Young woman’s first transplant is failing

LITTLE CURRENT—Seven years ago, Kinga Casson of Little Current caught something of a Hail Mary pass when her mother Anne proved to be a match for a desperately needed kidney donation. Three years later, that kidney also started to wane, and Ms. Casson was again put on the list for a donor in both Ontario and nationally where she has languished for four years.

Ms. Casson has been dealing with chronic kidney issues since she was 16, but it was after she turned 20, following a high-risk pregnancy, that her condition spiraled dramatically.

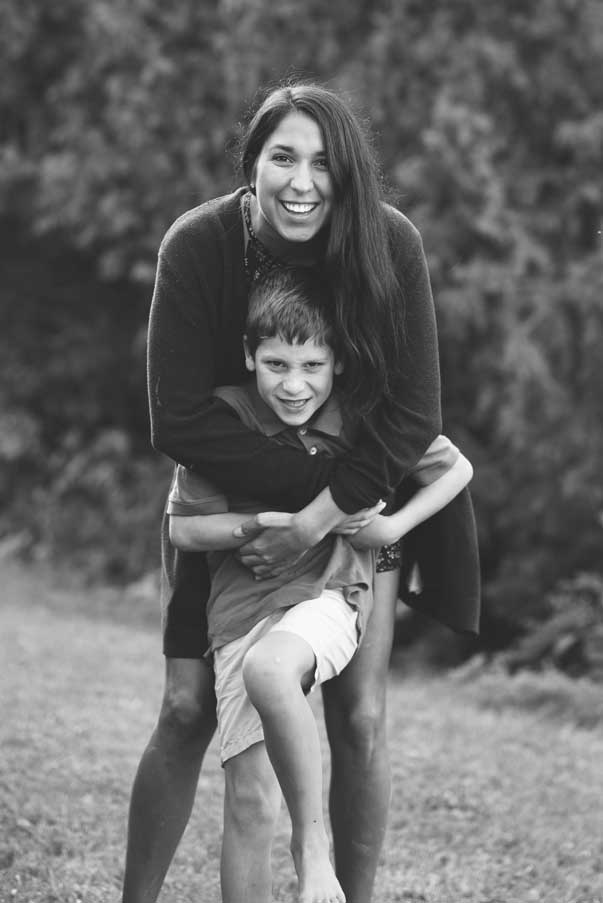

“My beautiful son Jack was born premature when I was 20 years old,” she recalled. “He was just three pounds, six ounces.”

Mother and child spent a month in a natal critical care unit in Toronto. Six weeks later Ms. Casson began exhibiting signs of kidney failure and she was placed on the list for kidney dialysis at Manitoulin Health Centre.

“While I waited for a spot to open in Little Current and cared for my newborn child my mother drove me back and forth to Sudbury twice a week for treatment.” Once a spot opened in Little Current, the young mother would spend three hours a day, twice a week, hooked to a machine that cleared her body of lethal toxins. “During this time, we investigated every option for a kidney transplant through the Toronto General Hospital, which has one of the best transplant programs in the world. Eventually, we learned that my adopted mother was, however unlikely, a match.”

Ms. Casson received a kidney from her mother on March 4, 2014, but her ordeals were far from over. “After some complications, including needing three blood transfusions, and 10 days in the hospital, I spent two months in Toronto seeing doctors, tests, levelling medications and just being monitored closely,” she recalled. “Eventually, after the two months in Toronto, I was able to head home to Manitoulin and start my life.”

Ms. Casson set about charting the course for her life, going back to college to study business administration, graduating with honours, settled into a good job and was even able to do a bit of travelling when things were stable. “I did a two-week trip with my sister through Rome, Venice, Florence and Budapest,” she said. “It was an incredible trip I’ll never forget. I was able to live my life again and be the best mom I could be.”

But in October 2018 Ms. Casson began to feel ill. “I got sick and quickly realized I was in kidney failure again,” she said. “Less than a week later I was admitted to Health Sciences North in Sudbury until I was able to get my urgent central line catheter placed.”

The catheter in place, the hospital performed a short dialysis run. “While dialysis is a treatment, it is not a cure,” said Ms. Casson. “Dialysis comes with very serious risks and complications. Some of the main risks and complications are sepsis/infection, bone disease, anemia, blood pressure issues (both high and low), cardiac issues and more.” The process and kidney failure itself places huge strains on the heart.

“It’s been just over four years since I started dialysis for the second time,” said Ms. Casson. “This time around I am doing dialysis three days a week and each run is four hours. I’m very fortunate to live very close to the unit on Manitoulin Island but being hooked to a machine for 12 hours a week is just not a healthy or great way to live, and I see how hard all of this is on my son.”

“This is Jack’s normal,” explains Ms. Casson. “He doesn’t know anything different because I’ve always been sick.” But as her son grows older and gains greater understanding of his mother’s condition her condition is taking a toll on him as well. “It breaks my heart all over again,” she said. “He fears death so much and worries often. He knows he is my world and the reason I fight as I do.”

Those concerns are not at all irrational, although 2022 started out on a stable note, things took a turn for the worse in early February.

“My potassium levels spiked to levels that should have given me a heart attack,” she said. “This was the tipping point that sent me into months of tests, treatments, procedures, late night ambulance rides and emergency room visits.” Just a couple of her many symptoms were muscle weakness and paralysis.

“In early March I had a parathyroidectomy due to the high levels being caused from dialysis,” she said. A parathyroidectomy involves removal of parts of her thyroid gland. “After all of this and a bout with COVID that meant I was isolated in Sudbury for 10 days—we hoped we could get back to our version of a somewhat normal life.”

But three weeks later those hopes were dashed as her health once again began to deteriorate. Ms. Casson began experiencing seizures and periods of being unresponsive. She is working with a neurologist to discover the source of these latest symptoms. Her health appeared to stabilize, and she once again set about “normalizing” her life as best she could.

“This summer I was able to have a couple of months where I was doing well,” she said. “I was enjoying summer, working out a lot and enjoying time with my son.”

But by the end of August her health once more took a turn for the worse.

“I started to get a lot of swelling in my face, pressure on the right side of my face and ear and developed superior vena cava stenosis,” she said. “This means that the central line they had used for my dialysis, my lifeline, had caused my SVC (the superior vena cava, a major vein in her upper body that carries blood from the head, neck, upper chest and arms to the heart) to reduce its ability to move blood through to my heart.”

Then came an angioplasty, a procedure to open narrowed or blocked blood vessels that supply blood to the heart. Hope was soon to be dashed, however.

“Three weeks after my first procedure my symptoms returned and were much worse,” she said. “It was then decided that they needed to go back and try multiple locations in my neck, groin and central line area for better success and they were able to open the blockage the best they could.” But around five weeks later the same situation occurred again. “I had to repeat the angioplasty procedure for a third time,” she said. “Now, just over six weeks since the last one we are now having to go back in for a fourth time this Friday.”

“We will do another angioplasty and there is a high risk of the chest catheter not working anymore,” she said. “If it does not work my only option will be a femoral catheter in my groin.” That will involve more movement restrictions and she is already heavily restricted due to her many surgeries.

“I am on week five of recovering from the surgery for my new dialysis line,” she said. “No lifting over 10 pounds, no strenuous activity and constant care of the site. Eventually, once it’s healed, I will have to do a week in Sudbury of training and learn how to use my new dialysis machine. I will have it set up in my bedroom to be able to put the machine beside my bed, though I will also need to use my spare room as my storage room for all the boxes of fluid, supplies and more.” The supplies involved are significant.

In the meantime, the high percentage of antibodies in Ms. Casson’s body complicate finding a suitable donor—already a challenging situation. The national and provincial donor lists are for kidneys from donors who have died, but the best option for Ms. Casson would be to find a living donor and/or do a paired match exchange.

“What most people don’t know is that you do not need to be a match to donate a kidney,” said Ms. Casson. “Kidney paired donation, or KPD, also called kidney exchange, gives that transplant candidate another option. In KPD, living donor kidneys are swapped so each recipient receives a compatible transplant, cascading along a line of recipients until a close enough match is made.

For now, without a living donor, my only option is to keep doing treatment while waiting for a deceased donor match. This could take anywhere from five to 10 years.”

“While I and so many others wait for transplants we are slowly dying and it is not an easy thing to go through, for us or for our loved ones,” she said. “Something that has hit me hard lately is that while I hope to receive a kidney, the reality is that a kidney transplant and dialysis are not cures, they are merely treatments. Each step towards a slightly longer life also means so much recovery and so many potential risks. I should be out living a life, not sick, I should be making memories, exploring the world, not feeling like a burden to everyone around me.”

The toll on her mental health is immense.

“My reality is that when I was 24 I was writing my will, making sure that everything was in place if anything should ever happen to me,” she said. “Over the years, surgeries and procedures weren’t easy, but after the last year, I have developed a deep fear now that I have never had before. Whether it is that something will go wrong on the table, or a complication that could happen after, the potential of my high potassium coming back, or having a heart attack at home in my bed where my son could find me, I’m terrified. These are the realities of what I think about daily. These are the things that make it hard to go to bed at night.”

Ms. Casson shares that she fears she is “running out of time and options” but vows to fight on.

“I will keep fighting for my life and for a chance to watch my son grow up” she said. “He means everything to me. I love him with my whole heart.”

The young mother would like to encourage everyone to sign a donor card and consider giving someone the gift of life. “Each donor can save as many as nine lives,” she said.

Being a living donor is a major undertaking for both the giver and the recipient, but it can truly make a world of difference for the recipient’s entire orbit.

Ms. Casson has set up a Facebook page ‘Kidney for Kinga’ where she is sharing her journey and will be providing updates and will answer questions when she is able. “I appreciate everyone who shares or has shared my story, applied to be a living donor, considered being a part of the transplant and has applied for organ donation,” she said. “To everyone who’s messaged me, my friends, family, even strangers, thank you so much.”

In the meantime, Ms. Casson, her son Jack, and their entire family remain hopeful for a Christmas miracle.