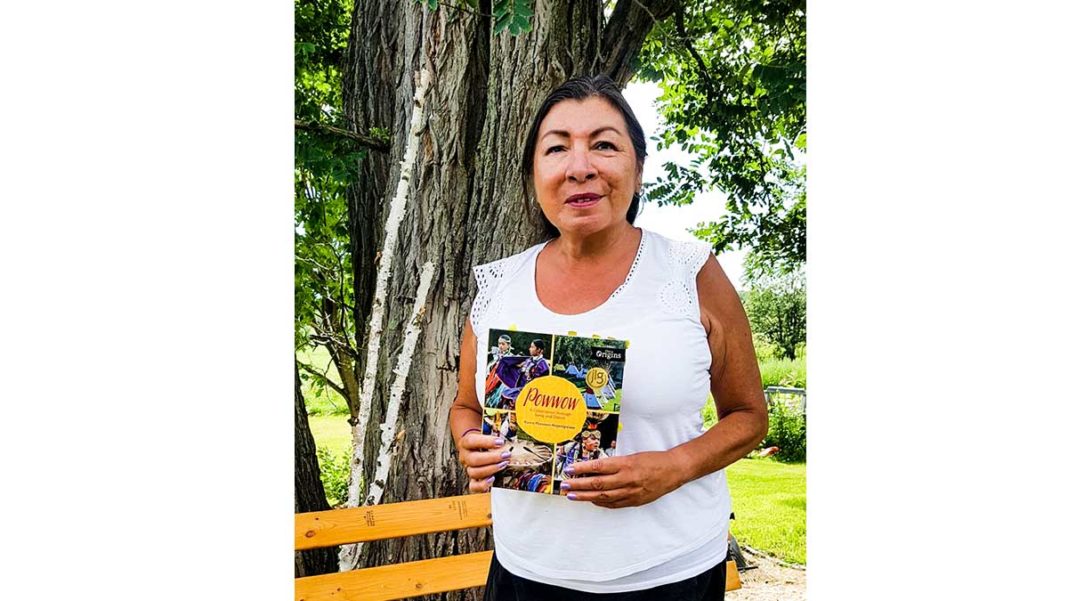

TORONTO – The Expositor had the opportunity to congratulate Wiikwemkoong author Karen Pheasant on being awarded the $10,000 Norma Fleck Award for Children’s Non-fiction for her book ‘Powwow: A Celebration Through Song and Dance, by Karen Pheasant-Neganigwane (Orca Book Publishers).’

Ms. Pheasant said that she was honoured and pleased to receive the award. “I was so happy to learn that I was on the short list,” she said. “To hear that I have won is wonderful and humbling.”

Canada’s non-fiction books for young people are internationally renowned for the superb quality of their text, illustration and design, notes the award committee website, which notes the Norma Fleck Award for Canadian Children’s Non-Fiction was established by the Fleck Family Foundation and the Canadian Children’s Book Centre on May 17, 1999 to recognize and raise the profile of these exceptional non-fiction books.

The $10,000 Norma Fleck Award is the largest of its kind in Canadian children’s books and is considered to be one of Canada’s most prestigious literary prizes. The Norma Fleck Award is exclusively a non-fiction prize; most other Canadian children’s book prizes either evaluate fiction and non-fiction together, or don’t award non-fiction.

The Norma Fleck Award for Canadian Children’s Non-Fiction is named after Dr. Jim Fleck’s mother, Norma Marie Byrnes, who fostered a love of reading in her children and grandchildren. Norma worked as a nurse until she married Robert Douglas Fleck in 1930, and raised three sons during the Depression with energy, good spirits and creativity.

A lifelong avid reader herself, Norma read to her children and encouraged them to read, notes the website. “Mother believed that quality reading enriches one’s life,” said Jim Fleck. “She would be greatly pleased by this award in her name.” Norma Fleck died in 1998 at the age of 92.

Ms. Pheasant said she was inspired to write the book as, “Often society has a romanticized understanding of the who, what, how and where of cultural practices, not disputing that it has artistic beauty and showmanship, but its roots are based on challenging colonialism. Realize that in earlier history, we were not allowed to leave our reserves without government permission. Recall that many cultural items were appropriated, became museum pieces and society at large was preparing for us to become a ‘vanished’ nation.”

She went on to note that, “Teaching at the University of Alberta in the faculty of education to preservice teachers for six years to status quo Canadian/Albertan students provided an insight to the extreme limited knowledge that a typical citizen has of Indigenous peoples. Some think we are one nation, one language, one people. They don’t realize the many territorial /nationhood differences that exist between nations. Students have shared to me that they “feel so ripped off” at not being educated about Canada’s actual truth about Indigenous peoples. My first chapter is on colonialism.”

Ms. Pheasant went on to say that, “For my children, grandchildren, adopted children, they are all aware of the political, social, familial and cultural wealth that resides in the lifestyle of powwow culture. It goes beyond a weekend of song and dance. Each tribal nation carries their own distinct, separate cultural practices, from the food, the dance, to songs so that the value of each nation’s uniqueness is sought; so that the strength of each nation is not lost but investigated.”

“That powwow culture finds its way to the thousands and thousands of lost identity individuals (due to colonialism and government policies that removed children from their families) and find healing from the dances and songs,” she said. “May this book be a bridge of understanding for all of society, to have peace, justice and harmony within all of society.”

Ms. Pheasant notes that she is consumed of “an intense wanderlust, which in this time of the pandemic we are in is pretty tough. Powwow life provides a nurturing salve to my mind, body and spirit.”

She said that diversity is important in children’s literature. “Mino bimaadiziwin is an Anishinaabe term,” said Ms. Pheasant, “meaning ‘good life’ principles. In short, that means seeking, finding and doing what everyone has been blessed with. I don’t believe we were intended to be an assembly line of human beings. What makes you distinct and unique? What stirs your passion? What brings you joy? Seek that, be that and celebrate it, in whichever way speaks to you in a healthy way. Particularly as a child, before society has distracted you, what does your heart tell you?”