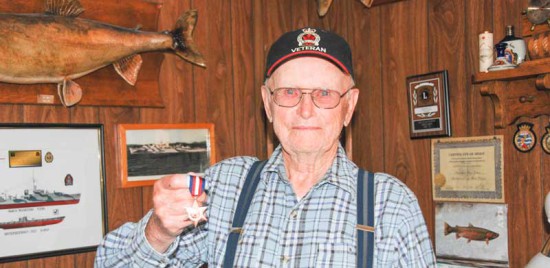

MINDEMOYA—Allan and Alma Tustian were busy entertaining on their sunny back deck recently when this reporter popped by to snap a photo of Mr. Tustian for the cover of the new Big Red Phonebook (yes, it is coming) when he shared his latest hardware with his guests.

“It just arrived,” he smiles, charming as always.

Disappearing to his room lined with merchant marine photos and acknowledgements for just about everything—from the Central Manitoulin Lions Club (Mr. Tustian is a charter member) to a lifesaving recognition from the 1940s—he reappears to show his guests the Arctic Star.

The Arctic Star is a United Kingdom campaign medal, awarded to those who participated in any length of service above the Arctic Circle in either the Navy or the Armed Forces, specifically in the Arctic convoys of WWII.

“You’re running out of room, Allan, I don’t know where you’re going to put it,” Alma Tustian says, pointing to her husband’s Legion jacket brimming with medals.

Mr. Tustian said he was alerted to the medal, which the United Kingdom announced in 2012, by R.L. Duane Duff, author of ‘Waskesiu: Canada’s First Frigate.’ The nanogenarian was a radar operator, and a navigator yeoman, aboard the Waskesiu.

“I wrote a letter to the British government and told them about my service,” he explained. “I got a letter back saying that there were a lot of people sending for it, but two weeks later it arrived in the mail.”

Mr. Tustian explained that the Waskesiu was part of a convoy made up of five destroyers and frigates known collectively as the EG6. “We were supposed to just be hunting submarines, but just before D-Day we were designated to take a convoy into Murmansk, Russia,” he said. Murmansk is the largest city above the Arctic Circle.

Murmansk was a link to the West for Russia during WWII, with supplies for Russia’s military efforts brought to the city through Arctic convoys.

German forces in Finnish territory launched an offensive against the city in 1941 as part of Operation Silver Fox, and Murmansk suffered extensive destruction, the magnitude of which was rivaled only by the destruction of Leningrad and Stalingrad. However, fierce Soviet resistance and harsh local weather conditions prevented the Germans from capturing the city and cutting off the vital Karelian railway line and the ice-free harbour, according to one online source.

For the rest of the war, Murmansk served as a transit point for weapons and other supplies entering the Soviet Union from other Allied nations. It was this resistance that was commemorated at the 40th anniversary of the victory over the Germans in the formal designation of Murmansk as a Hero City on May 6, 1985.

“It was a dangerous trip, cold, and the submarines were pretty plentiful,” Mr. Tustian allowed. “They (German submarines) were sinking ships the whole way up. We were taking equipment up to the Russians to beat the Nazis. The Allies brought oil, ships and gave them a cruiser (a type of warship).” As the crew of that cruiser didn’t want to stick around above the Arctic Circle, they came back with the convoy.

“We made the trip okay,” he continued, “and spent 10 days in a little settlement just outside of Murmansk. It was just a little hamlet, like Mindemoya, with log houses and one brick building—the hospital.”

The sailors were warned upon arrival to stay away from the Russian women, as if they were caught fraternizing with the men, they would be quickly sent to the front lines as punishment.

Mr. Tustian recalled exchanges with the Russian soldiers, including trading his wool sweater in exchange for a Russian knife. While stripping off his sweater, someone came upon the exchange, which made the Russians beat a hasty retreat, leaving behind the knife. Mr. Tustian got to keep both his sweater and the knife. The knife was eventually stolen from him, however. Another encounter saw himself and a fellow sailor taking a walk through the town. While cresting a hill, below them they saw a fearsome sight of miles of men marching. They guessed the men were prisoners and left before they were spotted.

“It was an important thing that happened (the convoy) because the Russians were being beaten badly and needed our help,” he added.

Ten days later, the convoy left Murmansk, zigzagging as they went, being careful to never travel in a straight line to keep the submarines guessing.

“We were almost torpedoed on the way home,” Mr. Tustian explained. “The Germans had developed an acoustic torpedo that followed sound. The Canadians had developed a line, the catline, which was streamed 50 yards behind the Waskesiu that made more noise than a propeller.”

Within no time of using the new Canadian invention, the Germans found their ‘target’ and blew up the Waskesiu’s catline. It had done its job.

The Waskesiu then headed for Ireland, and then on to England where it anchored, waiting for the D-Day invasion. While in England, Mr. Tustian was late for an outing to shore with his shipmates, having to go in with the officers instead. Walking the beach by himself, he came across two sisters and their dog that was being swept away by the waves. Rescuing the dog, Mr. Tustian was immediately welcomed into their home where the sisters cooked for him and fussed over him “while the rest were getting drunk.” He kept in touch with one of the sisters until her recent passing.

When D-Day came, the Waskesiu lined up with other warships end to end in the Bay of Biscayne, preventing the Germans from getting through.

The UK Arctic Star is actually Mr. Tustian’s second acknowledgment of that convoy, having received the Russian Medal of Ushakov, that country’s version of the Arctic Star some years earlier.

Mr. Tustian served the longest period of his time in the Canadian Navy with the Waskesiu over any other vessel and the frigate holds a special place in his heart. The frigate also holds the special recognition of being the first Canadian vessel to sink a German submarine, with Mr. Tustian manning the radar at the time. All who could be rescued were taken aboard the Waskesiu and later transported to prisoner of war camps in Canada. Decades later, the Tustians and other Waskesiu veterans had the opportunity to meet one of those German prisoners of war at a reunion near Kingston.