Treatment model unique in Ontario

LITTLE CURRENT––Gwekwaadziwin Miikan opened its doors last Friday, May 25 inviting Islanders to meet staff, tour the facility and learn more about the programs offered. UCCM Police hosted a lunch fish fry and Gwekwaadziwin’s culinary specialist prepared a variety of traditional foods.

The first intake for this unique program began Monday, May 28. The intake process is ongoing with a few spots still available for the live in aftercare phase. The land-based training program is scheduled to launch on June 11.

Staff worked closely with the Pine River Institute, a residential treatment centre located in Dufferin County near Shelbourne for youth aged 13 to 19 years who are struggling with addictions or mental health issues. Staff were able to adapt the Pine River model and integrate it into an Anishinabek culture-based program.

The Pine River program was the first of its kind in Canada and uses a four-stage approach to treatment that combines wilderness, residence, transition and aftercare support. “Our program contains three phases: land-based treatment, live in aftercare and community aftercare,” said Sam Gilchrist, executive director.

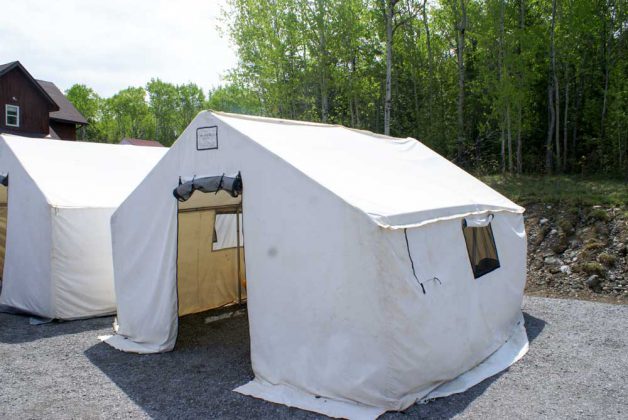

The goal of the three-month long land based treatment (LBT) phase is stabilization, emotional growth, self-management skills and social skills. LBT incorporates outdoor experiential learning, combining therapeutic techniques with Anishinabek culture and conducted completely in the wilderness.

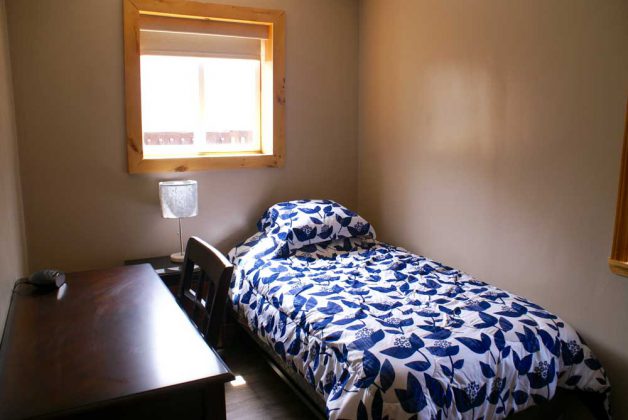

The live-in aftercare phase runs from six months to one year, providing a stable environment for participants to continue developing and practicing therapeutic and life skills. Participants are encouraged to attend regular groups and one-on-one counselling while attending work, school or volunteer opportunities.

The third phase is community aftercare and assists with participants’ reintegration into their community. This phase lasts six months and includes a gradual transition to either independent living or living with their family and full reintegration into their community. Participants will be offered appropriate referrals to community services and peer support groups and staff will maintain contact and offer support via meetings, phone, text message and social media.

“The program has two streams,” Mr. Gilchrist explained, “the Four Directions stream for 13- to 19-year-olds and the Seven Grandfathers stream for 19- to 30-year-olds. Unfortunately, we’re only funded right now for the 19- to 30-year-old stream, the Seven Grandfathers stream, but we continue to advocate for the 13- to 19-year-old stream. All of our programming is based upon best practices and we’ll do some comparative measurements so we can illustrate that we’re doing a good job, that we’ve created a change in individuals and within communities.”

“I came on board in 2015,” he continued. “This wouldn’t have happened without the advocacy of the current chiefs and the past chiefs as well because this advocacy had been going on for five years prior to that.”

Hazel Recollet, chief executive officer of United Chiefs and Councils of Mnidoo Mnising (UCCMM) noted, “He (Sam) knows this place inside and out. We worked really hard to get Sam on board. He took it by the horns and brought this place together. We’ve had lots of meetings with the government to secure a large portion of funding. We’re really proud he got it up and running. All the chiefs of UCCMM worked really hard to make this a reality. I commend them for this. They were very diligent. Joe Hare was instrumental in the development of Gwekwaadziwin Miikan.”

Mr. Hare, a former UCCMM tribal chair and also a former chief of M’Chigeeng First Nation (MFN), explained, “At least six years ago I saw the need to provide better help to people addicted to alcohol or drugs. I thought of an Anishinabek treatment facility which is unique to First Nations in that cultural teachings were the basis. I took it to (MFN) council and they thought it was a good idea. At first it was just for MFN but we could tell as the years went by and the program worked that there was a need to provide these services for the region. We took it to UCCMM so others could have access to the services. The result of that was the development of a steering committee. It took a long time to get support from the government but it finally happened and here we are today. It took all that time. This is the beginning of it.”

Gwekwaadziwin Miikan is located on land owned by Aundeck Omni Kaning (AOK) on Highway 540 west of the main community settlement. The home was originally a private residence but was transformed into a daycare and then a group home following its purchase by AOK. The treatment facility is its fourth incarnation and is where the live in aftercare phase will be housed.

Separate one-time funding dollars were received to get the program set up. Those dollars were utilized to set up the portable building (where the administration offices are located) and get some of the infrastructure pieces completed, including installation of a new septic system. While the facility does have a homey atmosphere, there is a CCTV surveillance system in place. “The safety of our participants and our staff is a priority,” said Mr. Gilchrist.

The portable will also be used as a meeting space. “Essentially our land based treatment counsellors are out on the land seven days at a time and then they’re off for a couple of days,” continued Mr. Gilchrist. “Then they’re in here so we can have our clinical meetings. We can have meaningful dialogue about the participants that are on the program and how we can best envelope them within a holistic model here.”

Inside the multi-level facility are two multi-purpose rooms; kitchen, dining and laundry facilities; five single occupancy rooms on the lower floor for females; and three double occupancy rooms on the upper floor for males.

“Every part of the program is experiential so we’ve got room for our participants to sit down but also for our staff to sit down with them and really work on that therapeutic alliance and building relationships on every level of the program,” explained Mr. Gilchrist. “We’re here role modeling about how we want our participants to act and so our staff is acting in those appropriate ways on every level and something as simple as eating meals as well.”

The room on the upper landing is a multi-purpose TV room. “It’s where our traditional knowledge keepers work out of,” Mr. Gilchrist said. “We’ve been very fortunate in that we’ve got terrific traditional knowledge keepers who have been able to build up our staff’s knowledge base and of course they’re going to be able to work with our participants as well. So we’ve been doing a lot of work with regards to learning about medicines and those different culture pieces as well.”

“Essentially, we work from the client-centred model of care. We’re not trying to come at treatment with a cookie cutter approach. We’re looking at each participant as a unique individual and trying to create a treatment plan that fits their unique needs. Of course we’re also using trauma informed practice to understand the needs that might need to be meet due to acute, chronic and intergenerational trauma and we’re also utilizing what is called a maturity model. Essentially, the tenets of the maturity model are that if something has occurred (such as trauma) to stagnate an individual’s maturity, we’re working with them on their own identity and growing that maturity to a more socially acceptable level.”

During the open house, staff members provided skills demonstrations, shared stories and sang songs in tipis as well as answered questions about the program. Team leader Matt shared, “The amount of skillset that we have in each of our staff is very unique. You won’t really see this at most of the basic or standard treatment programs. You need to know your survival skills. You need to know how to respond in dangerous situations and you can’t really have a rigid structure because you need to be adaptable to whatever Mother Earth gives you that day. We have no idea what we’re going to face on a day-to-day basis as far as the natural environment goes so we’ve given a lot of flexibility to the LBT counselors within the program we’ve designed. That being said, there are things that we plan on doing. The Redpath model, for example, which is the addictions counselling component, and there’s also the survival component on top of that.”

The Redpath model is a unique program that was developed by Peggy Shaughnessy, a PhD student from Trent University in Peterborough. Ms. Shaughnessy piloted a needs assessment through the Psychology Department and the Emotional Health Lab with Dr. James Parker at Trent, working with inmates at Kingston Penitentiary and Warkworth Institution. From that, she created Redpath which looks at emotional and social competencies and gets to the root of the problem based on the premise that addiction is not the problem, the problem is why people are addicted. Traditional treatments focus on behaviour avoidance while Redpath looks at the root causes of the behaviour.

The staff is very excited to get out there and apply their training, said Matt. “I’ve been here for five or six weeks at this point. We jumped right into it. Some people have been here longer, maybe three or four months. It’s just been non-stop going until we had the full complement (of 23 full-time staff). We’re really banking on a strong support staff as well for the casual pool just to ensure we have the supports required to give our staff that kind of relief as needed as well. So we’re there, we’re ready to go.”

He continued, “It’s really being approached in a good way. I’ve seen, just in my own experience, a number of programs that try to sprinkle in their cultural component but Sam has done an amazing job of making that the foundation of the program. We’re trying to start everything in a good way from our medicines to just even in the way we communicate and applying those kind of Grandfather teachings and being open to that. It’s just being done with good minds and good hearts. It’s really good to see that as the foundation (of the program) as opposed to just another mainstream program with a little bit of culture sprinkled into it. I think that will be the biggest difference in the success of the program.”