AUNDECK OMNI KANING—In a poignant gathering at the 4 Directions Centre, a group of women came together for a night of solemn remembrance, marking the 34th anniversary of the tragic murder of 14 young women at Polytechnique Montréal on December 6, 1989. This heinous act of violent misogyny shook the nation and spurred Parliament to designate this day as the National Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence Against Women.

Traditionally observed with candlelight vigils honoring the lives lost—Genevièver Bergeron, Hélène Colgan, Nathalie Croteu, Barbara Daigneault, Anne-Marie Edward, Maud Haviernick, Maryse Laganière, Maryse Lecair, Anne-Marie Lemay, Sonia Pelletier, Michèle Richard, Annie St-Arneault, Annie Turcotte and Barbara Klucznik-Widajewics—this year’s event took a different direction. Families of the victims expressed a desire for a shift towards education and engagement regarding gender-based violence (GBV), as shared by Colleen Hill, executive director of Manitoulin Family Services.

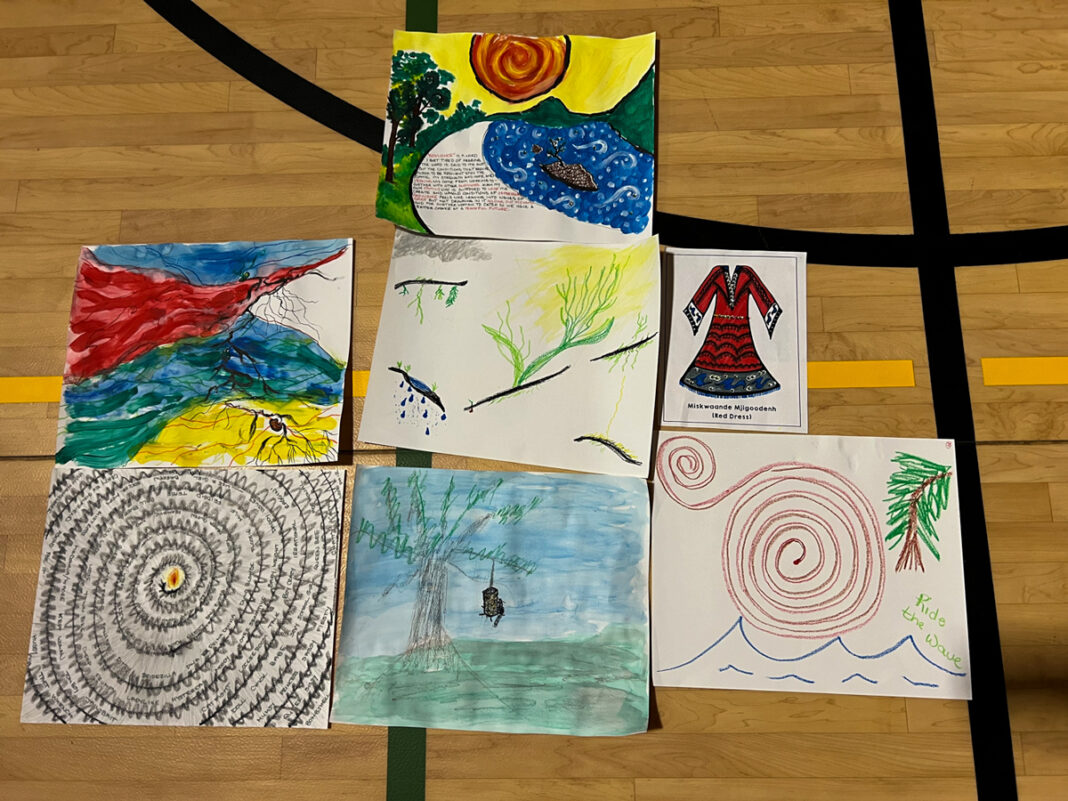

The commemoration featured a film screening of an NFB Film, a guided therapeutic art exercise led by Nicole Jol and a sharing circle. While the film depicted the history of feminism in Canada, attendees noted a lack of focus on Indigenous and other women of color, particularly on tragedies such as Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG2S). Furthermore, the absence of male presence at the event drew attention, despite men being primarily responsible for femicide cases—a point emphasized by the group, advocating for greater male involvement in preventing GBV incidents.

A concerning trend highlighted by a recent report showcases a rapid increase in femicides across Canada. The report detailed a distressing surge in violent deaths among women and girls between 2018 and 2022, with 850 deaths recorded in the past five years—equating to a woman or girl being killed every 48 hours. Moreover, between 2019 and 2022, there was a 27 percent rise in deaths involving male suspects. Although not all perpetrators were identified, 82 percent of known suspects were male, while 18 percent were female.

Focusing on the demographics of victims, the report estimated that one in five female victims killed by a male perpetrator were Indigenous, accounting for about 19 percent of cases. Shockingly, the fatalities left 868 children without mothers. Advocates have been fervently urging for the recognition of femicides within Canada’s Criminal Code or through dedicated legislation to afford legal protection to women and girls, especially those from Indigenous, Black and other racialized communities.

The report further revealed that from January to November 2023, there were 169 cases of femicide nationwide. Notably, according to The Ontario Association of Interval and Transition Houses (OAITH), Ontario witnessed 65 cases of femicide from November 26, 2022, to November 25, 2023—10 more cases than the previous year, despite a decrease in national numbers.

While the Canadian Femicide Observatory for Justice and Accountability (CFOJA) was established relatively recently in 2017, the term ‘femicide’ has a deep-rooted history in the country, dating back over three decades. Initially propelled by the mass femicide in Montreal in 1989 and groundbreaking research on femicide in Ontario that same year, the term has persisted. Notably, it intersects with the ongoing grassroots Indigenous movement, spanning three decades, shedding light on the disproportionate number of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG) in Canada.

The situation, as articulated in the 2019 MMIWG report as ‘genocide,’ remains intertwined with the term ‘femicide,’ underscoring the intersection of racism and sexism—both institutional and individual—that underpins this form of violence against specific groups of women and girls.