M’CHIGEENG—According to the latest statistics, the danger of sexual assault will follow female children on into adulthood, while for most boys the likelihood of being sexually assaulted diminishes with age. Those were some of the sobering facts delivered to a Friday morning assembly of Manitoulin Secondary School students during a recent address by 2013 Governor General’s Award winner and former MSS student Julie Lalonde.

The stats are truly unsettling. “One in three women and one in six boys will experience sexual violence in their lifetime,” she said. “Young women under 25 show the highest rates of sexual assault. Women face that reality for the rest of their lives,” continued Ms. Lalonde, while in comparison, “the chances of a grown man being sexually assaulted are almost zip.”

“Who has marathoned through an all-nighter watching CSI or Law and Order episodes?” asked Ms. Lalonde. “Come on, hands up, no shame,” she quipped. “Watching on television, its always ‘stranger danger,’ right?”

The truth of sexual assault paints a far different picture than what is portrayed on television. “Between 80 percent and 95 percent of people are assaulted by someone they know,” she said. “The highest rates of sexual assault take place in the home or a college or university campus and the reported incidents are just a fraction of what is going down.”

These days, everybody and their neighbour has been talking about Jian Ghomeshi and/or Bill Cosby, she said. “A lot of this stuff happened 30 years ago. Why are we talking about it now? I like to think it is because we are moving from this to this,” she said, referencing a slide showing hands pointing down with a caption of “blaming the rape survivors” and another with hands pointing up captioned “supporting rape survivors.” The slide posed the question “which culture do you want to live in?”

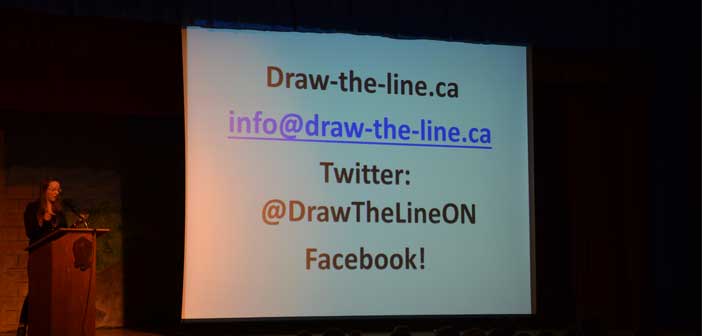

Ms. Lalonde is a veteran speaker whose public speaking skills far belie her youth. Her Governor General’s Award in Commemoration of the Persons Case was awarded for her “outstanding contribution to improving the quality of life for women in Canada.” Her citation says that she “has made a real difference in improving the lives of women and girls through her work to end sexual assault and sexual harassment.” A graduate student at Carleton University, where she studies the impact of poverty and isolation on elderly women, Ms. Lalonde co-chaired the Miss G Project for Equity in Education (Ottawa chapter), successfully lobbying for a new curriculum on gender equality for Ontario high schools and as a young professional, she developed and manages “Draw the Line,” the Province of Ontario’s anti-sexual violence public education campaign. She now resides in Ottawa.

Ms. Lalonde also has worked as project manager and as a volunteer with the Canadian Feminist Alliance for International Action (FAFIA, founded the first Canadian chapter of Hollaback!, an innovative new online tool for ending sexual harassment and, for the past several years, she has been an active volunteer with the Sexual Assault Support Centre of Ottawa. She hosts a weekly feminist radio program on an Ottawa-based community radio station CHUO, was shortlisted for the 2009 YWCA Women of Distinction Award and was the winner of the 2011 Femmy Award for strengthening women’s equality in the National Capital Region.

She quickly captured the attention of the MSS students in her audience as she first took them on an exploration of society’s and their own views on sexual violence, particularly focussing on the exploitation of young women on social media and the bystander effect.

The bystander effect, she explained, “occurs when the presence of others hinders an individual from intervening in an emergency situation.” It is the belief that inaction is an option because “someone else will do something” or “they did nothing, so why should I bother?”

The excuses we give ourselves are too often based in the “blame the victim culture,” with reactions such as “if she didn’t want to get assaulted, she shouldn’t have drank/dressed that way/hung out with him/gone to that party” or cop outs reactions such as “I didn’t think it was wrong,” “I didn’t want it to come back to me (a common refrain in the Ghomeshi/Cosby accusations),” or “I knew it was wrong, but I didn’t know what to do.”

It was largely that last excuse that Draw the Line and Ms. Lalonde’s address put in the crosshairs.

She used the real-life example of downloading a song by your favourite singer, who you learned has assaulted his girlfriend. “Do you download his latest song (and support him)?” she asked the students.

By doing so, you are participating in the culture of sexual violence. “Your money, your Facebook likes and/or vote is supporting them,” she said. “You are saying, ‘I agree with this!’”

Instead of downloading that song, Ms. Lalonde advised the students on a number of strategies. “Talk about it,” she said. Let others know where you stand; don’t support a perpetrator with money, Facebook likes or a vote, said Ms. Lalonde. “Think twice about the choices you make every day. Can you take a stand, make a statement and draw the line?”

The challenge before the youth of today is clear, asserts Ms. Lalonde. Youth can make a difference by refusing to buy into the outdated culture that supports sexual predators and embracing a culture that supports the survivors.

Ms. Lalonde offered the topic of sexting and the sharing of naked photographs, posing the question “a friend sends you a naked picture of a girl he knows, is it a big deal to share it with others?” It is.

Ms. Lalonde had posed the question of consent at the beginning of her talk and the answer was quick and clear. These days “every Grade 5 knows the answer to that question,” she said. The definition is clear in law, “consent is voluntary, sober, enthusiastic and never assumed.”

If there is no clear, explicit consent on the part of an adult in the photograph, if a third party sent it, you cannot assume consent on the part of the person in the photograph. It is simple and it is clear, sharing that photograph is a sexual assault on the person in the photo—full stop.

If the photograph is of a minor, then it is classified as child pornography, even if the person in the picture consented to it being taken and shared—full stop.

Moreover, under new laws coming out soon, should you use a phone or computer or tablet or any other electronic equipment registered to your parents to send or store that photograph, your parents are guilty of possessing and/or distributing child pornography. “If your parent crosses a border with a laptop containing that picture, they are now facing international trafficking in child pornography charges,” she said. “Do you want to put that on them?”

The stratagems for dealing with a picture you know is wrong are fairly straightforward. “Don’t open it,” is the simplest. “Don’t share it,” is also simple. “Literally do nothing and you are better than anybody else,” said Ms. Lalonde. The prurient interest that drives us to condemn an action and then rush off to Google the photograph must be resisted.

But Ms. Lalonde exhorted her audience to go further, however.

“You have to report it,” she said. “The second you get it, report it to someone in authority but not the whole world. If you sit on it, the police have to assume that you are okay with it.”

Ms. Lalonde said that she was “okay” with people choosing to act simply “to save your own skin.”

But she also told the students to “have a backbone” and to tell the person who is in the photograph. Not knowing that the photograph is out there robs the person who is being assaulted of any opportunity to limit the damage or to respond. “For Amanda Todd, the pictures were going around for weeks without her knowing about it,” she said. Everyone she knew was complicit. If someone had the courage to tell her what was happening, her tragic death might have been averted. “But nobody, nobody, had her back.” That is a devastating realization for anyone, but for a vulnerable teen it proved unbearable.

Ms. Lalonde asked her audience to commit to doing three things to help make our culture a better world: “Call out the behaviour, support the person and speak out,” she said.

Student Skyler Danville was among a group of students, all young women, who were gathered around Ms. Lalonde following her presentation. Her verdict? “It was awesome,” she said. “People need to know how wrong it is and how to stop it.”

Alexis French agreed, pointing out that the subject matter was far from theoretical. “It is definitely an issue in our school,” she said, noting that silence on the subject may leave parents with a false sense of security.

“We need more presentations like this,” agreed student Alisha Ledain. “A lot of people don’t talk about it.”

Manitoulin and North Shore Victim Services Executive Director Ashley Jewell said that she was excited about how the presentation was inspiring students to talk about the issue and to learn about the importance of supporting the victim and learning what they can do about the issue.

Manitoulin Family Resources Executive Director Marnie Hall Brown was also in the audience watching the students interact with the speaker. “I think the presentation was fantastic,” she said. “Thanks to funding through the Ontario Women’s Directorate we were able to coordinate these talks at three high schools (MSS, Wikwemikong High School and Espanola High School) in our area and that too is fantastic.”