LITTLE CURRENT—The strong winds that greeted the small but hardy band attending the unveiling of a memorial plaque recognizing Little Current Asia survivor Duncan Tinkus, who was just 17 when the ill-fated vessel went down in a fierce gale coming from Collingwood, Canada’s worst maritime disaster. The gathering included Tinkus family descendant Judy McKay and her daughters Linda Reid and Lorie Gill, as well as Great Lakes history enthusiast Fred Holmes, who instigated (and financed) the effort to have commemorative plaques installed.

“The Asia was Canada’s Titanic,” explained commemoration organizer JoAnne Pilon. “A traumatic event for a young country going through the throes of nation building. Many women and children lost their lives. There were not enough lifeboats, warning signs were missed, mistakes made, and there were survivors. Because there were survivors, we know what those on board endured.”

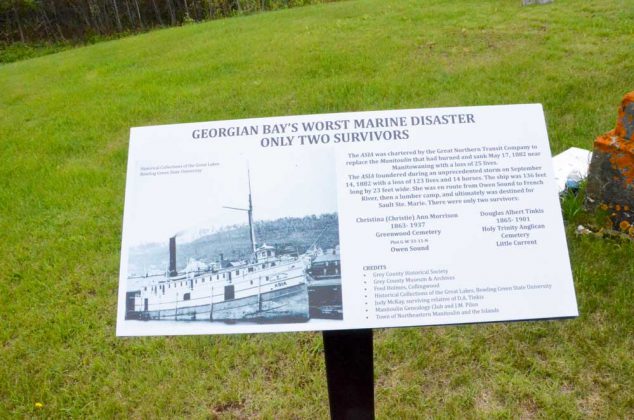

Ms. Pilon noted that the Asia sunk on September 14, 1882 and 123 lives were lost when she went down. The only two survivors were Duncan Tinkus, age 17, and Christy Ann Morrison, age 19. Mr. Tinkus went on to live only to the age of 37, although he never married, he went on to become quite a successful businessman. He was buried in the Holy Trinity Anglican cemetery on the edge of Little Current, where the historical plaque was unveiled on Monday.

Ms. Morrison lived much longer, to age 72, and is buried in Owen Sound’s Greenwood Cemetery. Her husband was Albert Fleming.

The plaque is installed beside the Tinkus family monument and lists a Collin Ross Tinkus who fell in action on October 26, 1917 at Ypres in Belgium; a Jehiel Tinkus, the son of United Empire Loyalists who died in 1900 and whose sons built what is now the Anchor Inn in 1888; and Angeline McMullen, Jehiel’s wife who died in 1906, although no engraving on the monument marks her passing. James Herman Tinkus, Duncan’s uncle, died aboard the Asia at age 37. His body was never recovered.

Local history enthusiast Bill Caesar gave a brief history of the Asia, noting that she was a replacement for the Manitoulin which had run aground and been destroyed. The Great Northern Transit Company found a vessel built for canal work in the Niagara-on-the-Lake region, totally unsuited to service in the less protected waters of Georgian Bay.

With far too high a superstructure, complicated by the heaping of cargo on the upper deck (including horses and cattle) and 120 passengers for which there were far too few lifeboats, the vessel was a floating deathtrap when placed on the violent waves of a Georgian Bay storm. Only one of the lifeboats was not made of wood and the violent waves smashed the wooden ones into pieces. Her engines were incapable of keeping the ship’s nose into the waves and she wallowed helplessly in the troughs, eventually succumbing to the storm.

“The chaos and panic must have been unbelievable,” said Mr. Caesar, quoting from the book on shipwrecks he has authored. “Several people, including the captain, managed to escape in the last remaining lifeboat, but even it was repeatedly capsized and they were left struggling in the raging seas. By morning only two had survived.”

The pair were eventually washed ashore near French River where they were rescued by a Native family in a sailboat.

The Asia was 132 feet long, 350 tons and built in St. Catharines. It was Captain John Savage’s first command.

The Asia has never been found.

The Manitoulin was eventually raised, rebuilt and renamed the Atlantic, but she only lasted in service for a few years before running aground on rocks and being burned to a total loss.

There was some good to come out of Canada’s worst maritime tragedy, however. Following the inquest the government was forced to implement three programs including: more stringent regulations for certification of skippers and improved lifesaving equipment for ships, an extensive lighthouse construction program and a survey of Georgian Bay by Royal Navy Staff Commander Boulton—many of his charts remain in use.

Mr. Caesar also related the tragic story of two young Jewish boys who had fled conscription (and almost certain death) in the Russian Czar’s army. Unable to speak English, they were known to the other passengers only as “the strangers.” After crossing much of Europe, a six-to-10-week Atlantic voyage on an over-crowded sailing ship and making their way by rail to Collingwood they were headed into the vast wilderness of New Ontario to find work as lumberjacks.

“I can only imagine the family back home waiting for a letter,” said Mr. Caesar. “A letter telling their family of the adventures in their new lives, that they had met girls and married, that they were sending money home for the others to join them. It was a letter that would never come.”

Mr. Caesar related Mr. Tinkus’ testimony at the inquest to illuminate the horror faced by the passengers and crew of the Asia as she foundered.

“The first to succumb was one of the strangers. The poor fellow made an effort to retain his hold on life, but he had to let go. About two hours afterwards, the other stranger followed him, and was laid in the bottom of the boat by the side of his dead comrade.”

Countless waves pounded those helpless in the boat, with only a single paddle to attempt to direct its course, until only two people remained alive.

Ms. McKay and Ms. Pilon unveiled the commemorative plaque following the presentations and Ms. Pilon presented both Ms. McKay and Northeast Town Mayor Al MacNevin with copies of the plaque, one for the family and the other for display at the Centennial Museum of Sheguiandah.

“This was fantastic,” said Ms. McKay following the ceremonies. “It was truly wonderful to see this taking place and the sinking being recognized so long after it happened.”

The group then retired to the Anchor Inn where they were treated to a roast beef dinner by Mr. Holmes. The dinner was based on a third class passenger’s menu from the Titanic. “I couldn’t find a copy of a Great Lakes dinner menu,” laughed Ms. Pilon.

Plans are in place to have a similar commemoration in place for Ms. Morrison in Owen Sound.