers.

“I don’t have any regrets. If I could go back in time, there is nothing I would change. When I think of the amazing innovations that have occurred even in my short time, I am always incredulous. My home is here now in the Manor and I can’t say enough good about this place. The staff, my friends, the food and the entertainment make it a very special place to live out my days.”

“Although I am relatively new to this Island, I just love Manitoulin. It is such a laid-back place,” he sums up. “If you find yourself in a hurry, just relax and stop worrying. People just take things easy here and that is a good way to live your life. If you go downtown you are greeted with a warm ‘hello’ by friendly people. That makes life worthwhile. Manitoulin truly is a place aside from the rest of the world.”