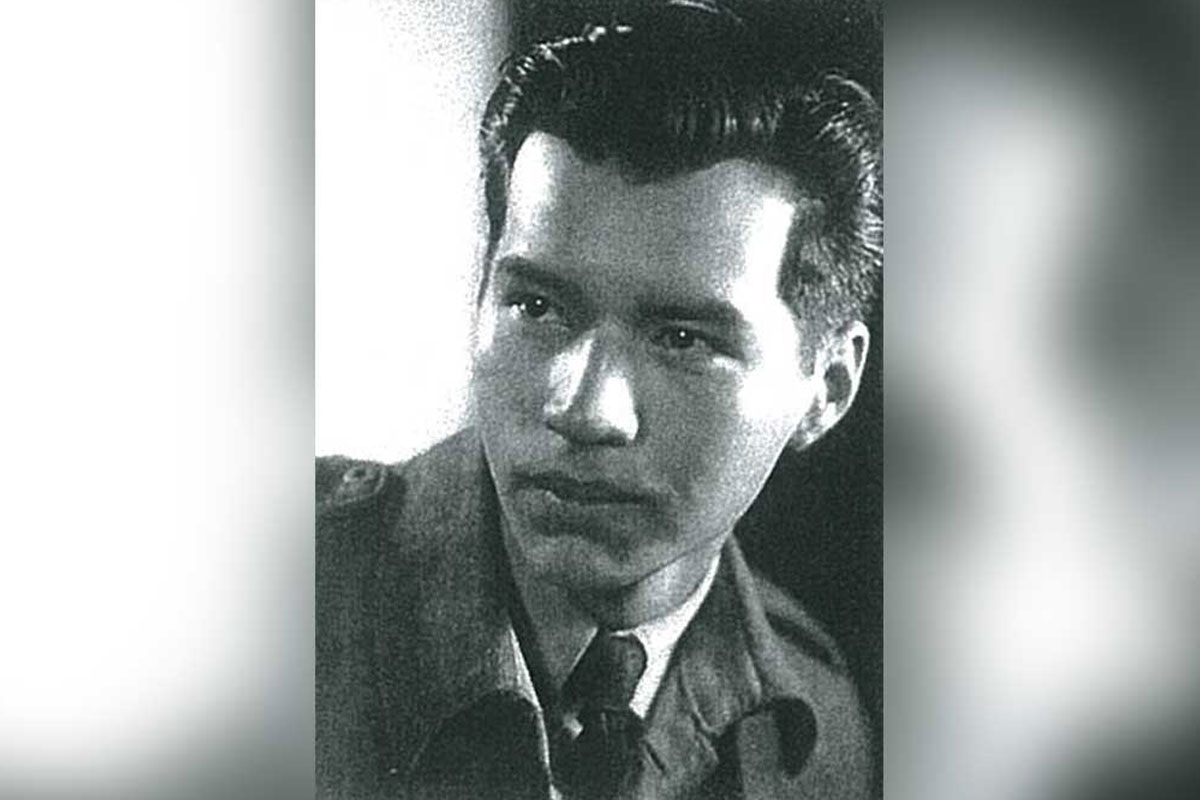

ARIZONA—M’Chigeeng band member Justin Roy is Manitoulin Island’s last known remaining Second World War veteran. Nearing the centenary mark, Mr. Roy now makes his home in Arizona, but in 1943, at age 19, he was a strikingly handsome young Anishnaabe with a hankering for adventure. Like many young men on Mnidoo Mnising he travelled south to Toronto to enlist in the Canadian Forces.

He originally wanted to join the paratroopers, like fellow M’Chigeeng band member Rene Cada baa would later do, or possibly the air force, but that dream was derailed by a lack of education. So, Mr. Roy settled on joining the regular army and was assigned to the 3rd division of the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

Following his initial training at the CNE grounds, Mr. Roy would eventually find his way to Britain for advanced training, where life was relatively quiet and uneventful—at least until June 6, 1944, D-Day. England was a bustling hive of activity in the weeks leading up to the first week of June as the western Allied nations prepared to assault Fortress Europe so everyone, including the Nazi defenders, knew an invasion was imminent.

“We were told the day before (that they were to be deployed) and we knew that something big was going on,” he explained to The Expositor’s Alicia McCutcheon during a previous visit home.

In the early morning hours of Tuesday, June 6 Mr. Roy and his compatriots boarded the vessels that would take them into the maelstrom that was the largest amphibious invasion in history. Waiting for them were the sights of the German forces that had overrun Europe just a few years before.

“When you got off that ship, down that rope ladder, your life expectancy was 15 minutes,” Mr. Roy recalled. “The water was so rough, sometimes it was over our heads.”

The objective set for the Second Division that day was a point of land some seven miles inland, and the Canadians were the most successful of the forces to land that day, but it came at a terrible cost. “There were 45 of us left out of 200,” he said, adding that the paratroopers who landed ahead of his group were entirely wiped out.

The Canadian 3rd Division suffered the bulk of the 950 D-Day casualties endured by the 21,400 Canadian troops that landed on Juno Beach.

The fighting was intense and brutal. At one point, separated from his unit, Mr. Roy crawled under a destroyed tank and lay there for two days. He and his unit would go on to spearhead the assault seven times.

“I never thought I’d get out of there alive,” he recalled. “Everyone was my age, 18 or 19, laying out there in the field. They were crying and yelling, but there was nothing you could do.”

During the next 31 days, Mr. Roy said he saw and did things that have kept him busy for the last 70 years trying to forget. He recounted a time when his unit disabled a German tank by shooting out the engines. Three Germans escaped from the ensuing blaze, but the driver and co-driver were trapped inside, bleeding out and burning alive.

Only their screams ever left that tank. Mr. Roy and his fellow soldiers could not save the German tankers, so one of the men tossed two grenades inside and closed the hatch.

The soldiers considered it to be the most merciful thing that could be done.

“To me, that was murder, but what else are you going to do?” he asked.

After 31 days of pushing into France it was Mr. Roy’s turn to join the ranks of the wounded, taking a shrapnel hit that pulled him out of the front lines.

“I wanted to go back to the front lines, to be with my buddies, but they wouldn’t let me,” Mr. Roy recalled. He would spend the remainder of the war assigned as a driver for senior officers.

Mr. Roy stayed on with the Occupation Forces following the end of the hostilities. Eager to see the world, he took a leave of absence and spent a year working his way around Europe while riding an old Norton motorcycle through France, Germany, Holland, England and Scotland and finding work in restaurants, shipyards and hospitals to see him through.

When he finally headed for home, he sailed aboard the Queen Mary, arriving in New York City before the train to Toronto and then on to Sault Ste. Marie.

For many young men returning from service overseas, their job was waiting for them when they got home. That was not to be for Mr. Roy. After years of camaraderie in the ranks and the open acceptance he had experienced in Europe, the sting of racism he found upon his return was especially harsh.

Mr. Roy recalled to The Expositor the moment, after donning new Levis and shirts instead of his familiar khaki, the still young Indigenous man joined some old comrades for a drink in a local bar. The barkeeper wouldn’t serve him, however, as he was “an Indian.”

“I just broke down,” he said.

Mr. Roy went on to try his hand at farming in M’Chigeeng, but micromanagement by Indian Affairs doomed that venture. The racism he experienced in the country in whose defence he had laid his life on the line continued to dog him over the next seven years he was employed Falconbridge in Sudbury.

As the first First Nations man in his particular mine, Mr. Roy found himself assigned the dirtiest jobs, “but I didn’t mind,” he said. “I got a paycheque.”

Still, the time came when he decided to try his hand south of the border and, together with his late wife Joyce, travelled to the US, where he continued to work in the mines, but he eventually had to give that up due to a shadow doctors discovered on his lungs. Even there, throughout his time in the US, Mr. Roy continued to experience racism.

He eventually started a successful air conditioning and sheet metal business—an occupation he continued to practice for half a century, only giving it up when his memory began to become a challenge. “I had a pretty good life once I started contracting,” he said.

Mr. Roy is a member of the local chapter of the VFW (Veterans of Foreign Wars) and until recent years, he would attend Veterans Day (Remembrance Day) services in Mesa.

Still, through it all, Mr. Roy has been dogged by post-traumatic-stress disorder (PTSD).

“Sometimes your nerves just get the better of you,” he said. He admits to having barbed wire all around his shop, a result of the PTSD. It was while receiving counselling for his PTSD that Mr. Roy met his second wife, Barb. He credits her with helping him deal with his stresses immensely.

Approaching 100, Mr. Roy was unable to join any of the many junkets to take part in the D-Day commemorations in Normandy this past week due to his health. He recently suffered a fall and broke his hip.

“I had hoped to go to Abilene (for the observances being held there),” he said, but that was also not to be in the cards.

Instead, Mr. Roy, like many of those veterans remaining, watched the events unfold on television.

Mr. Roy said that he hoped to be able to return to Manitoulin to celebrate his 100th birthday this coming fall.

Until then, he likes to sit on his porch and get some fresh air in the evenings—not in the midday, however, as the temperatures in Arizona right now are north of 110 degrees Fahrenheit (43 degrees C).

We look forward to seeing Mr. Roy again.

Lest we forget.