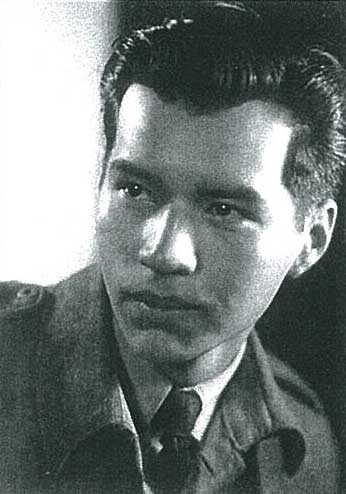

MESA, ARIZONA—Justin Roy, formerly of M’Chigeeng, took time out from his busy day to speak with The Expositor last week, reflecting on his time spent in service in WWII, specifically his survival of D-Day, the landing of Canadian troops in Normandy on Juno Beach, the Canadians’ assigned landing place.

MESA, ARIZONA—Justin Roy, formerly of M’Chigeeng, took time out from his busy day to speak with The Expositor last week, reflecting on his time spent in service in WWII, specifically his survival of D-Day, the landing of Canadian troops in Normandy on Juno Beach, the Canadians’ assigned landing place.

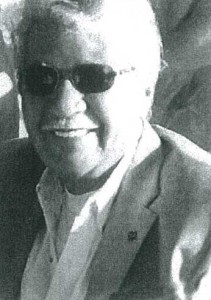

Mr. Roy, at age 89, still owns and operates a sheet metal business in Mesa, Arizona. Keeping busy, he says, is incredibly important so that the horrors of war don’t make a permanent home in his mind.

Mr. Roy grew up in M’Chigeeng, but left at age 13 to find his own way in the world after his father passed away, first working at a lumber camp in Whitefish Falls, then on to Sudbury. The boy eventually found himself in Sault Ste. Marie where he secured a job at the steel mill.

In 1943, at age 19, Mr. Roy travelled to Toronto to enlist with the Canadian Forces, explaining that like everyone else at that time, he spent some time at the CNE’s Horse Palace (where basic training was conducted in wartime) before being shipped off to Petawawa for four more weeks of basic training.

Wanting to join the paratroopers and the air force, but being denied due to a lack of education, Mr. Roy settled into his role in the 3rd division of the Allied Expeditionary Special Forces.

After landing in England, the young soldier and his unit spent more time in advanced training, and then it was time—Mr. Roy was called to the front. Only in his case, the front lines were to be the deadly beaches of Normandy; the horrific scene of battle known in history as D-Day.

Of the over 5,000 Canadian losses on the beaches of Normandy, none suffered more casualties than the 2nd and 3rd Canadian divisions, of which Mr. Roy was a part.

“I was part of the second wave,” the veteran explained. “We were told the day before (that they were to be deployed) and we knew that something big was going on.”

“When you got off that ship, down that rope ladder, your life expectancy was 15 minutes,” Mr. Roy continued. “The water was so rough, sometimes it was over our heads.”

He said their objective was a point of land seven miles inland, which he achieved that day. “There were 45 of us left out of 200,” he added.

“On about the second day I crawled under a tank that had been blown up and played dead for two days,” Mr. Roy shared.

When he felt it was finally ‘safe’ enough to crawl out and rejoin his division, the group of men spearheaded their campaign seven times.

“I never thought I’d get out of there alive,” he said. “Everyone was my age, 18 or 19, laying out there in the field. They were crying and yelling, but there was nothing you could do.”

“I was shot at, I got shrapnel in my back,” he said, noting that while it didn’t puncture his lung, it left a shadow that required surgery. “I had to have surgery in England. I was in the hospital for two months, then convalesced for another three months.”

“I wanted to go back to the front lines, to be with my buddies, but they wouldn’t let me,” Mr. Roy said. The soldier was then assigned to be a driver for senior officers until the war ended.

A young man from M’Chigeeng eager to see the world, Mr. Roy requested a one-year leave of absence from the army and spent the year visiting countries across Europe—England, France, Germany, Belgium, Holland, Scotland—finding work in restaurants, shipyards, and hospitals to see him through. In 1946, Mr. Roy reported back to the Canadian embassy in London and asked to be sent home.

Sailing aboard the Queen Mary, Mr. Roy arrived in New York City then hopped a train to Toronto, then on to Sault Ste. Marie, hoping to get his old job back, but they no longer had a position for him. It was also here, fresh from Europe, that he felt the sting of racism. Mr. Roy said he went out and purchased some new civilian clothes, some Levis and shirts, to meet his old friends for a drink in a local bar. The bar keeper wouldn’t serve him, however, as he was an Indian. “I just broke down,” he said.

He tried his hand at farming in M’Chigeeng for awhile, but blames Indian Affairs for its total control over everything for this venture failing. Mr. Roy then worked at Falconbridge in Sudbury for seven years, again experiencing racism. He said he was the first First Nations man in his particular mine, and he was forced to do the dirtiest jobs, “but I didn’t mind, I got a paycheque,” he said.

Mr. Roy and his late wife Joyce, also of M’Chigeeng, eventually moved to the United States, where he worked more mining jobs before going to school to become an air conditioner repairperson and sheet metal contractor.

Mr. Roy and his late wife Joyce, also of M’Chigeeng, eventually moved to the United States, where he worked more mining jobs before going to school to become an air conditioner repairperson and sheet metal contractor.

He explained that when he started off in Arizona, he had perfect credit and a small savings account, however the bank was leery of giving him a bank loan because of his race. Mr. Roy and his wife spent the first little while living out of their car, until they could get on their feet. Mr. Roy has been living there for almost 50 years.

“I had a pretty good life once I started contracting,” he added.

“I kept the shop to give me something to do,” he explained. “I’m 89 now and I still enjoy the work. I can’t sit in that rocking chair.”

Mr. Roy is a member of the local chapter of the VFW (Veterans of Foreign Wars) and says he attends Veterans Day (Remembrance Day) services in Mesa.

As a result of his time in war, Mr. Roy suffers from post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). “Sometimes your nerves just get the better of you,” he said. He admits to having barbed wire all around his shop, a result of the PTSD.

It was while receiving counselling for his PTSD that Mr. Roy met his second wife, Barb. They have been married for 10 years and he credits her helping him deal with his stresses immensely.

All of Mr. Roy’s siblings in M’Chigeeng have since passed away, but he and his wife try to make it to Manitoulin at least once a year and look forward to visiting his nephew Wally Corbiere and wife Menesa.

“I think the Island is one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever been,” Mr. Roy shared. “People that live there don’t realize it.”