KAGAWONG—While it is one of the most gut-wrenching stories Mike Strobel has ever heard in his over 40 years as a journalist, columnist and editor, the story of the tragic The Rhu (in which four people from two families lost their lives) through the words of one of the survivors, Jim Huffman, lived through is also about courage and redemption.

“I’m here to do present the tragedy part of the theme ‘Tragedy and Triumph on Lake Huron,’ said Mr. Strobel in a presentation he made at the annual History Day in Kagawong event August 8.

“About 12 years ago, I wrote a column in the Toronto Sun about getting my leaky old canoe blessed at the little white church just down the road from here (Park Centre) and I made reference to the long history of shipwrecks in these waters, and I mentioned the Rhu. Just a couple of lines in passing,” said Mr. Strobel. “I knew very little about the wreck, really. Just that it happened in 1965 off my shore at Maple Point, about 10 kilometres from where we are now and that four passengers on the cabin cruised died, including two little girls and their mom.”

“One of the people who read that column, in Toronto, was Jim Huffman, the dad of those two little girls and the husband of their mom, a man who survived the wreck, but who lost his whole family in the process.”

“Jim got in touch and wanted to talk about, after all these years, nearly half a century at that point. He had a new family with two grown kids and even they knew precious little about what had happened all those years ago in the North Channel,” said Mr. Strobel.

“So, a (Toronto) Sun photograph and I went up to the long-term care centre on Christie Street in Toronto where Jim was in the later stages of Parkinson’s disease,” said Mr. Strobel. “We talked for more than one hour. You could barely hear him, but, believe me, we hung on every word. I think it’s one of the great tragedies of Manitoulin Island even of the North, something Shakespeare might have written. It has all the elements, including mystery, awful choices, bad luck, struggle, sorrow, and guilt. Lots of guilt, then finally, some redemption.”

Mr. Strobel explained that in August 1965, so almost 60 years ago, the Rhu with her six passengers was en route from Little Current to Gore Bay on a weekend outing when she ran aground on Middle Bank, which is a shoal just west of Mudge Bay. Carolyn (Mr. Strobels’ wife) and I can see that shoal from our place on McQuarrie Road. “Onboard, all from Sudbury, were Jim and Shirley Huffman, 30 and 31 years of age respectively, their daughters Catherine, four, and Karen, 2, and their friends Wynn and Bonnie Rhydwen, 50 and 43 years old . Over the next two days, a storm blew up and they roped themselves together and abandoned ship, four of the six died, both of the little girls and Shirley and Wyn. Jim and Bonnie, exhausted and heartsick finally washed up on a tiny island after 16 hours in the water.”

“So, there you have the headline news version of the Rhu story. Now, let’s get into more details. First, let me introduce the characters in this great tragedy, starting with the boat itself,” said Mr. Strobel.

Mr. Strobel showed a photo of the Rhu, as the Arno. The previous owners found the Arno too difficult to manoeuvre through the shallows around their cottage, so they sold the Arno to the Rhydwens and Huffmans early in1965 and she because the Rhu.

He showed a video of a sister boat of the Rhu, another Chris-Craft Cruiser Deluxe which had been constructed a few years earlier. “She’s a beautiful boat, 26 feet long. All gleaming mahogany from the Philippines. Normally, she slept four, though the Rhu had two extra little bunks for the girls.”

“An odd detail was that the draft on the earlier boat was 20 inches, but by the time production got to the Rhu, the bow had been slightly rounded, and the craft was 22 inches,” said Mr. Strobel. “God only knows if those two inches would have made a difference given the fate that awaited the Rhu and her crew.”

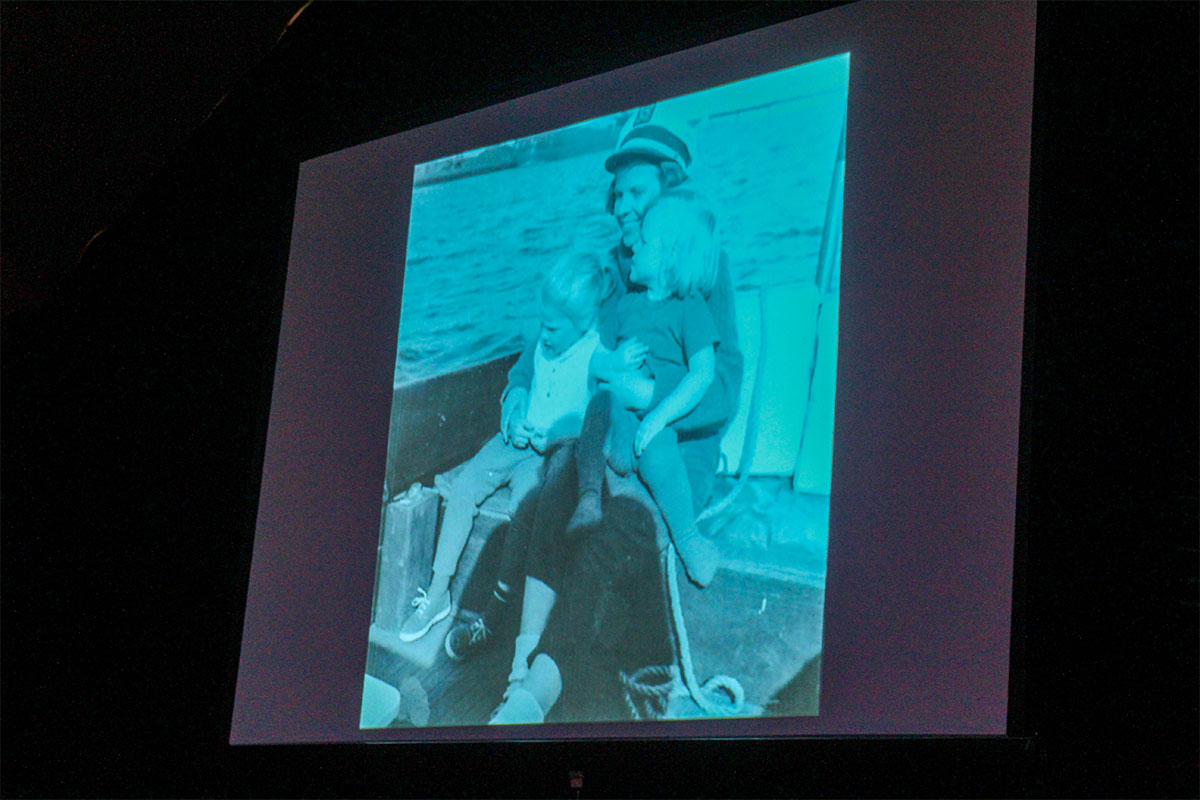

He then presented a slide photo of the six people on board the Rhu for her final voyage. “Of the two families, I now the most about the Huffmans,” Mr. Strobel said in showing a photo Jim Huffman and Shirley Colling at their wedding at Lowville, Ontario, now part of Burlington, in 1957. “This is her as a bride, with little sister Pauline as maid of honour. I had a nice long talk with Pauline, who now lives in Maryland. She’s in her 80’s. She told me how Shirley excelled at piano, and won high school awards in physics, music, and art. After all these years, it’s pretty clear the two sisters were exceptionally close, and Shirley remains a big influence in Pauline’s life.”

Mr. Strobel said, “Pauline told me, ‘She liked having me around, and that’s not always the case with a big sister and little sister. She was someone I wanted to be. I looked up to here. She was an ideal, and she had naturally curly hair and I didn’t.’ Shirley had a Manitoulin connection long before the Rhu having a summer job as a teen at Treasure Island, the resort you probably know on Lake Mindemoya.”

“Shirley and Jim met at the University of Toronto,” said Mr. Strobel. “Jim was from Leamington. They were a bit of an odd couple, sort of Mutt and Jeff. Jim was this burly teddy bear of a guy and Shirley this beautiful blue-eyed and very popular girl. Pauline says Jim was the husky, protective type of man and Shirley like that. They also bonded over shared interest in music, and also in the north. Shirley had summer jobs at northern resorts. Jim was a boater and outdoorsman. And they both became teachers. Jim at high schools, Shirley with younger kids. Eventually, Jim landed as a music teacher at Lockerby high school in Sudbury. They lived not far from Lake Ramsay. And, as often happened in the 50’s and 60’s, their own kids soon arrived. Catherine, then Karen.

“In Sudbury, Jim and Shirley joined the Canadian Power Squadron, which as you may know is an organization that instructs boaters in safety and navigation, where they befriended Wyn and Bonnie Rhydwen.”

“I’ve been able to find much less about the Rhydwens,” said Mr. Strobel. “I found their marriage certificate from wartime Halifax. They wed in June 1943. Bonnie Carmichael was a local Haligonian girl, 21. Believe it or not she was classified as a ‘spinster’ on the marriage certificate. I don’t think that would happen today. Wynn was 28, an engineering officer in the Navy, eventually making lieutenant. He won a heroism medial in 1947 for saving a swimmer in the Atlantic off Nova Scotia, a bit of irony, given his fate.”

Wyn and Bonnie had a son, Brian. “After the war, Wyn joined Canadian Press and also worked for the old Halifax Mail and in public relations with the fisheries ministry. Before enlisting in the Navy, he had been a cub reporter for the Globe and Mail in Toronto, in Toronto, where his dad, Caradog Rhydwen, had been suburban editor and also the author of the definitive history book about Scarborough. Eventually, he moved his little family back to Toronto from Halifax.”

“In November 1963, son Brian, 19, was walking home in Scarborough along Old Kingston road, near my old neighbourhood, when he was struck and killed by a drunk driver, an off-duty postman,” said Mr. Strobel. “You could say it was a prelude to the even greater tragedy that lay just a few months ahead. Perhaps to escape their grief, the Rhydwens moved to Sudbury in 1964, Wyn as financial editor of the Sudbury Star and Bonnie as a cashier at the newspaper. They joined forces with their new friends the Huffmans to buy a boat, the Rhu.”

“So, now that you know the main characters in this Shakespearean tragedy, let’s turn to what happened to them, back in August 1965. They Huffmans had spent a week or so cruising up the east coast of Georgian Bay in their new boat from Midland to Pointe au Baril to Killarney. It was the Rhu’s first full trip as the Rhu, other than a couple of weekend outings earlier that summer. The weather was perfect. The Rhu left Beaverstone Bay east of Killarney on August 21 to pick up the Rhydwens in Little Current for a weekend of cruising the North Channel.”

“With their two families now on board, the cabin cruiser departed Little Current for Gore Bay. A beautiful, calm late summer afternoon. As they rounded Maple Point at the west side of Mudge Bay around 6 pm, they were headed directly into the blinding sun. Of the four adults, Bonnie had by far the least boating experience. But she was at the wheel. There was a reason for that. The others regularly got her to steer to keep her occupied. They were trying to pull her out of the dark and angry place she had been in since her son was killed by that drunk driver. So, it was Bonnie who piloted the boat around Maple Point. Jim and Wyn had done the chart work and they knew about Middle Bank. They spent a lot of time peering through binoculars for the shoals’ red marker and finally spotted it, but it wasn’t where it was supposed to be, apparently torn free by an earlier storm.”

Mr. Strobel showed pictures where the incident occurred. “Jim Huffman told me the Rhu hit Middle Bank like a flat skipping stone, then lurched to a stop. Wyn went below to check damage. Jim climbed out and pushed with Bonnie still at the wheel and they actually managed to move the boat a couple of times, but Middle Bank is an acre or more and they kept grounding out. The last time, the inboard engine tore loose from the stern. So, they were stuck. It was a beautiful night. They discussed whether one of them should swim to shore for help, but instead they waited out the night and to hail a passing boat in the morning.”

“Surely, there would be one. Even in 1965, you’d expect boats on a Sunday in August. So, they bedded down, Catherine and Karen in their bunks with the little hand-drawn name tags. The next morning, there were no boats, just a furious storm with driving rain and a big west wind that roared steadily at around 40 km/h and gusted to near 60.”

“The held on all that Sunday, rocked by two-to three-metre breakers pounding off the reef like geysers. The water broke the windshield and reached the stove, then the little girls’ bunks, so about 5 pm the two families decided to abandon ship. By the, the rain had stopped, but the wind and waves were ferocious. And another night, a much worse night than the first, loomed.”

Mr. Strobel explained, “They did not thin the Rhu would survive it. So, they strung rope through their lifejackets and stepped off the battered cruiser. They hoped to make it to what is now my shore. But Jim told me he knew they were doomed as soon as they entered the water. ‘It was very clear what was going to happen,’ he told me. Karen drowned within an hour without a sound, in her mother’s arms. The waves were just too big. Jim told me, ‘She was so young and so small, and she couldn’t resist it at all.’ Big sister Catherine died in her dad’s arms in the second hour. At age four, going on five, she was more aware of what was happening, Jim told me. When I asked him what he meant, he said, ‘I really don’t know what to tell you about that.’ With both daughters gone, Shirley was overcome with grief, struggling against the rope holding the living and the dead all together, screaming in the wind, ‘they were too good to be true, they were too good to be true,” Jim told me.

Wyn was in trouble, too. He had cramped up almost as soon as they entered the water. Jim told me he thought later that Wyn might have had a heart attack. ‘I asked him you okay’ and he just shook his head.’

“So, there you have it. As night fell, Bonnie clung to Wyn. Jim held the distraught Shirley. They drifted across the mouth of Mudge Bay. Wyn died next. Later, Bonnie would tell their newspaper, the Star, ‘He couldn’t talk. He sensed he was going. He held me close. I tied him closer to me, clung hard to his hand and talked to him, held his head, and said all the things that were in my heart.

Then Shirley died. ‘There’s not much I can tell you about that, either,’ Jim told me. Now, there were two left of the six, still roped to the bodies of their loved ones. It was a cool night, with air temperature at the Gore Bay weather station around 12 degrees, much cooler in the middle of the Channel of course, and the water was still choppy, but mercifully, the winds died down and the sky completely cleared.”

Bonnie and Jim could see the Kagawong lighthouse and the twinkling lights of town, but they might as well have been on another planet, said Mr. Strobel. “Sometime in the night, Jim’s feet dragged on the bottom, probably near one of the reefs and islands south of Clapperton. Possibly Little Island, which is east of the Dodge Lodge beach. Jim told Bonnie that he thought maybe their struggles were nearly over, but the current dragged them off. ‘We kind of gave up after that,’ Jim told me. But for the rest of the night they called out to each other, again and again, ‘You okay?’”

“Dawn was beautiful,” said Mr. Strobel. “Crystal clear, a breath of wet wind, the air temperature 16 degrees and climbing. A beautiful Monday. And they could see an island close by. Gooseberry Island on the east side of Mudge Bay. So, they decided to turn loose the four bodies, and you can imagine that decision and that moment, and make for the island. It took forever to untie the knots, their hands were so numb. Jim said he and Bonnie rolled ashore like logs, around 9 am. But fate was not done with them yet. Gooseberry Island was infested with horseflies so bad the two exhausted survivors had to cover themselves with brush. After awhile, they saw a small boat approaching. Two berry pickers from West Bay, now M’Chigeeng, took them to nearby Hideaway Lodge. The Sudbury Star sent a plane to pick them up and take them to hospital.”

Karen’s body washed up on the rocky shore near Honora the next day. A police boat was en route to pick her up when it came across the three others still roped together in Honora Bay. Finally, after two horrendous days, one ordeal was over. Other ordeals of a different kind, even worse in their way, were just beginning.

There was an inquest in Gore Bay that fall, and a coroner’s jury recommended installing improved markers at the Middle Bank (which was carried out). There was testimony about the life jackets, which bore the department of transportation stamp of approval, but had been useless in keeping the little girls’ heads above water.

“The mahogany carcass of the Rhu hunkered on Middle Bank for a week, until another storm blew it to the Manitoulin shore,” said Mr. Strobel. “Which of course, raises a heart-breaking question. So, the Rhu stayed on the shoal for a week. It didn’t completely break up as they’d feared it would. If they had hung on, might they have all survived? Easy to ask in hindsight, of course. It’s just one of many ‘what ifs’ to the wreck of the Rhu. What if they had flares? What if they had a dinghy? What if the Rhu had been a slightly earlier model of the Chris-Craft Cruiser Deluxe, when the draft was two inches less? Would that have made a difference on Middle Bank? What if Bonnie hadn’t been at the wheel? Would Jim or Wyn, who were boating instructors, have faired better? Pauline told me her sister had vivid premonitions of the fate awaiting her family and the Rhu. What if she had heeded them? Who knows?

“The Rhu rotted on that beach for two years. Then the Anglican Church was looking around for a new pulpit and somebody remembered the wreck. Locals like Aus Hunt and his boys and Harry Tracy salvaged the remains of the Rhu and the bow is the pulpit in the church to this day, with a little plaque honouring Shirley and her girls, and Wyn.”

“The guilt lasted a lifetime,” said Mr. Strobel. “Jim Huffman, a man who lost his whole family told me, ‘it was my job to protect them. I didn’t do that. I don’t forgive my guilt. Why even take a boat out there when you know it can be dangerous? Why didn’t I do this or do that? They’re not questions I can answer. There are no answers.’

Jim lost touch with Bonnie soon after the tragedy and I know very little about what become of her, said Mr. Strobel. Jim thought she’d moved to the UK. I’ve checked the cemetery in Toronto where Wyn and their son Brian are buried. There’s a place there for Bonnie, but it’s unclaimed. If she’s alive, she would be 103, but she just seems to have disappeared,” said Mr. Strobel.

He explained, “After the Rhu, Jim was also in a very dark place, as you can imagine. He took a year off teaching. He thought of suicide. He had a newfound loathing of seagulls. To us they are just birds. To Jim, they were like horrors in a Hitchcock movie. Why? Because seagulls are scavengers and he and Bonnie had to fight them off as they drifted, roped to their dead loved ones, in the Channel.”

“Jim credits a Sudbury church minister with backing him off the brink,” said Mr. Strobel. And he rebuilt his life. With his second family, he had a cottage and a boat. His new wife told me Jim didn’t like deep water, but he didn’t avoid it either. And whatever his imagined debt of guilt, he paid it off. Once a high school music teacher, he became a renowned and ground breaking guidance counsellor, leader of their provincial organization, he trained other teachers in suicide intervention and introduced crisis support teams. He won many awards for these things. And he volunteered for a group called Bereaved Families of Ontario. One of the many people he counselled there, a man who also had lost his children, gave him a carved wooden bird, it’s wings spread for takeoff. It bore an inscription as if written by the spirts of the man’s dead kids. “Thank you for helping our dad,” it read.

“Which goes to show you something, I guess. As impossible as it seems, there is consolation, real and important consolation in this story,” said Mr. Strobel. “The sheer tragedy of the Rhu eventually evolved into a story of recovery and redemption, if not triumph, at least for Jim Huffman. Thank goodness for that.”