EDITOR’S NOTE: In the first edition of The Manitoulin Expositor for 2017, Shelley Pearen provided Expositor readers with a glimpse of Manitoulin in 1867. She summarized Manitoulin’s history and described a typical New Years. On January 18, 2017, she described the resettlement of the Anishinaabeg occurring in 1867. Today she shares 19th century descriptions of Little Current.

by Shelley Pearen

Little Current, called Wewebijiwang by its Anishinaabeg residents, Petit Courant by French traders, and Shaftesbury by the post office, was an active Anishinaabe settlement in the early 19th century. The Hudson Bay Company’s La Cloche post records, which survive from 1827, indicate that their traders regularly visited Petit Courant for maple sugar, fish and skins.

La Cloche post traders also visited Sheshegwaning, Point aux Erables (Maple Point) and Sheguiandah but it was Little Current’s unique location that made it desirable not only for Anishinaabe entrepreneurs, but also traders, government officials and settlers in the mid-19th century.

By the 1850s, Anishinaabe families at Little Current sold wood and supplies to the steamboats travelling east and west. The Obetossaway (or Ahbedosswey) family were well-known for selling fuel wood and providing short term accommodation to travellers.

An 1860 census for “Wyabegwong,” population 52, included the Eshkewahbic, Ahbetosowai, Eshkemah, Mocataibin, Cahcahkewai, Shokan, Manitahben, Sahquaibeness, Bob Mocataibin and George Obbetosoway families. They grew corn, potatoes, oats, peas, beans, and squash; raised horses, milk cows, oxen, pigs, and fowls; owned 130 fish barrels and 4 mackinaw boats; and produced a large quantity of maple syrup. Clearly it was a vibrant fishing and trading community.

Though three Little Current residents were persuaded to sign the 1862 treaty, they were clearly not told that the treaty meant that they and their neighbours would be relocated. The Manitoulin Treaty of 1862 stipulated that Anishinaabe residents could not select or remain on potential harbours, town sites or mill sites. Little Current included all three prohibitions.

An 1864 census of Little Current by Rev. Jabez Sims listed the George Ahbedosswey, Henry Eshkemah, James Columbus, Manitwahssen, Ohbwinwawaajewunookwa, James Sac, Oogemah, John Mukkudabin, Robt. Black, Minegwud, Kitty Ahbedosswey, Wm. McGraw, Charles (Cooper) Kahgahgeway, Cooper’s son in law, Peter Metahbe, and Shewetabgun families. Sims estimated the population at 79 or 16 families.

That same year, surveyor Alexander Niven reported that nine families or 52 people, lived at Little Current who “subsist chiefly by fishing, growing Indian corn and potatoes, and making maple sugar.” Niven was clearly focused on surveying lots and not on counting residents.

In 1865 Sims listed: G Ahbedosswey, McGraw, Columbus, Oogemah, Mukkuhdabin, Kahgahgeway, Minegwud, Metahbe, Ishkemah, Sacquabunesse, Manitowaussen, and Kitty Ahbedossway as Anishinaabe residents of Little Current, all members of the Anglican mission. He also noted that four non-Native families were living there.

In October1865 Charles Dupont, the Indian Department’s agent responsible for resettling Anishinaabe according to the terms of the treaty, reported that there were eight Anishinaabe families living at Little Current who wanted to settle immediately in the rear of the village.

On December 31, 1866 Rev. Sims reported that a few poor settlers who had located on some government land, in or near Little Current, that a store or two were in existence in the village, and “that worst of all adjuncts —a tavern.” Six months later, in mid-1867, he noted that 15 settlers had come to the Island.

In March 1867, Superintendent Dupont described Shaftesbury as containing Thomas Dodd’s store and wharf, James Phipps agent and wharf, John McClarty’s house and proposed wharf, David Moor Smiley’s large wharf and building under construction.

Rev. Sims, who had settled at Manitowaning in 1864, witnessed the transition of Little Current from an entrepreneurial Indian settlement to a non-Native settlement. In 1867 its original Anishinaabe fishermen and wood suppliers were being relocated to the new Sucker Creek Reserve. Non-Native traders quickly took over the lucrative steamboat trade. Sims expressed his concern: “The settlement of the Island by the whites has operated very much against the interests of the Indians.”

An 1868 census of the Little Current Anishinaabeg, recently relocated to Sucker Creek, listed the Ooshkewahbik (2nd chief), Wahsahgezhik (2nd chief), Shewetahgun, Medahbe, M’grahShoken, Mukuhdaben, Kahgahgeway, Sacquabuness, Eshkemah, Cath. Qwewis, and James Barr families, population 62.

Sims made a list of non-Native settlers in 1868, with their date of settlement. For Little Current he listed the following families: G.B. Abrey 1868, John Burkitt 1862 (left), E. Johnston 1866 (left), J. McClarty 1866 (left), D. Mckenzie 1865, D.M. Smiley 1866, J. Burnett 1866, Taylor 1866 (left), Dodds 1865, Miller 1868, Brodie 1866 (drowned), Bryan Mackey 1866, Abraham Johnson 1868, Wm. Sullivan 1865, and George Burkitt.

Sims’ list for Howland Township included: Abraham White 1868, John Atkinson 1866, S. McLean 1866, Wm. Dempsey 1866, H.C. Fraser 1864, Humphrey May 1860, Griffiths 1868, David Lewis 1866, Nelder 1868, Nicholson 1868, Oliver 1867, John Douglas 1867, Ferguson 1867 (left), and Boday 1865. In addition, he listed John Dunlop 1866 in Bidwell, Philip May 1830 at Wallace Mine, R. McKenzie 1866 La Cloche, 20 English at the mill at Michael’s Bay 1867, and the Indian Department’s surgeon T. Simpson, superintendent Wm. Plummer and clerk McGregor Ironside at Manitowaning.

Ontario Land Surveyor T.J. Patten, who described himself as a resident of Little Current since 1867, wrote an article entitled “The Early Beginnings of Little Current” that was printed in the magazine Mer Douce in June 1923. The following extract is from Mr. Patten’s account.

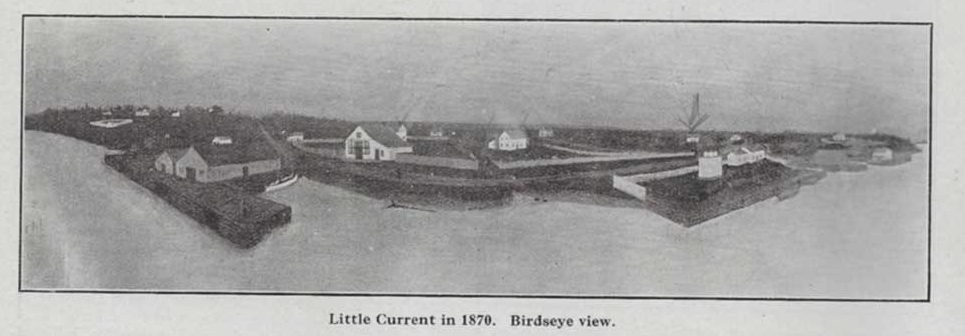

“In 1865 my brother-in-law, George B. Abrey, Dominion Land Surveyor, came to the Manitoulin to survey townships for the Indian Department. He came in a small schooner with his party from Hamilton, and the passage occupied about six weeks. My sister, Mrs. Abrey, and her two little girls, one is Mrs. Stuart Jenkins of McGregor Bay, followed the next year and wintered at Little Current in the small log house which is shown in the corner of the stockade on the side of the hill, to the left, in the picture. Shortly after they bought the dwelling which had been built by the Hudson’s Bay Company, and lived in it until they removed to Toronto in 1882. Mr. C.L.D. Sims a few years ago bought the property and remodelled the dwelling. A portion of the old dwelling is shown behind the large store in the centre of the picture.

“The writer came to Little Current in 1870 to live with the Abreys. At that time there were only about five or six white families in the village, and a few Indians. Humphrey May, the first white child born on the Manitoulin and still living here, hale and hearty, had been settled here a few years, also William McKenzie, whose father, Donald McKenzie, was lightkeeper for many years. George P. Burkitt, Donald McKenzie’s son-in-law, had kept a store. He was later Captain of the Waubano, on which he was lost, with all hands, in November, 1879. Capt. Burkitt’s father, was some years previous to 1870 in charge of the Anglican Church Mission here. The late Rev. J. W. Sims had been in charge of the Anglican Mission of Sheguiandah.”

William Griffiths, Mrs. William McKenzie’s father, kept a hotel. Bryan Mackie, Mrs. Brydon’s father, also kept a hotel, and David Miller, J.P., kept a general store, and had a shop license to sell liquor. Mr. Abrey had completed the surveys allotted to him, and had bought a general store which included a shop license. The late Warren R. Abrey, Registrar, was subsequently a partner, and were known as Abrey Bros. Quite a contrast to present conditions under the Canada Temperance Act which has been in force on the Manitoulin since 1913.

There were a few settlers in the adjoining townships. The land had only recently been in the market for sale. The surrounding country was mostly dreary and uninviting owing to the terrible fires which swept over the Island.

As in all new settlements law and order was disregarded somewhat. As an instance, the first school section on the Island had just been organized, and a Mr. Tom Reid was engaged to teach. Tom was a character, of the good-hearted, jovial rollicking type, and had served in the Confederate army. Like a certain writer’s definition of a boarding house landlady, he was equal to anything. He boarded at the Mackie hostelry. In addition to his hotel business, Mackie, who was also a school trustee, had built a small saloon on the steamboat dock, thinking of course to better serve the travelling public and enhance his income as well. When the steamboat whistle blew, Tom would immediately dismiss school and go down to the wharf and tend bar, and sometimes did not return to school that day. Of course, those conditions did not endure long. The saloon building was moved to the south side of Campbell Street, near Mrs. Maltas’ dwelling, where it stood until recently, and was known to old timers as the “Bummer’s Roost.”

During church service also, when the steamboat whistle blew, it was customary for the congregation to rush down to the wharf without waiting for any benediction.

The first colonization road on the Island, from Little Current to Manitowaning, had been recently built. It is now known as the old road. The new, or lower road, is the one which is nearer to the lake shore and goes through the Ten Mile Point settlement.

In winter the mails came from Penetanguishene, and later from Parry Sound, also from the Sault, and were exchanged here. In spring and fall it was not unusual for them to be as much as two or three weeks overdue, particularly the one from Penetanguishene. One from there never came. One courier and the dogs and mail drifted on the loose ice into Georgian Bay and were never seen again.

Shelley Pearen has been researching Manitoulin history for 40 years. Her ancestors included Rev. Sims and D. McKenzie. She is the author of the popular books ‘Four Voices The Great Manitoulin Island Treaty of 1862’ and ‘Exploring Manitoulin.’ Shelley is currently transcribing and translating the Jesuit’s Wikwemikong Diarium 1844-1873.