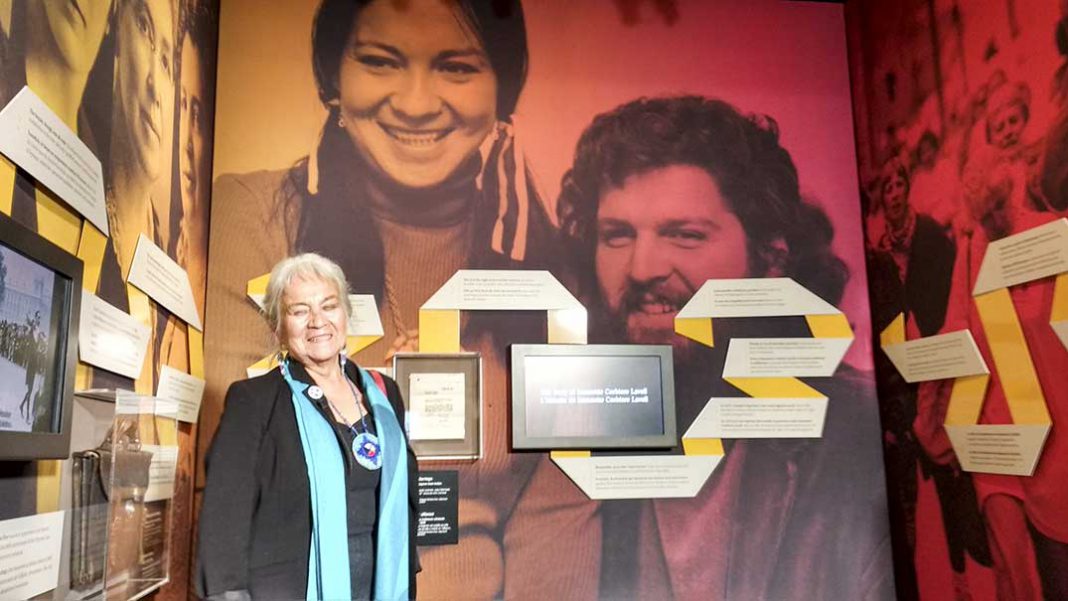

MANITOWANING—Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory’s Jeannette Corbiere Lavell, Keewednanung (North Star) in her native Ojibwe, is no stranger to honours. She is being featured in the new Canadian Museum of Human Rights in Winnipeg and even has an award named after her (the Ontario Native Women’s Association established the Jeannette Corbiere Lavell Award in 1987 “to be presented annually to a deserving Native Woman demonstrating the same qualities and dedication as Jeannette”). Later this year, though, Ms. Corbiere Lavell will be joining the ranks of the members of the Order of Canada as a 2018 inductee.

The award came as bit of a surprise to the longtime Anishinaabe rights activist, if not to any of those who have followed her long and storied career.

“I haven’t been recognized lately about anything,” she laughed when contacted at her Manitowaning home following the announcement of her impending elevation to the Order of Canada. Ms. Corbiere Lavell is very active as an environmentalist these days, lending her talents and wisdom as part of the struggle to protect water.

The story of her rise to activism and leadership that led to the Order of Canada honour is one that speaks to Ms. Corbiere Lavell’s long vision and tenacity.

Born Jeannette Vivian Corbiere in Wiikwemkoong on June 21, 1942, Ms. Corbiere Lavell is a an Anishinaabe kwe community worker who has spent much of her life’s work focused on women’s and children’s rights. Her parents were Adam and Rita Corbiere and she came by her activism quite naturally. Her mother was a school teacher, who became one of the founders of the Wikwemikong Powwow—generally recognized as the Grandmother of Powwows in Ontario. While she learned English from her mother, her knowledge of her Native language, Ojibwe, came courtesy of her father.

Ms. Corbiere Lavell completed Grade 10 on Manitoulin but she moved to North Bay to complete her high school before attending business college in that city. After graduation, Ms. Corbiere Lavell worked for the Native Canadian Centre of Toronto as an executive secretary and became associated with the Company of Young Canadians, giving her an opportunity to travel around the country. In 1965, she was named Indian Princess of Canada. Those were different days.

By 1970, Ms. Corbiere Lavell had married Ryerson film student David Lavell, a non-Indigenous man. That decision was to have a defining impact on her life in more ways than one.

“One day, a letter arrived in the mail informing me that I was no longer an Indian,” she recalled. Her official “Indian Status” had been revoked because she had married a non-Native. Before that moment, Ms. Corbiere Lavell had been recognized a full-status Indian under the Indian Act.

That notice from the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development stated that she was no longer considered an Indian according to section 12 (1) (b) of the Indian Act. It cited section 12 (1), which says that “the following persons are not entitled to be registered, namely, (b) a woman who married a person who is not an Indian, unless that woman is subsequently the wife or widow of a person described in section 11.”

That letter left her in shock, but she soon shook it off and got to work on her struggle to reclaim her heritage. In 1971, she launched a challenge to the Indian Act section that was attempting to rob her of her heritage.

Had she been a man when she got married, Ms. Corbiere Lavell would not have lost her status.

She decided to challenge the Indian Act on the basis that section 12 (1) (b) was discriminatory and should be repealed, according to Prime Minister John Deifenbaker’s 1960 Bill of Rights. It was the first case dealing with discrimination by reason of gender.

Ms. Corbiere Lavell described her early experiences in the Canadian courts of the day as an initiation into the underlying racism that existed then in mainstream society and perhaps, almost as devastating, initiated her to the sexist reaction of the First Nations advocates at the time, her own people, which she described as an even more devastating blow.

“The judge in the case, a Justice Grosberg I think it was, was putting our women down,” she recalled. “He said, ‘we know what Indian women are like, you should be glad a white man married you.’ That was what it was like in the courts in the early 1970s.”

It was little surprise, then, that the first decision went against her.

But that setback did little to deter Ms. Corbiere Lavell. Soon she and her lawyer (the not-yet-famous Clayton Ruby) brought the fight to the Appeals Court, winning a 1973 unanimous decision at the Ontario Court of Appeals. Unfortunately, politics and government pressure led the federal government of the day to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada where she and fellow appellate Yvonne Bedard lost their case on a 5-4 decision.

“It was devastating,” she recalled of that loss.

The issue was far from semantic. When a Native woman lost her Indian status, so did any children of the marriage. “That meant they could no longer live on the reserve and lost the right to own land or inherit family property,” said Ms. Corbiere Lavell. “They could not receive treaty benefits or participate as elected members of band councils, political or social affairs in the community and they lost the right to be buried in cemeteries with their ancestors.” But Native men who married non-Native women were not deprived of these rights and their wives and children were given Indian status. It was blatantly a sexist situation.

There were an estimated 4,605 Indian women who were enfranchised (recognized as Canadian citizens—thereby losing their Indian Status) by marrying white men between the years 1958 and 1968.

During her battle, Ms. Cobiere Lavell sought the support of the Union of Ontario Indians (UOI), now better known as the Anishinabek Nation, but the grand chief at the time was apoplectic when he heard about her crusade. “His name was Wilbur Nadjiwon and he got very upset with me,” recalled Ms. Corbiere Lavell. “He said ‘oh no, this is our tradition’ and he began berating me. We were not even allowed to present to the UOI. I found out later that he had married a white woman, so he had some interest in keeping it the way it was.”

Ms. Corbiere Lavell did find strong support closer to home—and at home.

“The chief in Wikwemikong at the time, John Wakegijig, was very supportive personally when he learned of what I was doing,” she recalled. “It did not go before the band council at the time because it was a personal initiative on my part.”

Her father, the late Adam Corbiere, told her to follow her heart and passion. “It doesn’t matter what other people think,” she recalled him telling her after the UOI rebuff. “If you believe in what you are doing, then you go ahead and do what you think is right.”

It wasn’t until a later court challenge, which her own battle had inspired, that Ms. Corbiere Lavell’s status was reinstated—sort of.

Sandra Lovelace, following in Ms. Corbiere Lavell’s footsteps, brought the case of status removal to the United Nations International Human Rights Commission, which ruled in her favour. In 1985, Section 12 of the Indian Act was repealed.

“It’s still not over,” she noted of that fight. Although Ms. Corbiere Lavell did eventually regain her “status,” she still has not regained the status level that she had before her marriage.

“I still don’t have 61A,” she said, referring to her previous status level. Her status is now 61B. “That means my children get 61C.”

Ms. Corbiere Lavell cited the work just before Christmas of Canadian Senator Lillian Dyck, among others, who have a campaign seeking to redress the remaining vestiges of sexual discrimination in the Indian Act. “She is pushing for 61A all the way,” said Ms. Corbiere Lavell.

These days, Ms. Corbiere Lavell is still keeping her hand in and is active in campaigns to help protect Canadian water resources.

She has served as president of the Native Women’s Association of Canada and founded the Ontario Native Women’s Association of Canada; served as a cabinet appointee on the Commission on the Native Justice System, was president of the Nishnawbe Institute, as well as the president of Anduhyaun Inc., an organization that “strives to support Indigenous women and children in their efforts to maintain their cultural identity, self-esteem, economic, physical and spiritual well-being.”

Ms. Corbiere Lavell earned a teaching degree from the University of Western Ontario, has worked as a teacher and school principal, co-edited the book ‘Until Our Hearts Are On the Ground: Aboriginal Mothering, Oppression, Resistance and Rebirth.’

In 2009, Ms. Corbiere Lavell was honoured nationally, by then Governor General Michaëlle Jean, as one of the first recipients of a Persons Award, an honour that recognizes those who fight for women’s rights in Canada. These Governor General’s Awards are in Commemoration of the Persons Case and were created in 1979 to mark the 50th anniversary of the groundbreaking Persons Case, which changed the course of history for women in Canada. The award was named for the Famous Five, five Alberta women fought for women’s rights. Those five pioneering women were Emily Murphy, Louise McKinney, Irene Parlbt, Nellie McClung and Henrietta Muir Edwards.

In 2016, Ms. Corbiere Lavell received an honourary doctorate of laws from York University—so “recently” may be considered a relative term.

Her daughter, Dawn Harvard, has followed in her daughter’s footsteps as the youngest-ever president of the Ontario Native Women’s Association.

It was the ONWA that established an award in honour of Ms. Corbiere Lavell in 1987, “to be presented annually to a deserving Native Woman demonstrating the same qualities and dedication as Jeannette.”

“We have accomplished a lot,” said Ms. Corbiere Lavell looking back on her battle for equal rights and to regain recognition of her heritage. “We have taken many positive steps forward, but there is still a long way to go.”

Some time later this year, Ms. Corbiere Lavell will be recognized for her steadfast dedication to the cause of Anishinabe-kwe rights, but although she spends a fair bit of her time enjoying her grandchildren these days—it is for their future that she has no intention of stepping back from her fight.

“We have a duty to those who come after us,” she said.