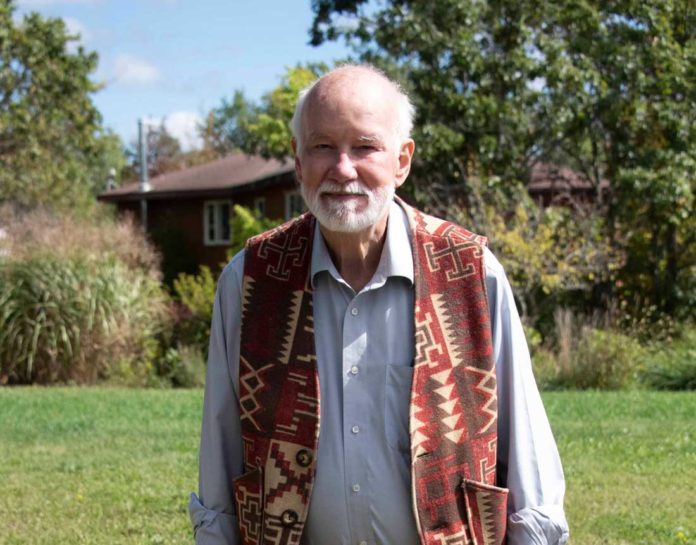

MONTREAL—Between December 7 and December 19, leaders from 195 countries came together at COP15 in Montreal, Quebec to negotiate an agreement for the future protection and conservation of the world’s biodiversity. Manitoulin Island resident Kim Neale was there as a panelist and observer, and shared her experience with The Expositor.

“I did make it here but just barely!” she said. “It was all very serendipitous. The work that I have been doing in wholistic nature valuation to measure nature’s contribution to people and livelihoods has somehow seemed to capture hearts and minds.”

Ms. Neale has been volunteering her time with the Conservation Through Reconciliation Partnership (CTRP). The research group was recommended as one of the direct actions from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Calls to Action; it was also suggested in ‘We Rise Together,’ the 2018 Indigenous Circle of Experts Report on Indigenous-led Conservation. “One of the questions was how do we accelerate Indigenous Conserved and Protected Areas (ICPAs) as part of these calls to action,” Ms. Neale explained.

The CTRP is looking at all of the different ways ICPAs can be enabled. The research partnership is led by Indigenous nations in partnership with two non-Indigenous primary faculty members from the University of Guelph and focuses on seven streams of research, including bio-cultural indicators, ethical spaces, and two-eye seeing (combining the Indigenous way of knowing with Western science). The seventh stream: infrastructure, finance and economics, is where Ms. Neale fits in.

Ms. Neale has been doing this kind of finance work, involving carbon credits and nature valuation, at the not-for-profit Municipal Natural Asset Initiative (MNAI), bringing forward “more wholistic nature valuation models that go beyond carbon.”

The MNAI is currently undertaking a full natural asset inventory for all of Treaty One territory in collaboration with the Winnipeg metropolitan region, which includes 18 municipalities within Treat One Territory. “It’s the first natural asset inventory that’s being done where the municipal and watershed colonial governance is also at the table with the Indigenous nations that hold land rights,” said Ms. Neale. “How do we make all of our development decisions moving forward in a good way that doesn’t speed up biodiversity loss and that does protect us from the impacts of climate change?”

It’s not easy because they’re “smashing together” two very different value systems, to come up with a nature valuation that reflects what the community thinks. “When you include Indigenous voices and leadership at the table you get a very different nature valuation,” she said. “I believe you get one that is more appropriate for the marketplace.”

That’s mostly what she talked about at COP15, “the importance of integrating Indigenous knowledge and Indigenous approaches to nature and using bio-cultural indicators in all nature valuations, because when we just value nature as carbon, we’re undervaluing nature.”

“When you centre Indigenous knowledge, leadership and bio-cultural indicators in valuation models, you begin to see what could be a more just marketplace,” Ms. Neale said. She hopes that every IPCA in Canada (there have been more than 100 IPCAs declared) “doesn’t just sell a carbon credit but sells some kind of social impact bond as well to funnel capital into the conservation that we need to meet the 30 percent by 2030 goals.”

Right now, she said, Canada has enough IPCAs declared and First Nations willing to implement IPCAs to meet those goals, but “Canada simply hasn’t acknowledged or provided the funding required to be sure those IPCAs can be long-term sustainably conserved areas protected from development.”

The concept of nature valuations was somewhat novel at the conference, she noted. “Everybody is so obsessed with carbon. Some of these other social financing mechanisms are actually made for investors who want to invest in social good. A lot of the social impact bonds that can be used for nature and these IPCAs can actually still give investors a return on investment. It might not be as high as their oil funds but there’s other social benefits that they get. I’m really just trying to be on the cutting edge of that research to make sure that Indigenous rights and United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples are not missed in that value. If we can do that right, we could get a good market price for nature and we could shift the market generally away from resource extraction and into resource protection.”

“I’ve obviously been very focused on the Indigenous-led piece and what’s going on in the global south and learning about some of the models in Kenya and Southeast Asia on conservation finance with Indigenous peoples. It has been absolutely fascinating,” she said. “Several banks, pension funds and other Indigenous representatives from the global south reached out afterwards.” She will be meeting with them in January to work on next steps.

Whenever she wasn’t speaking, she spent time learning from other presenters and attendees in the convention centre, especially in the first ever COP Indigenous village. “Just to be in that room with so many ministers, including Environment and Climate Change Minister Steven Guilbeault was amazing,” she said.

“For the next COP, I think we need a Manitoulin crew,” Ms. Neale said. “There are so many people here doing such great community work on the ground. These ‘pie in the sky’ policy folks need a bit of realism in the building.”