by Kate Thompson

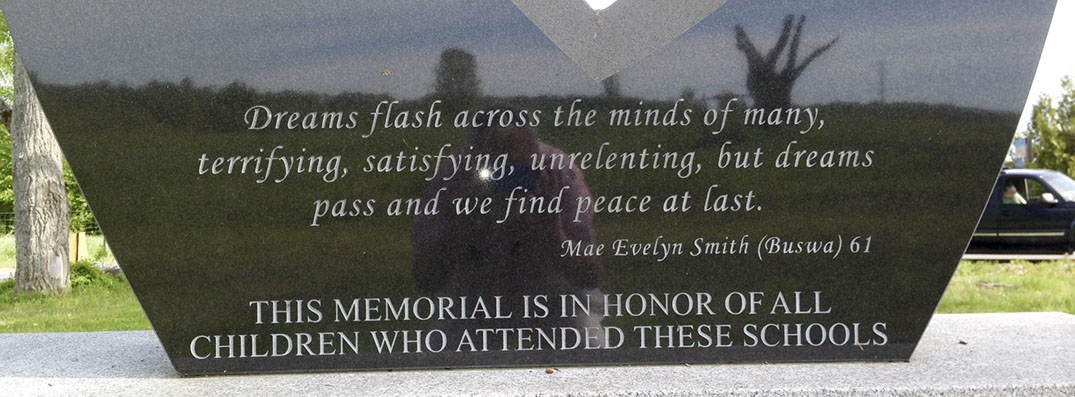

OTTAWA—On Sunday, May 31 several thousand people of many nations walked together for reconciliation and healing, making their way from Gatineau, Quebec, past Victoria Island, past the Parliament Buildings and on to Ottawa City Hall. This walk marked the beginning of new opportunities for more open relations between Canada’s governments, churches and citizens and the tens of thousands of First Nations people who were deeply damaged by purposeful and prolonged efforts to kill peoples and cultures. Organized as the closing of one phase and the beginning of another, the Walk for Reconciliation and other events that took place from May 31 to June 2 served as a transition in the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). The Commission spent its six-year mandate gathering stories by First Nations survivors of Indian Residential Schools and collecting historical documents that chronicle the development and growth of the schools across Canada.

photos by Peter Baumgarten

Those four days of events mark another step out of Canada’s dark past of systematic annihilation…into sporadic and slowly growing societal and official acknowledgement of Native people’s worth and autonomy…and into what can be shared understandings of what it means to be a person, a citizen, a nation.

My friend and travelling companion, Christianna Jones of Wikwemikong First Nation, expressed her reasons for going to Ottawa last week. “I am a second generation person whose life has been impacted and shaped by the fact that my father was forced to attend the Garnier School in Spanish. The walk was for him and for many others who were not able to participate. It was for the children and grandchildren of those who attended residential school, who couldn’t be raised by parents who were connected to their culture and language. The stories needed to be told by those who attended a school and heard by those who did not.”

When my friends and I gathered at Victoria Island to honour those stories together, thousands more were walking toward us from the starting point at a Gatineau secondary school. We stood in small groups and milled around in the cool sunshine, waiting for word from someone that the walkers were getting closer to us, so that we could join them. We chatted with a man who had flown for five hours from a reserve in northern Quebec to be there and also with a young non-aboriginal woman from the Ottawa region who wanted to learn about the events of the day and the TRC. After a while longer, and after talking with one of the orange-shirted volunteers, we made our way across the street to watch for the walkers ourselves.

The highlights of that wait were, for me, the chance to hear Chief Wilton Littlechild, one of the commissioners of the TRC, talk about his experiences at residential school, which he balanced beautifully with his positive approach to reconciliation today. Chief Littlechild spoke about what it was like to be taken from his home and left on a cold January day in a place full of strangers who spoke a language he did not know. He knew his brothers and sisters were at the same school, but they were not allowed to be together, so he, like so many aboriginal children, was cut off from everything he had known up until then. He was forced to stay in that school for 14 years. Yet even so, he was able to stand up on that podium and speak of hope and the strength of his people.

The other high point in those waiting moments was a friendly conversation I had with a young Cree woman from Moose Factory who had travelled to Ottawa with her little son and her mother to participate in the events of the week. Both encounters exemplified what the week’s activities were all about–a First Nations man being able to speak his truth to ears willing to hear, and a friendly exchange between two women of two different races about the ordinary things of life, all within a context of hope.

As word spread that the walkers from Gatineau were coming, everyone in the little park hurried up a small rise to the street, and there they were–thousands of people, filling the wide bridge and carrying banners, placards and community flags. People of many races and colours and ages came along, smiling and talking with their neighbours, singing and drumming, as those of us on the sidelines joined them. The sight and sound of so many people walking and talking, moving together was powerful and invigorating. As we kept going, people came out of churches and other buildings to wave or give a thumbs-up. Camera crews darted in an out, sometimes interviewing a walker or simply recording the crowd for news broadcasts and historical records.

One of the walkers we passed was Premier Kathleen Wynne who grinned and said, when I congratulated her on being there, “I wouldn’t have missed it for anything!” I wondered how many other politicians were there, cognizant of their role in the hoped-for changes to come. But this did not feel like a day for jaded reflections on political shortcomings, and so, turning my full attention back to the power and emotion of the day, we continued on our way.

By the time we got to Marion Dewar Plaza (Ottawa City Hall), many seemed happy to find a rare shady spot and a park bench, to line up at the food and water vendors and to rest weary feet. Many elders were already there, scattered around the plaza and seeming to me to anchor the proceedings. For we were not done yet. We were treated to a short and enjoyable speech by Wab Kinew, noted journalist and honourary witness for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. As recounted by Christianna Jones, “He announced the names of many First Nations of Canada and people proudly shouted or raised their hands to make sure others knew they were there. So, many nations were represented from across Canada. They travelled so many miles to be there and show support.”

Perhaps the most thrilling part of the day, aside from the walk itself, was the opportunity to stand within a few yards of the Honourable Justice Murray Sinclair and hear his stately and humorous words. A superb speaker, Justice Sinclair talked about the many horrors expressed in the thousands of stories told by former students of residential schools and written in the documents the Commission gathered. With great dignity, Justice Sinclair spoke of his hope for the future. “Don’t just believe that reconciliation will happen, believe that it should happen.” Wild applause followed this statement. “Reconciliation will not happen in my life time, and reconciliation will not happen in my children’s life times, but it will and can happen in my grandchildren’s lifetime.” More thunderous applause. “Seven generations of children went to Indian Residential Schools. Seven generations. If it had been ‘only’ 20 or 30 years, one generation, our people could probably have made it through, because the children would have returned to villages where their languages and customs and ceremonies were still strong. They could have healed. But seven generations was enough to do great damage to those languages, customs and ceremonies. Yet we are getting those back now.”

As has been said by others, we are all treaty people. European ancestors entered into treaties with First Nations ancestors, sometimes honourably, sometimes not. Today the affects of dishonourable choices by governments, churches and individuals can be felt in every community across the country, and not only the reserves. We have all been affected by Indian Residential Schools and their terrible legacy.

Like so many governments around the world, Canada’s leaders have tried to force indigenous people into a mold based on a Eurocentric, linear world view with no regard for the ways of those they twisted. However, due to the actions and voices of those same people, a dialogue was opened when many First People refused to step down, to accept devaluation any longer. Out of that dialogue grew the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a way forward for this country to take responsibility for that mistreatment and to support healing and reconciliation among the many people of this country.

photos by Expositor staff

Sunday, May 31 was wonderful and powerful, as I’m sure the next three days were. But the point is not really just that one day or even the one huge report that will be issued by the TRC, any more than the purpose of a pencil is to make one dot on a piece of paper. The pencil is intended to start with a dot and then keep going—into lines and words and pictures. And so it is with the Walk for Reconciliation. It was a beginning of a new phase, as much as or more than the ending of former ones.

The TRC and the events of last week are signs of hope, to be sure, but it seems that the real work must be between one individual and another through learning about one another face-to-face at work, at home and in public spaces like grocery stores and schools and hospital waiting rooms. Get to know your neighbour. Make the time. Give your mind and your heart and spirit to that practice, and the TRC’s good words and powerful intentions will be helped to take root.

As Christianna Jones clearly states, “The truth is out, and now it is time for reconciliation.”