MANITOULIN—Health Canada has released its long-awaited update to Canada’s Food Guide to acclaim from public health organizations and nutritionists, but the response from food-producing industries on Manitoulin has been considerably more varied.

The food guide’s 2019 update has been several years in the making. Health Canada has reviewed food science and statistics since 2013 to determine areas that they had wished to address.

The government webpage that outlines its food guide revision process states that food and beverage industry representatives had not been consulted during the policy development phase. However, they were still welcome to comment during the online public consultation phase of the project.

Industry efforts were still working hard behind the scenes. In August 2017, Canada Beef—an advocacy group for beef farmers across Canada—published a post on its website that informed beef farmers that the online consultation process was open.

But rather than registering as someone who uses healthy eating recommendations “to help others through my work or an organization I am with,” the post tells beef producers to register “for myself, my family and others I care about,” the other option available.

“It would likely be most powerful to enter your objections as a concerned citizen rather than a farmer or rancher, so that it is seen unbiased (sic),” the post states.

Jordan Miller, director-at-large with the Beef Farmers of Ontario (BFO), says his organization has mixed feelings about the way the government has released the document and the contents within.

“The overall movement away from livestock and agriculture to plant-based proteins raises some concerns. I believe it’s short sighted in terms of the health and environmental impact,” Mr. Miller says, adding a claim that the research the government has relied upon for the final document has not held up in objective evaluations. The Expositor has not investigated this assertion.

Preliminary reports about the new food guide had seemed much harsher towards meat and dairy producers.

“The initial communication down the pipeline was it would be explicitly encouraging Canadian citizens to eat plant-based proteins. We thought it would have had devastating health and environmental impacts for the government to make a statement like that,” says Mr. Miller.

“BFO had some lobbying done for the government to go back and reconsider some of the statements being made. Overall, we haven’t had a huge voice in terms of how things were done,” he continues, and adds that their efforts performed “unsuccessfully” in several ways.

However, he says there are certainly positive aspects to the food guide that BFO supports, including that in the final version, lean beef is included as a food suggestion.

“BFO is very encouraged by the messaging of eating as a family, holistic consumption and how what you eat affects your day-to-day-life and your community. We thought it was positive that the encouragement of lean beef as a protein was included,” says Mr. Miller. “We also like the idea of having more family meals. That’s a huge aspect that’s missing from our culture in the way we conduct our families.”

In addition to the guidelines about what kinds of foods to eat, the food guide also includes recommendations of how to eat better, such as cooking more often, being mindful while eating and sharing meals with others.

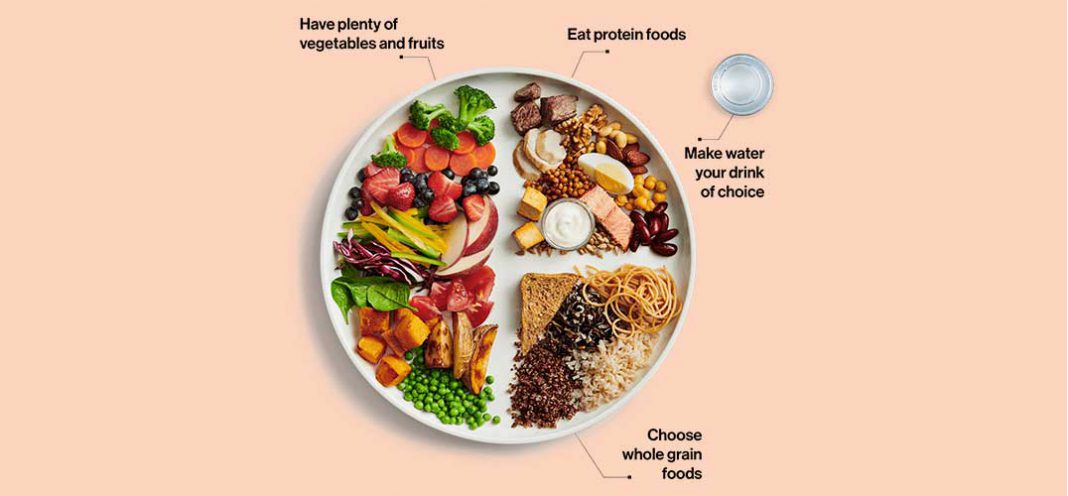

In the graphical representation of the new food guide, fruits and vegetables take up half the plate, with another quarter being assumed by whole grains and the last quarter made up of proteins, including lower-fat dairy products, protein-rich plants and meats.

The graphic containing the controversial protein category only features a few small cubes and slices of meat, a miniscule bowl of yogurt and a quarter of a boiled egg. The rest of the items in that section are plant-based, such as beans, lentils and nuts, and two small squares of tofu.

The few options in the diagram have drawn criticism from advocates who say they do not include Indigenous foods or account for the higher prices of good-quality fruits and vegetables. However, Noojmowin Teg Health Centre Registered Dietitian Joby Quiambao says there are alternatives available to include healthy foods like vegetables within most budgets.

“Canned goods and frozen vegetables and fruits can be budget-friendly and economical, while being just as nutritious. Chickpeas, beans and legumes are widely available in frozen food sections. Seeing those items on the plate [graphic] will give more encouragement,” she says.

In regards to the concerns about Indigenous foods, Ms. Quiambao says specialized guidelines should be coming soon that address food needs for different cultural and age groups.

“In the past, there was a time gap between the national guide and an adaptive version that accounts for more traditional foods, diversity and environmental sustainability. They will be working with Indigenous policy makers and gathering more feedback from communities on how to be more present,” she says.

A lot of organizations rely on the food guide to inform key aspects of their work, including hospitals and long-term care facilities whose missions include providing healthy food for their patients. Ms. Quiambao says that because the recently-released guidelines offer information in a broad, generalized sense, people may see the guide as daunting.

“I encourage people to see a dietician in a healthcare centre for further guidance of how it can be applied to them, including any financial constraints they may have,” she says.

Canada has a separate food guide for First Nations, Métis and Inuit audiences but it has yet to be updated alongside the main Canada’s Food Guide. The latest version of that guide had been published in 2007 and still includes both a meat and alternatives and a dairy and alternatives category.

Ms. Quiambao stresses that this new release is only the first phase of Canada’s new food guide and that supplements such as the Indigenous guidelines are in development.

“This is an exciting time,” says Ms. Quiambao, “but there will be more coming later this year.”

On farms across Manitoulin, cattle and dairy producers are dealing with the new realities of Canada’s updated food recommendations.

“Dairy producers as a whole are a bit upset that there’s much less focus on meat and dairy products. We feel that there’s certainly still evidence—and mounting evidence—to show that dairy products are still part of a healthy, balanced diet, and that isn’t really reflected in the new food guide. It’s sort of been brushed to the side,” says dairy farmer Alex Anstice who helps run a four-generation family farm called Oshadenah Holsteins in Tehkummah.

Mr. Anstice says reducing meat and dairy consumption is not the most important objective that the food guide could be advocating for.

“There should be more emphasis put on supporting local agriculture in your area and local food, no matter what kind it is. They really missed on that. Dairy and beef are about as local as you can get [on Manitoulin]; our milk is only shipped an hour north of the Island and consumers should take that into consideration when they’re buying for their families,” says Mr. Anstice.

“The agriculture sector is a large part of the economy and they need to consider that these farm families should be supported, too.”

He says he is not entirely sure what the new guidelines will mean for his livelihood and the lives of his fellow farmers, but says he questions how much weight people put on Canada’s Food Guide when choosing foods for their families.

“I feel like people are still going to buy dairy and I hope they would still support local farmers,” he says. “Dairy is very important for the development of children, especially for six of the eight essential nutrients that Canadians often seem to be deficient in. This is easy-access and nutrient dense and is definitely part of a healthy, balanced diet. Everything in moderation.”

Mr. Anstice also questions the scientific merit for avoiding meats and dairy.

“Whatever the reasons are for people to be moving away from a meat- and animal-sourced diet is probably not founded on sound science, and we hope in the end that science is what people listen to,” he says. “The dairy products mentioned [in the guide] are the low-fat variety which goes against recent research that those fats are good for us. Often with low-fat dairy products, they put more sugar in because they don’t taste as good, which isn’t a good thing, either.”

Part of the distaste for dairy and meat products, Mr. Anstice believes, comes from misconceptions about animal treatment and quality standards. He says animal welfare standards are very high in Canada and are monitored closely, alongside product testing in areas such as bacteria content.

“They’ll come in and assess the animals’ welfare and if something is wrong, then it’s certainly time to make changes. It’s part of a pro-action plan. And these cows are our livelihood and really part of the family since we’re seeing them several times a day. Dairy farmers are very concerned about caring for their animals and producing quality products for customers to buy,” Mr. Anstice says.

Beyond the producers, retailers will also be feeling the impacts of the new food guide to varying degrees. For TJ McDermid, who runs Manitoulin Meat Boss just outside Providence Bay, the updated Canada’s Food Guide is a welcome new document.

“There are some good recommendations with it, such as cooking more often, planning meals, stuff like that. We can help customers with that and we have box programs so they always have frozen and fresh foods available. Plant-based proteins are an excellent and healthy alternative,” he says.

While praise for a document that advocates for less meat and dairy consumption may seem odd coming from a butcher, Mr. McDermid says he does not expect his business to be widely impacted by the new food guide.

“We always cut our meats how our customers want it. If they want to trim extra fat off to make it leaner, that’s always available,” he says. “We’re not changing anything, just focusing on providing our customers with a quality product.”

He adds that having a reference document like this is useful to inform consumers and producers who may find answers to important questions through the guide.

“With a small shop like ours, we are able to offer alternate products to people wanting to follow the food guide. If anyone has questions, this is a good thing we can point our customers to,” Mr. McDermid says.

Ultimately, Canada’s Food Guide is just that—a guide. Although it has been compiled with the aim of using up-to-date research to help make Canadians healthier, how closely one chooses to follow the guide or not is entirely a personal choice. Regardless of whether an individual is for or against the updated document, the new Canada’s Food Guide is bound to impact the way Canadians as a whole conceive of their food.