Enbridge anticipated to defy order

MICHIGAN—While it remains “highly unlikely” the controversial section of the dual Line 5 pipeline that runs along the lakebed through the Straits of Mackinac to Sarnia will actually be shut down by Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer’s May 12 line in the sand, a veritable hurricane of alarm has arisen with building steam as the deadline to shut down the pipeline nears.

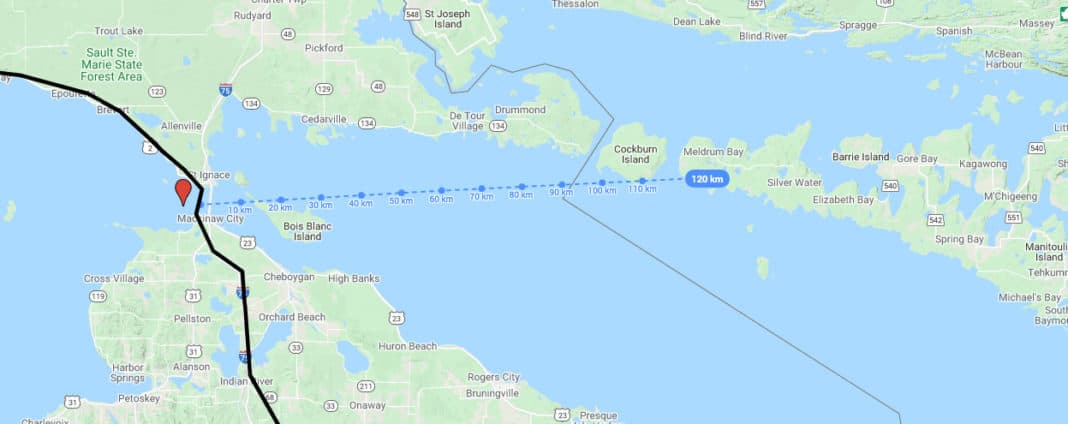

Shutting down the Line 5 pipeline through the Straits of Mackinac was a key plank in Governor Whitmer’s (an important supporter of President Joe Biden) election campaign. The pipeline transports western oil and gas from Canadian fields, beginning in Wisconsin and terminating in Sarnia, and runs along an easement provided by Michigan.

Enbridge has so far said it will refuse to comply with the governor’s order, citing its belief that jurisdiction over Line 5 lies with the federal government. But if Line 5 were to shut down for more than a few weeks, it could cause a massive disruption, according to Warren Mabee, director of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Policy at Queen’s University. “It would be chaotic.”

Complicating the environmental risk associated with the pipeline, which environmentalists score as high despite the lack of any spill from the underwater segment in its nearly 70-year history, is the long-term environmental damage caused by the fossil fuel industry in general—a key motivating factor for opponents of the line. Although environmentalists cite several Enbridge spills over the years, those spills came from sections of the pipeline that feature welded seams; Line 5’s underwater segment is of seamless construction.

Nonetheless, energy experts generally agree there needs to be a planned transition from fossil fuel dependence in the economy. The question is a balance between the immediate economic impact of a sudden shutdown and the potential for what would be a devastating impact in “the worst place in the world for a spill.”

But even the environmental issues are a mixed bag, at least in the short term.

“Line 5 is probably one of the most critical pieces of infrastructure for energy use in Central Canada,” said Aaron Henry, senior director of natural resources and sustainable growth at the Canadian Chamber of Commerce. “Shipping won’t work in the winter,” Mr. Henry points out, as that is “when portions of the St. Lawrence Seaway are frozen. It might be difficult to find capacity on Canada’s already busy rail lines. Trucks release carbon emissions and cost significantly more. It is a tremendous amount of product that suddenly no longer has a very safe, very efficient and very cost-effective method of transporting it.”

“There’s no natural replacement, there’s no other pipe that’s empty right now that they could just divert the oil through,” agrees Mr. Mabee, who notes that companies have been stockpiling to overcome a short-term loss of Line 5, but adds that those companies will be seeking to develop alternatives over the long-term. “So you’d be looking at some combination of ship, rail and truck. That’s just going to push your costs up.”

It will also up the ante on risk, as replacing Line 5 in its entirety through the straits would entail literally hundreds of thousands of rail cars travelling through countless small and large communities across North America.

But the impending increase in costs associated would prove an ally to environmental activists’ goal of reducing both nations’ reliance on fossil fuels, and by extension the battle against global warming.

Concerns of a spill in the Straits of Mackinac would be rendered largely moot by a proposed tunnel that would run far beneath the lakebed and is slated for completion by 2024 (although the permitting process may well be delayed or derailed by a decision to weigh the impact of the fossil fuel industry on the environment, as announced by the state’s agency overseeing the remaining permits).

The Anishinabek Nation has come out squarely on the side of shutting down the pipeline, saying its leadership “is disappointed with the federal government’s opposition to the closure of Line 5 in Michigan,” noting that this ignores the long-standing cross-border commitment to protect the Great Lakes via the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement.

They join American tribes in the Michigan region who are calling for Line 5 to be shut down.

“It is upsetting to see that the Government of Canada will pick and choose which treaties to uphold based on convenience and profit, rather than in good faith for the health, safety and well-being of all inhabitants of these lands,” said Anishinabek Nation Grand Council Chief Glen Hare in a release announcing the UOI support. “The Government of Canada is not upholding the treaties made with the First Nations but will uphold the 1977 treaty for pipelines.”

The release notes that the five Great Lakes together comprise the largest body of freshwater in the world, making up more than 20 percent of the world’s freshwater supply and stretching 750 miles from east to west, bringing drinking water to approximately 40 million people and providing a home to over 4,000 species of plants and wildlife.

The release goes on to cite that in August 2020, four tribes comprising the Bay Mills Indian Community, Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians and Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi had been granted the right to participate in Enbridge’s Line 5 permitting process.

The release points out that the Straits of Mackinac lies within the Bay Mills Indian community’s homelands where they have treaty rights to hunt, fish and gather. “Bay Mills is opposing the existing Line 5 pipeline and the tunnel construction project and is being represented by the Native American Rights Fund (NARF) and Earthjustice in the intervener status and legal proceedings,” points out the release.

Bay Mills’ concerns include impact to treaty rights to hunt, fish and gather; impacts to the environment: ecosystems, fish and wildlife; and missing women and children (through an alleged correlation between Enbridge contractors and the missing).

“As First Nations people, we have direct responsibility to protect water and a deep spiritual connection with water. Should anything that’s being transported in these 67-year-old pipelines get into the Great Lakes, it would have devastating effects and irreparable consequences,” said Grand Council Chief Hare. “We stand in solidarity with our relatives on the other side of the Medicine Line who are working relentlessly to protect our Great Lakes. Those in positions of power who can put an end to this environmental threat need to step up and help us in our efforts to protect our water sources.”

The release goes on to say that the lack of co-operation on this matter from the federal government “violates several United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), including but not limited to, Article 19: “States shall consult and co-operate in good faith with the Indigenous people concerned through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free, prior and informed consent before adopting and implementing legislative or administrative measures that may affect them; and Article 29: Indigenous peoples have the right to the conservation and protection of the environment and the productive capacity of their lands or territories and resources. States shall establish and implement assistance programmes for Indigenous peoples for such conservation and protection, without discrimination.”

Enbridge vows to continue operating the pipeline beyond the deadline set out by Governor Whitmer unless presented with a court order. Both the state and the company have entered into a court-ordered mediation process, but the next session in that process is slated for a week after the deadline to close down the pipeline.

In an interesting, yet quite possibly unconnected anecdotal observation, online searches for information on Line 5 and seeking news stories addressing the issue almost exclusively turned up news items citing concerns on both sides of the border on the economic impact and job losses that will stem from the shutdown—with environmental voices being largely absent except as cursory footnotes in those same news articles.

Among the more immediate environmental concerns, model projections of a potential spill in the Straits of Mackinac show a worst case scenario wherein Manitoulin’s south and west shores are inundated by a massive spill. On the economic side of the coin, many Island homes depend on fuel oil or propane supplied by Line 5.