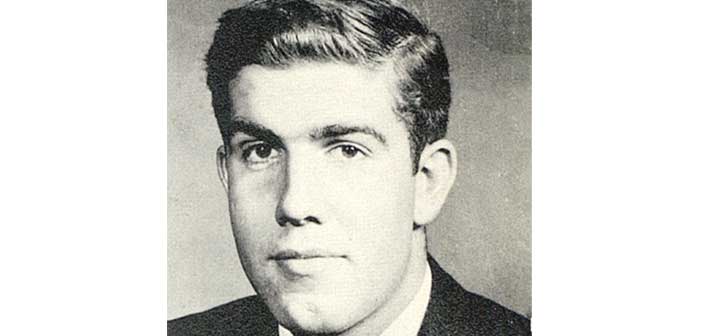

Joseph McBride Wilson

Joe Wilson hangs his hat at the Manitoulin Centennial Manor these days. He has had a very productive and exciting life that many may not be aware of. Joe grew up in the Swansea, High Park area, near the idyllic lakeside recreational area of Toronto known as Sunnyside. Before it faded out in the mid 1950s, Sunnyside was a mecca for Toronto sun seekers.

A book by Mike Filey called ‘I Remember Sunnyside’ sits on Joe’s desk. It provides a plethora of photos depicting visitors at the turn of the century, arriving in Model Ts, donning modest bathing attire, shooting the ‘chutes’ at the waterpark, watching horses dive from high platforms and touring the harbour area in steamboats. “I actually saw the horse dive into the water. It was really unusual,” Joe confirms. “That was my early life.” Joe looks back to this charming time with nostalgia.

As an adult, Joe spent much of his life abroad, having graduated with a Bachelor of Civil Engineering degree from the University of Akron in Ohio. He was involved with many major global projects, helping to construct large-scale water systems and other significant infrastructure in countries like Saudi Arabia and British Guiana. Here on Manitoulin, Joe helped with the Norisle and worked to enhance the Gore Bay docks, information centre and other waterfront buildings.

Joe was born to Arthur and Nettie (nee Watson) Wilson on January 20, 1930. He had an older brother, Jim, and would have a younger sister, Margaret. “My dad’s family came from England in the 1920s. My father was an electrical engineer who worked for Ontario Hydro, building the high voltage transmission system based in Niagara Falls.”

Joe was named after his uncle Joseph Watson who Joe attests was a ‘tough guy’ politician. Uncle Joe had worked for his maternal grandfather Fred Watson, well-known in the area. The Watsons owned the Hamilton Distillery. “My grandfather became associated with the Hiram Walker Distillery after the heyday of the temperance movement. He was also the mayor of Burlington for a time and assisted with building their water works established prior to the Second World War.

Young Joe lived close to the baseball stadium near High Park. Nearby was the armory where soldiers once staged a mock battle when he was about nine years old. “A few of us kids could be seen jumping around the riflemen who were shooting rubber bullets at each other. British airmen were training in the area too. Nobody seemed too concerned that a bunch of kids were disrupting the training or taking great risk just being there.”

“An early indelible memory was my mother showing me how to shoot a gun. She aimed safely away from the house and pulled the trigger. The bullet accidentally found a bird that fell from the tree, surprising both of us.” Joe tells us about the pumpkin pie his mother had made for him. “She told me afterwards that she had incorporated parsnips, which I hated with a passion. I never quite forgave her for tricking me like that.”

“Our family used to get into our dad’s Mercury Monterey and head for Burlington to see the Watson side of the family. I was proud of being a part of this wonderful estate situated on seven acres. The huge staircase with the heavy gleaming bannister became a terrific slide. An enormous den full of books and hunting photos also displayed mooseheads and guns on the walls.

Fred Watson hosted hunting parties with his cronies. His pointer and a Labrador retriever were both pets and well-trained hunting dogs. Grandfather Watson also raised guinea fowl and peacocks, beautiful birds with impressive fantails that they would display from time to time. The elder Watsons held elegant garden parties where all the guests donned their best attire.

Grandmother’s kitchen had a special drawer that was always filled with date turnovers. Outside, cherry, apple and peach trees were a delight for the 10 cousins and a few neighbours that regularly gathered. The creek that ran beside the house was a source of enjoyment too as was the playground area that included archery sites. “The adults could play tennis on three courts,” Joe reminisces. “After the war, the huge home with its enormous fireplace and dining room was torn down and replaced with a larger apartment building.”

“My grandparents were role models for me. They piqued my interest in creating projects and ultimately in engineering.” As a teen, Joe looked for construction work he could do to make money. “I darkened a lot of doorways until I got a job,” he shares. “Eventually, I helped build the grandstand on the CNE exhibition grounds. That job was my first big break into the construction world and it got me in front of a lot of influential people later.”

A younger cousin, ‘Joey’ Watson, got his first building job through Joe. “I was proud to see that he became a business manager and was later promoted to number two man in three different companies. He became a millionaire several times over. Another cousin, Bill Watson, got an MBA and had a similar career as a ‘money man’ working for big companies.”

Joe Wilson was doing well despite a medical condition that would affect him for much of his life. With hindsight he realized he was dealing with bipolar symptoms in the 1950s when there was no clear diagnosis or medication for this condition. “Luckily, my own doctor was one of the first to make lithium available for this psychological disorder. This helped control the symptoms.”

“My father died in 1946, at 46, of kidney disease. That was before dialysis. He had already lost the use of one kidney prior to this.” Joe, 16, was devastated and his whole life changed. “Even though he died so young, my father had instilled a good work ethic and sense of responsibility in my brother and me.”

His mother, sister and brother got work in Akron, Ohio and Joe joined them to go to university there. Joe’s post university CV describes him as being ‘six feet tall, and weighing 185 lbs’. It states that he would be ‘available for work in June 1954.’ After earning a Bachelor of Civil Engineering. Joe hoped to get work in engineering or construction.

His early academic and professional journey included being a member of the student council, social chairman of Lambda Chi Alpha, and member of the Sigma Tau Engineering Honorary Fraternity. Lastly, he had enjoyed intramural wrestling, freshman football and rowing. “I rowed and played football in high school at Western Technical, too. I was lucky to win two championships as the stroke man in eight man shells. The teams came in twos, fours and eights, each participant with a single oar. I was told our Argonaut Club team could have made the 1948 Summer Olympics if we had all stayed home.”

‘Employment experience’ cited cooperative work experience as a junior engineer at M. B. Guron and designer for Wilbur Watson and Associates in Ohio. He had also worked at Stone and Webster Corporation as a field engineer in Canada for the summer of 1950. His university cooperative work placements were only 18 hours a week so that left time for gainful employment.

“I was a night clerk for the popular Belmont Hotel in Cleveland, Ohio. Famous people like Debbie Reynolds stayed there, as well as all the members of the Ice Capades. The arena was right across the street. Hockey players were regular guests and the mafia who ran the hotel could be helpful when rounds were made. It was a very interesting job.”

After university, Joe got work with the sand, paving and aggregate business in Toronto. “I soon found I was more of a ‘hand-shaker’ than an engineer so I soon tired of this work and late in 1955, joined a big company, Alcan Aluminum, in British Guiana as an electrical engineer.

Earlier that year, Joe and his mother had gone to England to attend Joe’s brother’s wedding. They travelled elegantly on the Queen Elizabeth. It was also a chance to meet the kindly parents of Helen, his bride to be. Joe had been immediately attracted to his fiancée, an Irish beauty with distinctive auburn hair. Her parents lived and farmed in Ireland, producing eggs and dairy products. “We enjoyed the small town hospitality and the ambience of the narrow streets and stone buildings.”

Joe and his bride Mary Martha Anna Helpin, Helen, had set a wedding day for June 10, 1956 at the High Park United Church. That day had to be moved up to January 1, 1956 to fit Joe’s imminent reporting schedule in British Guiana for Alcan.

Their wedding and reception in Toronto was beautiful. The newlyweds honeymooned in a Collingwood cabin and then flew to Guiana to begin their life together. Joe wanted his bride to be happy. “As a good husband, after the wedding I used the garage to smoke my cigars and later my pipe. Helen and I lived in the Alcan community of 10,000 people.”

“The snakes were huge in that part of the world,” Joe recalls as he shares a photo of one such reptile. He is holding the head and seven others are grasping the body. “Alcan had a hunting camp 22 miles into the jungle. A fisherman found the boa constrictor as it was cooling itself among some boxes. They put it in a big metal box and fed it chickens and frogs but the snake didn’t eat them. Eventually it had to be shot and we all held it for a photo.”

His bride Helen was gifted with a three-toed sloth on her birthday. It had a festive ribbon around its neck. Of course, it was later released. Nobody was sure how to deal with such a gift.

“I liked the Alcan job in Guiana because we oversaw the work from start to finish. The huge structures for aluminum production arose where nothing was before.” Alcan had worked at a smaller capacity, in a nearby area, right through the war years. There were stories of German submarines coming into the mouth of the river nearby.

In the late 1950s Joe and his family moved back to North York outside of Toronto, where Joe was in charge of setting up new buildings for oxygen and nitrogen production. “We lived in an old home that I enhanced with a huge beam from EP Taylor’s barn. It was a great addition to our own remodelling phase.”

In 1961 Joe and Helen and their two kids were back in the States, working for the Lummus Company in Newark, New Jersey. In time, Joe became president of the American Society of Civil Engineers and treasurer of the Ohio Association of Professional Engineers.

In 1963 Joe was back in Hamilton as construction superintendent on a six month project. The Hamilton oxygen and nitrogen plant completed in October of 1963 and at that time Joe had to return to the States or his work visa would not be reinstated. He was reassigned to the Newark office of Lummus Co. In between jobs, Joe did a short stint in the World Trade Centre where he made some excellent contacts. Another commission took him to Jordan to create infrastructure for a 10,000-strong community. “We built a water facility for them as well as other needed buildings.

In 1964 Joe and his family moved to Kansas where the engineer built a helium liquefaction company. He hired all the staff to construct the German-designed facility, the largest of its kind in the world at that time, producing 180 million cubic feet per year.

“You separate the helium from the natural gas and then you liquefy it at a cold temperature. The helium was used mainly by welding companies, Atomic Energy, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration groups.”

The family rented a house for a year for that project. “Helen knew friends of her father here, so she was happy. The kids could walk to school.” Sightseeing was on the agenda too. Joe and Helen took the kids through a local well-known fort. Mike, about 10, was thrilled to be led down the tunnel that was used to spy on the exterior of the fort. The settlers and the military could check to see if anyone was sneaking up.”

Joe Wilson and his family spent five years in Timmins where he engineered twenty million dollars in construction including an IGA store, a Canadian Tire, two senior centers and a mall. Then it was on to Fort Albany First Nation where he supervised $10,000,000 worth of construction. Joe raised all the money for this project, which included a sewer and water system with a processing plant, major dyke protection program, a new grade school and high school, a police station, clinic and senior centre and other structures. This job was one of his last projects.

The couple’s two children were Michael and Lise. Michael had difficulty with the discipline of schoolwork but he liked theatre. Sadly, he suffered with mental health issues and died while in his 20s. Joe, in Saudi Arabia at the time, was heartbroken. Lise was married with two children of her own. She became an executive for Dell Computers but died in her 40s. Joe and Helen later decided to end their marriage.

By the 1990s, Joe had met Christine and he began to work on the waterfront in Gore Bay. He had been stationed in Sault St. Marie putting in a new sewage and water intake system. He went through manpower looking for divers and found out that Gore Bay was looking for someone for their waterfront.

“I was inspired by the Chesapeake Lighthouse with its three-story turret when I designed the Gore Bay information centre.” The talented engineer also designed a small business center, the building that was originally a fish hatchery. Today this center houses a beautiful art gallery with studios for several Manitoulin artists: the Ravenseyrie and Fish Point Studios. Another building he designed would be used for boat-building.

While on Manitoulin, Joe and Christine rented and lived in the Meldrum Bay lighthouse for a while. Joe got a fishing boat which he modified to include a cabin on the back. “We wanted to enjoy some of Manitoulin’s fine waterways and fish too, while working on the Gore Bay docks.” Joe also worked on the Norisle using designs he had completed a decade earlier.

Manitoulin held out the potential for more work of a specialized nature. In April of 1999 Joe and his partner had a serious car accident that sent her to the hospital for jaw reconstruction and plastic surgery, broken ribs, cuts and bruises. Joe sustained lacerations across the forehead and a crushed lumbar disc requiring two horizontal rods in his spine. Joe was very thankful to the hospital staff, the police, and the ambulance for their fine work. Sadly this accident was a real setback for Joe.

Today, fifteen years later, when asked about his strengths, he felt that he became adept at assessing the broad scope of a project and applying his knowledge to get the job done. “A systematic approach to tackling a legal issue is something I can now claim to have experience with too. Dealing with medical issues my partner and I sustained was quite a task,” he acknowledges. Then he pauses and smiles, “I was pretty good at rowing in school.”

Today, Joe hangs his hat at the Manitoulin Centennial Manor. He arrived about four and a half years ago. Christine visited him in the Manor regularly until she died a few years ago. Today Joe is dealing with medical issues including Parkinson’s, prostate and colon cancer along with his long-standing bi-polar condition. He is on continuous oxygen and spends much time in his wheelchair. Despite this, he still manages boxes of files stored in his room here; all that is left from his once-active life. His sister Margaret comes once a year to visit her brother.

Margaret is a retired teacher. Joe’s brother Jim became a businessman, an entrepreneur with his own sailboat and a golf course. He also owned a business that installed institutional sprinkler systems. “Jim bought our parent’s home in Swansea. My dad had paid $8,000 for it in the 1930s and about five years ago, sold the house for $180,000.” He was a smoker and sadly he died trying to smoke while hooked up to an oxygen tank.

As was his habit as an engineer, Joe continues to log daily events as he has always done. He still enjoys wonderful memories of his life with his childhood family as well as with his own spouse and children and his last partner Christine. “Helen and I were a family of gypsies with all the travelling we did.”

Memories began in Sunnyside in Toronto, and grew to include Guiana, Saudi Arabia, Hamilton, Timmins and Manitoulin Island. “On Manitoulin, we find a microcosm of a coastal fishing village with farming, tourism and lumbering.”

Few of us have lived the life Joe has. Now he is choosing to spend his last years here. “I was lucky I was at the Manor when my lungs needed oxygen. People have been good to me. I found both work and a good lifestyle here. At this point, I really don’t have anything else to lose and I am very happy to be here on this Island of Manitoulin.”