William Blair Sullivan

William Blair Sullivan kept an excellent diary of his history and his personal years as a World War Two soldier. Excerpts are included here.

Blair began his life on the wind-swept prairies and spent much of his adult life in the United States, serving in the American army during World War Two and enjoying a fruitful teaching profession before he retired to Providence Bay with his wife Lillian.

“My paternal great-grandfather, James William Sullivan, was born in Rigdon, Indiana in 1854. He and his wife Eunice farmed 180 acres. In 1876, William moved his family to Kansas to a new homestead. Cattle and horses walked with them; household articles came by wagon. They farmed on virgin prairie and hunted antelope or deer for meat.”

“One morning, my grandmother was horrified to see a rattlesnake hanging over her son’s cradle. It had come right through the sod roof. Terror was displaced by anger and the snake met a quick demise. The family returned to Indiana where six more siblings were born,” Blair reflects. “Had they stayed, they might have struck it rich as this part of Kansas was to become a major oil-producing area.”

Paternal grandfather Paul, the oldest in his family, married Claudia Jones in 1902. He taught at a one-room school called ‘Dead Dog’ near Rigdon. Paul and Claudia would have three sons. Their first, Gerald, born in 1903, would become Blair’s father. In 1910, when Saskatchewan became a province, flyers welcoming new settlers were sent throughout Canada and the American Mid-West.

Paul and his family moved to Drinkwater, Saskatchewan, 15 miles south of Moose Jaw. They had been enticed by the opportunity to own ‘tree-less’ prairie land. Paul built stockyards for farmers and Gerald helped. Soon drought, grasshoppers, gophers, windstorms, severe winters and very little money became familiar to the new Canadians. After a fire destroyed most of their possessions, they moved to a new community where Paul farmed and taught school.

In 1892, maternal grandfather George Campbell left Staynor, near Collingwood in southern Ontario, and arrived, by boat, to Michael’s Bay, on Manitoulin Island’s south shore, a sawmilling community of several hundred members. George worked in the lumber industry for a Mr. Mutchmore. He also helped to build the 18-mile road to Providence Bay over three winters. George bought 50 acres of woodland north of Providence Bay and cleared the land with two oxen. George married Mamie McAllister in 1903. The two-storied home he built still stands on the Harold Arnold farm.

In 1918, George got a written invitation from a former Manitoulin neighbour, now living in Saskatchewan. The neighbour sent two five dollar bills for a trip to and from Drinkwater, Saskatchewan. George took the train west to help with his friend’s wheat harvest in 1918. The Homesteader’s Act required the donated 30 acres to be under crop after the first year, so it could be registered and the applicant could ask for another quarter of land.

George soon felt inspired to move his family where he felt the future lay. After a family conference, the move was planned and the Manitoulin farm was sold. It was March 1920 when two parents, five children and two of George’s brothers walked with the horses and cattle to Little Current. Turkeys were in cages and their household items were packed on four skids. It took three days to get there, sustained by a neighbour’s parting gift of three flour bags, replete with fresh bread.

In Little Current, five boxcars were filled with tools, cattle, horses and household goods. The train stopped daily so the animals could be watered and fed, aided by railway staff. The Campbells arrived in Moose Jaw five days later and began their new life on the prairies, farming in the Cardross area, across the road from the Sullivans.

“My parents Gerald and Anna (Campbell) Sullivan were married in 1922 on the same day Gerald’s brother and Anna’s sister also married. Gerald built a house and a garage with a filling station and began a farm-implement dealership where the CNR line ended in Cardross. Moose Jaw was 54 miles away. Cardross residents came to depend on the twice-weekly train for visitors, gas, grain seeds, mail and other goods. All the gas and oil arrived in 44 gallon barrels. The filling station had an underground tank and an upper glass tank. Gas sold for under 20 cents a gallon. Gerald also cut hair on Saturday night when everyone collected in town after a regular train delivery.

Blair was born on September 2, 1924. It was a difficult birth attended by their doctor who had been summoned from town. Blair would have no siblings. An early memory was snagging gophers with binder twine when their heads popped up. Farmers’ crops were being destroyed by these little creatures. “Tails were redeemed at a penny apiece.”

“Grade 1 was in a single-room school house with eight rows of ‘boxcars’ (desks). In the summer, when the grain was higher and pupils were forbidden from walking through the crops it was a three mile trip. In winter, as the crow flies, you could ski a mile and a half to get there. There were three of us in Grade 1. I remember Willie taking my new pocket knife from my desk. I pounced on the thief and wrestled it back but the teacher spotted us and we both got the strap.” Both Willie and teacher Mary Blair’s became friends over the years. “I said goodbye to Mary just before she died in a nursing home in Moose Jaw in 1986.”

“Coal was free for the taking. A frozen lake allowed easier removal of two tons of coal using two horses and a sleigh. Once, my father and uncle ran into a blizzard at minus 54°F. They became disorientated, unhitched their horses and followed their animals home. Mother heard a bang and opened the door to a blanket-covered horse head staring at her. They were all lucky to be alive.”

“In 1935, our family moved to Regina where dad got a job with General Motors, driving cars off the assembly line.” The plant closed during the depression. When the war started in 1939, the family moved to Rigdon, Indiana, two miles from grandfather Sullivan’s farm. Gerald husked corn for 75 cents a day before he was hired as a night watchman for GM. Rabbits were hunted for meat and supplemented with an occasional pig from grandfather’s farm.

Blair’s family moved a few times before they settled in Alexandria, where the teen attended high school and joined the varsity football team. In May of 1942, Blair met Lillian Alice Orme. “I had been taken to her home by a friend to buy a schoolbook. As soon as I saw her, I knew she would become much more important to me than that book I came for.” Later Blair learned that she had felt the same way.

“At Christmas of 1942 my father took me to Windsor so I could enlist in the Canadian Air Force. I filled in the paperwork, passed the physical and was asked to report for training after graduating from Alexandria High School in June 1943.” Before Blair could report to the RCAF, the US Army conscripted him. After basic training at Camp Roberts, the young recruit was given three options: remain in the 500-man battalion and ship out to the Pacific; attend officer training school at Fort Still or enter an Army Specialized Training Program as a pre-engineering cadet at Stanford University. “I chose the last option.” Only six of 500 recruits were heading to Stanford.

Later in 1943, as the war progressed, Blair transferred back to Indiana University. On weekends, the young student could visit his family and Lillian who was doing nursing training at Indiana Medical School campus. “Lillian’s dad operated the Standard Oil Company bulk station so we were able to get added gas stamps despite the rationing.”

In January of 1943, America was pressured to add infantry to the war. The school program was halted and Blair joined his peers at Camp Shelby, a huge army base. He was assigned to the 516th field Artillery Battalion, to work in the ‘Survey and Forward Recognisance Squad.’ “I remember trying to impress the boys one day while running a survey line. I was confronted with a creek while carrying a large pole so decided to try pole-vaulting. Mid-creek, I found myself face-to-face with a water moccasin snake, mouth wide-open, ready to strike. I leapt away, simultaneously thrashing the water, and escaped the attack.” His buddies were bent over laughing.

After training, Blair, now nicknamed Sully, headed for New York with his cohort for final processing prior to getting ready to be shipped to Europe. Over 20,000 men and 600 nurses boarded the Aquitania, a sister ship to the Titanic. “We were assigned hammocks outside.” The ship zig-zagged across the ocean in a south-east direction heading north along the shore of Ireland and Scotland where they anchored six days later.

The men boarded southbound trains at dusk to escape bombing; they were cheered by children who had been evacuated from London to safety. “The children chanted ‘gum chum’ and we threw them gum. We took over evacuated homes in Broadstone on the English Channel. Two months later, we got our marching orders for France.”

Blair wound up on LST (Landing Ship Tank) number 350 headed for the Seine River near Rouen, France. The men and twelve ‘155 mm’ guns landed on the river’s edge and regrouped in a field. They stopped at Nolleval France for 10 days in the rain and were surprised at the anger they encountered from locals. “We were upset because we felt we were helping them. We never really found out why they were angry.”

Later in December 1944, the 516th marched to Cambrai which had a walled inner city built by the Romans. Marching to Belgium, they found many dead horses and destroyed vehicles. On December 16 the Battle of the Bulge against Germany was launched and the 516th battalion became part of the 9th army under the command of British General Montgomery.

“We came to the front lines near Palenberg, Germany where gun crews were firing at enemy targets. The roar of twelve ‘155 mm’ guns firing at once was deafening. We established an observation post in a bombed house, a mile away, to assess the status of our targets.” Christmas Eve was spent in a stone building with a partial moat. On Christmas day the men enjoyed a hot meal but were strafed by a ME 109 and had to dive for cover. Nobody was hurt, but a Christmas cake sent by family was blown off the hood of the truck.

The next morning Blair helped run a survey for the new gun positions. He was hit by mortars but only the rear of the truck got the shrapnel. B17s were bombing the industrial Ruhr area. Occasionally one would be shot down and we would see a parachute emerge. In January 1945, Blair and his survey team were establishing observation points. “I was standing in a doorway when debris hit my head. I realized someone was shooting at me but the rounds hit high. I dropped to the ground and the shooting stopped.”

“The most deadly encounter saw the Germans shooting OK-bazookas at American and British tanks. The tanks just exploded and there were many casualties. It was a terrifying scene for the men of the 516th battalion. All the American and British soldiers had been killed and the half-tracks and Sherman tanks destroyed. Eventually the remaining German soldiers were killed or crushed in their dug holes where they had been hiding.”

Blair, on a German motorcycle, was one of the first to cross the Rhine River on a pontoon bridge that the men had built. Sherman Tanks followed. On the other side they found complete destruction as they moved forward, sheltering in basements overnight. “On April 12, we found a forced labour concentration camp in Melle. The desperate Russian and Polish people rushed towards us. We only had one soldier who could converse with them, in German. They were overjoyed. We found out that they had been there for years. Food was brought in and then the freed captives were put on trains bound for the Ukraine. The women had tied lilacs to some of the box cars in celebration. It was quite a scene.”

On May 8, the war ended and the men were in the town of Halle, controlled by the British Army. It was a joyous day and celebrations were potent. A factory in Backnang became a temporary home. “We worked with local people, giving them coffee in return for a good meal. Blair and a buddy found a Mercedes hidden in a haystack, reportedly left by an SS officer. The two men brought gas, an air pump for the tires and a new battery. Their joy was short-lived because the keys were soon requested by their commanding officer. Travelling celebrities helped substitute for the missing car rides. The men enjoyed shows by Jack Benny, Betty Hutton and other travelling stars.

It took a while to get men of the armed forces back home. Some remained in camps in France until February 1946. Those with the most combat time and months of service had more points and were taken home first. “I was the only Canadian out in 1946. Our cohort arrived to Long Island on March 6. There wasn’t a dry eye when the Statue of Liberty came into sight. The joy of coming home mingled with the pain of realization that so many of our fellow soldiers could not enjoy this moment.”

Blair was joyfully welcomed home by his father, mother, Lillian and other family members. He soon learned he had 42 months of prepaid university waiting for him, so he applied for forestry. His father had a friend in the US Congress who helped him get into that program at Ball State University in Indiana.”

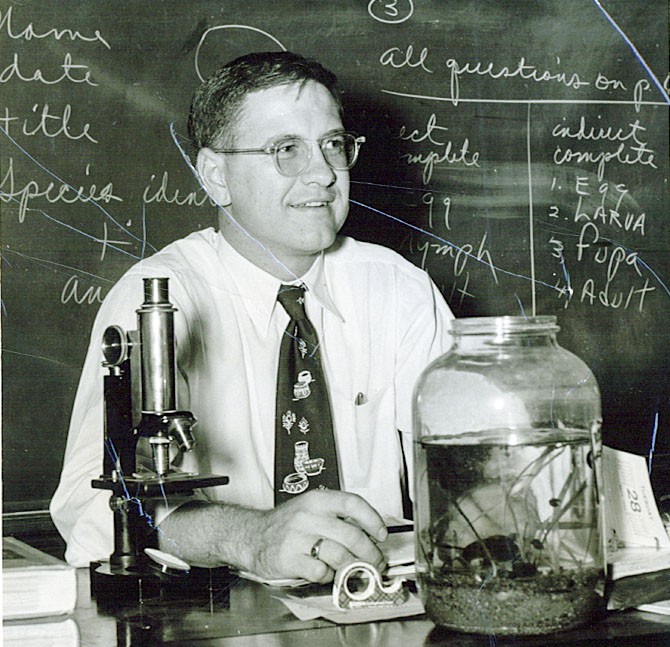

Lilian and Blair married on July 21. 1946. After graduating in 1955, Blair became a high school biology teacher. He became vice-principal after 11 years and principal for 16 more years. The young teacher was asked to be a PhD candidate at Purdue but his professor died tragically in a car accident and Blair decided not to pursue the program. He became a 30-year member of the Presbyterian Church and, in 1948, joined the Masonic Lodge. Lillian got her Masters degree in psychometrics and worked in the public school system.

The couple had two children, Ann and Blair Paul. Ann is now retired from her high school teaching job in North Bay. She is active in the Catholic Church and helps to take care of retired nuns. There are three grandchildren: Ben Oakes is Ann’s son. He works for a British tobacco company. Megan and Shannon are Blair and Jenny’s daughters. Shannon is an Olympic swimmer and is finishing her second year of veterinary medicine training. Megan has a degree in foreign languages and business.

In 1950, Blair and Lillian came for a visit to Manitoulin. “We loved my ancestral Providence Bay, and decided this would be a great place spend our summer and ultimately retire.” They bought some land on the water and built two camps on the shore, aptly named Sullivan’s Cottages. An A-frame was added in 1970. We also fixed up the old town jail in Providence Bay. Singer Jane Siberry stayed in one of the cottages with a friend and the Sullivans got to know the talented young singer. Two young Australian ladies stayed ‘in-jail’ for a month as well.”

“In 1979, we retired to Manitoulin, living in the jail ourselves, until the A-frame renovations were done. My parents moved into a house in town we had purchased 10 years earlier. Unfortunately, my father died within a year.” Blair and Lillian also kept a home in Arizona for 20 years.

“Lillian continued with psychometrics, working with RN Glen Hallet. I spent many good hours helping set up the information display and teach students at the Providence Bay Interpretive Center,” Blair offers. “In 1985, for our 40th anniversary, Lillian and I visited England, France, Belgium, Holland, Germany, Austria, Switzerland and Luxemburg. We met a couple in Germany that had researched the American Ninth Army. We also noticed that many rebuilt houses had “tile” roofs made of spent shell casings that had been cut in half lengthwise.”

“The most important events in my life were the birth of my daughter and my son. Lillian was awake for our son’s birth and it was an outstanding experience for me as was coming home with 5,000 troops, being met by two escort ships shooting streams of water over us, a waiting band, and the Statue of Liberty behind us.”

“Generally, I am in good health, apart from my bad hearing. I don’t have much to complain about. Sadly, Lillian passed away two years ago. “We were married for 65 years and I miss her.” Blair wears her wedding ring on his little finger, next to his ring. “Each day I thank the Lord for giving me another day,” he shares. “I am planning a trip with my son to attend my granddaughter’s Megan’s wedding and another to see the Pacific Northwest where Lewis and Clark were explorers. It will include a paddle wheeler trip aboard ‘The Queen of the West’.”

“Manitoulin is the cleanest, most tranquil place I know. In the summer, you can see the wildlife in its original habitat. We have pure water and fewer big problems compared to the city. Help is close at hand. Two years ago, when I had some heart trouble, I pushed a button on my Phillips Lifeline and my neighbour Rick Hibna was here in no time with the ambulance. Murray McDermid and I can call each other too, if either need help. I really can’t ask for anything more. After the heart-wrenching drama of WW Two, this really is an ideal place to spend my remaining years.”