MANITOULIN—Extreme cold temperatures in January caused a large jump in ice cover across the Great Lakes, going from below average to greater than normal ice concentrations. Warm temperatures earlier this month saw a return to average ice cover for the season. Lake ice loss in the northern hemisphere has been declining in general, largely due to climate change which also makes ice cover forecasting a little more challenging.

Climate change has made things rather difficult in the last 10 years alone, said Brad Drummond, a senior forecaster with the Canadian Ice Service (CIS). “In just a short three-year span from 2012 to 2014, we saw both the lowest ever ice coverage on the Great Lakes in 2012 through the highest ever recorded in 2014,” he said.

More frequent weather extremes in general are corresponding with trends in Great Lakes ice coverage. “There’s more rapid fluctuations with low ice years and high ice years but on the whole, we’re seeing less ice than we had previously, say in the 1980s and 1990s,” Mr. Drummond explained. “We’re seeing shorter seasons as well.”

Last year was a good example of this, with very low ice conditions through mid-January and then above-average ice conditions through the beginning of February. This then dropped off very quickly again. “The peaks are rather short for ice coverage on the Great Lakes as well,” he continued. “We’ve definitely noticed that the ice peak has come earlier in the season than it previously was, and the ice seasons are just generally shorter, by about a week earlier on either side of the ice season.”

Mr. Drummond and others at CIS have noticed that change, of ice forming earlier and breaking up earlier, for the past several years. Since the winters are generally warmer than they were previously, that means the ice hasn’t been getting as thick as it typically did either, meaning it’s easier to break up and melt out at the end of the season.

It’s not just happening here. A 2021 international study by limnologists (people who study lakes), ecologists and data information scientists at the Global Lake Ecological Observatory Network (GLEON) took a look at the long record of ice cover phenology.

“Phenology is a study of when things are changing in terms of time,” explained David Richardson, a co-lead of the study, along with Sapna Sharma of the Faculty of Science at York University in Toronto and Iestyn Woolway of the European Space Agency Climate Office in the United Kingdom. Professor Richardson is based at SUNY, New Paltz, in New York.

Think about timing in terms of the migration of birds, or when leaves come out on trees, or when specific plants produce fruit. “Ice is a really important thing on freshwater lakes because there are a lot of things that revolve around it,” Professor Richardson said.

The study looked at approximately 60 lakes from around the world, from Russia, Japan, northern Europe, Scandinavian countries and many in the United States and Canada, including some Great Lakes. “They’re all northern hemisphere lakes but they all have 100-years-plus records of their ice coverage,” he noted.

The Great Lakes are interesting, Professor Richardson said, because they are some of the biggest lakes in the world. “A number of our records are for specific bays and specific locations as opposed to the centre of the lakes which is typically what we have recorded for many other smaller lakes.”

Lakes have been losing their ice cover for some time now. A study from the 1990s looked at some of the same lakes (as the 2021 study) and found that lakes were losing their ice cover as a result of climate change and warming in the atmosphere. “We updated that and found that the lakes are warming way faster and freezing later, thawing earlier and have less ice, more so in the past 25 years than any previous time in any of these century long data sets,” said Professor Richardson.

This most recent study did not look at what it means, that the lakes are losing their ice cover, “outside of us extrapolating it and speculating a bit,” he added. “Yes, lakes that have really not at all experienced ice-free seasons in the past are now starting to experience them more and more. Over the last 10 to 15 years, we’ve seen single lakes that have frozen every single year for the past 100 years have had multiple ice-free times, including the Great Lakes.”

This is happening especially in places where air temperatures hover around freezing, so it’s lakes in these areas that are transitioning. That includes the Great Lakes latitude and follows along the United States-Canada border and even further south in some places. “That line is moving further and further north as things warm more and more,” said Professor Richardson. “So, we are seeing more ice-free winters or not even necessarily ice-free, but we are seeing more lakes that are freezing and thawing and freezing and thawing.”

We are seeing atypical winters, where winters overall are getting warmer but we’re also seeing warm and cold spells every single winter where we see freeze and thaw events, he said. “That kind of indicates the transition to the ice-free winter.”

Why should we care about ice cover? The obvious reason is the ice becomes less safe. Things that draw people to lakes over the winter such as skiing, snowmobiling and ice fishing become less feasible. Less ice cover will affect the economy and tourism and recreation. Ice loss will affect cultural and possibly religious activities, and there are implications for ecosystems.

“Less ice during the winter means warmer lakes during the summer because you have earlier thaws. More heat is being absorbed by the water,” Professor Richardson said. “Ultimately, you end up with bigger algal blooms over the summer. You end up with loss of fish species that can’t handle the warmer temperatures. All of these things are interconnected. The ecology of the lake in the summer is connected with what’s going on in the winter.”

He thinks it’s “interesting and kind of scary” that we’re seeing more extreme events. “We’re seeing more extremely late freezes of the lakes; more extremely early thaws; more extremely short ice seasons where we have zero ice with very short ice winters, and these match a lot of the other extreme events that are going on.”

With climate change, these extreme events are becoming more and more common and will lead to a fundamental shift in the ecosystems that directly affect us locally. The professor thinks it’s important to track these changes and adds, “One of our goals as humans should be reducing our harm to these ecosystems by minimizing our greenhouse gas emissions and modifying our ways of life to best prevent some of these catastrophic changes that are already happening, let alone into the future.”

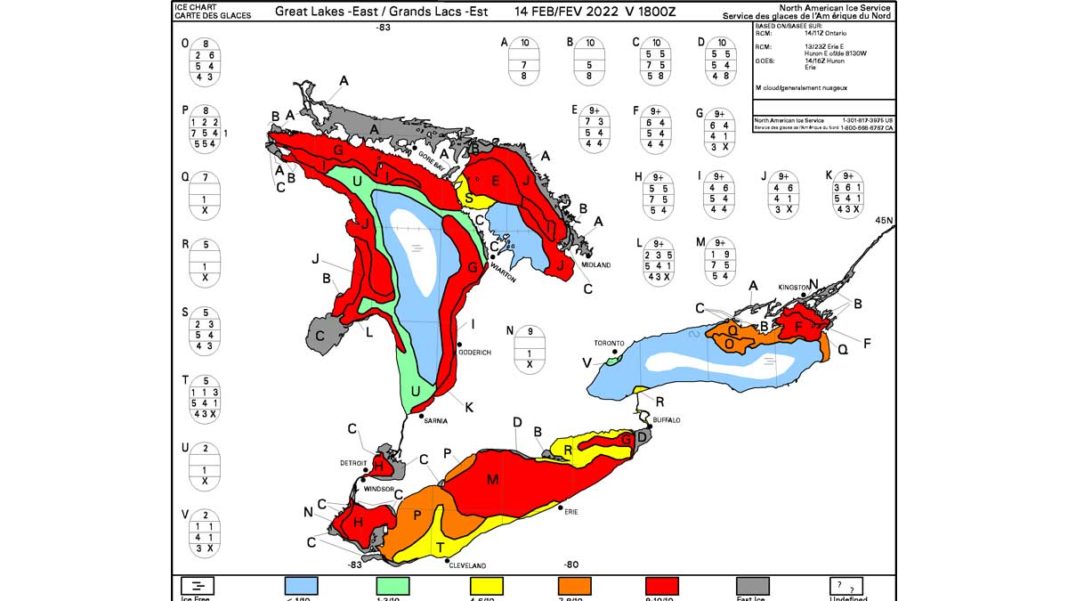

In the shorter term, Mr. Drummond is currently working on the next 30-day forecast for CIS. We are likely to see ice coverage in the great lakes grow slightly through the rest of February but that will start to decline rather quickly through March, he said.

February is kind of a volatile month for ice coverage, especially for the southern Great Lakes, as warmer low pressure systems approach. Warmer air temperatures at this time of year can make ice coverage fluctuate fairly quickly, especially for Lake Erie.

“Just this past week with these warm temperatures, we returned to right around average ice cover,” Mr. Drummond said. “We were significantly above last week. For the Great Lakes, the average is around 22 percent but we were up around 42 percent. That was mainly due to how much ice was on Lake Erie at the time.”

He expects ice cover to stay “around normal” for the next two weeks before things start to drop off.