PROVIDENCE BAY—Blair Sullivan had signed up to join the Royal Canadian Air Force during the Christmas holidays of 1942, but before June 1, 1943 when he was to travel to the recruiting station in Windsor, a draft notice appeared in the mail at his parent’s Madison County, Indiana home informing him he had been drafted by the US Army and was to report for basic training in a field artillery battalion at Camp Roberts, California.

“Needless to say I found myself in the US Army doing basic training on the very day I was supposed to report to the RCAF,” he laughed when interviewed about his wartime experiences by The Expositor.

Mr. Sullivan had wound up in the US because his father, an accomplished mechanic, had been offered a job with the manufacturing plant that General Motors had to repatriate from Saskatchewan to Indiana after the start of the war due to the US Neutrality Act. When the plant, loaded onto numerous flatbed cars was hauled back across the border, Mr. Sullivan’s father and his family followed the job. At that time, early in the war, the United States was a neutral country in the fray, unlike Canada which had declared war on Germany a week after the United Kingdom made the same move in August 1939. By the time young Blair Sullivan had moved with his family to Wisconsin, the Japanese had attacked the US ships in the Hawaiian port of Pearl Harbor and the US had joined the war against Germany and Japan.

At the end of basic training at Camp Roberts, Mr. (now Private) Sullivan was told to report to an office where he, along with six other high scorers selected from amongst the 500-man battalion were interviewed by a Lieutenant Colonel. “He gave us three options,” recalled Mr. Sullivan. “Firstly, we could remain with the unit and ship out to some place in the Pacific, secondly transfer to Fort Still, Oklahoma and go through officer training school to graduate as a 2nd Lieutenant in the field artillery or, thirdly, transfer to Stanford University and enter an army specialized training program as a pre-engineering student.”

The decision didn’t take long. “I told him my decision, saluted and left to register for the transfer to Stanford,” he laughed.

His battalion left for the Pacific Theatre shortly after, where they took part in the battle for Bougainville. He received a letter from a buddy who told him how the battalion was “badly mauled by the Japanese.”

“Some of the landing craft had gone aground offshore and were easy targets for the Japanese guns on shore,” he said. The Japanese were eventually defeated at a heavy cost.

Mr. Sullivan enjoyed a much different life at Stanford “but it wasn’t to last for long,” he said ruefully. “In early September, our group was notified that changes were coming. We were to list our interest in transferring to another school. I listed Indiana University as my first choice (close to his family and the girlfriend Lillian who was later to become his wife of 65 years) and was really surprised that I was chosen to go there.”

He spent the next little while ensconced in an “academic grind,” but with the aid of some extra fuel rationing stamps and most weekends free, it wasn’t so very bad. But things were heating up in Europe and Mr. Sullivan soon found himself assigned to the survey and forward recon squad of the 516th field artillery battalion training for the field at the Camp Shelby range.

His squad leader was a so-called 90-day wonder, a 2nd Lt. Goodyear (yes, one of “the” Goodyears of tire fame) who was a recent graduate of Princeton who had been in the army all of 90 days before his arrival at Camp Shelby. Most of the rest of the officer contingent were graduates of officer training schools, but the battalion commander was a Lt. Col. Sol Bloodworth, a West Point graduate and regular army through and through.

The next few weeks were a blur of forced marches, rifle range work and hand-to-hand combat training. There was no mistaking it, their unit was headed into the thick of it. Training was no piece of cake. As recon scouts for the battalion’s 12 Long Tom artillery pieces, they found themselves wading through streams and bogs to set up sight lines. Mr. Sullivan’s exuberant leap across one stream not only landed him in the cold water, but he found himself face to face with the open mouth of a very angry and venomous water moccasin snake.

“With a great leap, and by thrashing about I escaped the snake and rushed from the scene,” he recalled. “My buddies, some several hundred yards away, were laughing their heads off.”

In early July, the 500 men of the 516th battalion embarked for the war in Europe aboard the four-stacked 49,000 ton Cunard liner Aquitania, a sister ship of the Titanic, along with 20,000 troops and 600 army nurses packed on its 12 decks.

The Aquitania was one of the fastest ships afloat, but it spent much of its time zigzagging to avoid German U-boats, safely arriving nine days later at the Firth of Clyde in total darkness.

As they travelled to their jump-off port aboard troop trains, children who had been evacuated from other parts of England to escape the blitz lined the streets with shouts of “gum chum.” Thanks to a ship-board briefing, the soldiers of the 516th had stocked up on sticks of gum for the occasion.

As they waited two months for their deployment, ensconced at their Broadstone golf course and country club mess hall (the nine-hole course made a great sighting range for artillery gun crews), it was not unusual to hear the drone of German aircraft or VI buzz bombs overhead. “They appeared to have little accuracy,” recalled Mr. Sullivan.

But eventually the men of the 516th battalion and its 12 155mm Long Tom guns found themselves aboard 33 LSTs (landing ship, tank) bound for the north shore of the River Seine and the French city of Rouen.

The next morning the battalion suffered its first casualty. “The bottom of our LST had some of our 155s chained to the hull,” he said. “Several of the gun crewmen were playing cards on blankets when a sudden lurch of the ship broke one of the chains.” A track broke free from one of the guns and severed the leg of one of the gun crew. Despite the medical officer’s best efforts, the injury proved fatal.

Once landed, the men of the 516th faced a disheartening first day as liberators. “As we entered a small village, we were angered to see some of the villagers spitting at us,” he recalled. “Had we come to overthrow the Germans or were these people satisfied with the German occupation? We never knew the answer.”

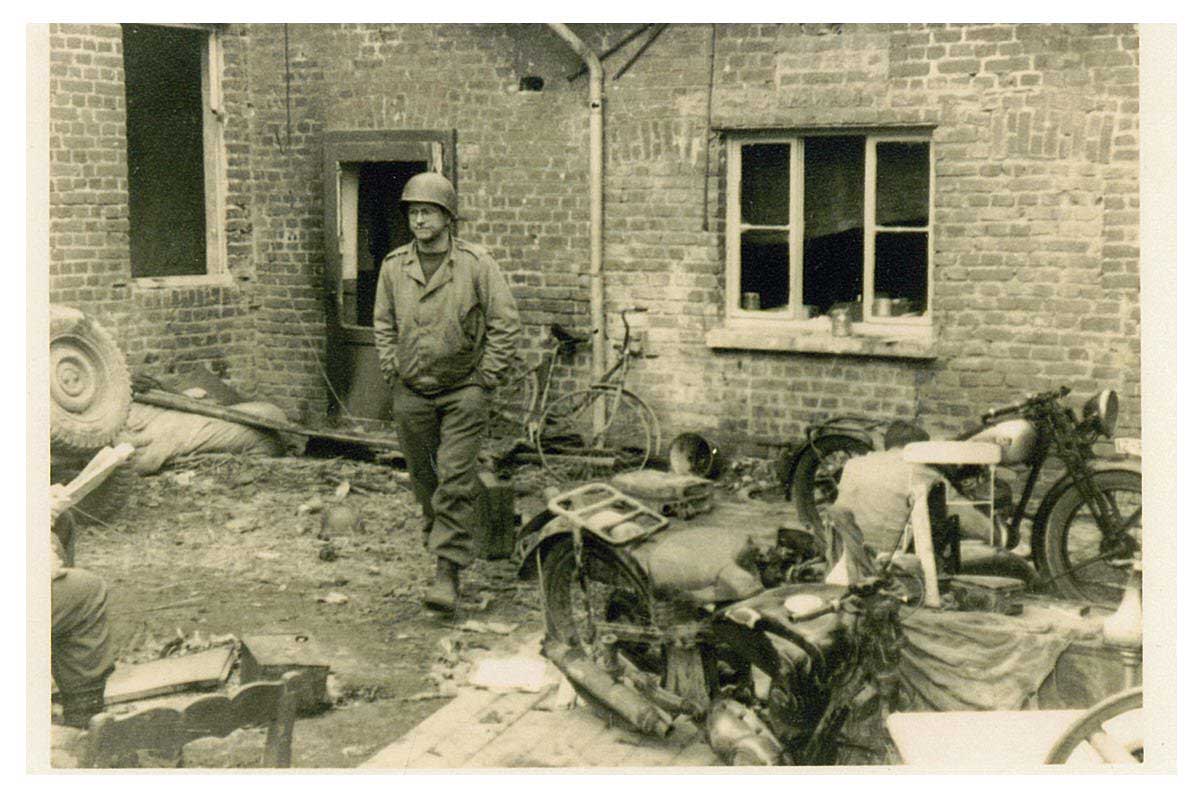

So began the steady march across Fortress Europe. “All along the roads, in towns and fields, we saw the ravages of war—many dead horses and destroyed vehicles,” he said. His unit was to see a lot of death in the coming months.

The 516th arrived just in time to greet the December 16 German counterattack known to history as The Battle of the Bulge. The battle lasted until December 25 and through that time buzz bombs, the dreaded German rockets, flew over the village of St. Thrond where they were emplaced. “Several landed near our location and caused the barn we were living in to shake,” he said. “We counted out blessings.”

The firing of the Long Toms was deafening, and Mr. Sullivan traces some of his current hearing trouble to those concussions.

Close calls were plentiful enough. As Christmas Day was being celebrated with a delightfully well-timed mail jeep delivery, complete with a Christmas cake from home that they placed on a truck hood, a Messerschmitt 109 (German fighter plane) put in an appearance, sending everyone scrambling for cover as its guns straffed the courtyard. Luckily, on that occasion the cake was the only casualty.

There were plenty of casualties on both sides as the battalion continued its drive into Germany.

“I recall one blond haired soldier (one of several German bodies lying frozen) just a few yards in the open to the north of our underground home,” he recalled. “It appeared that before he died he had taken from his pocket several pictures of his family and friends.”

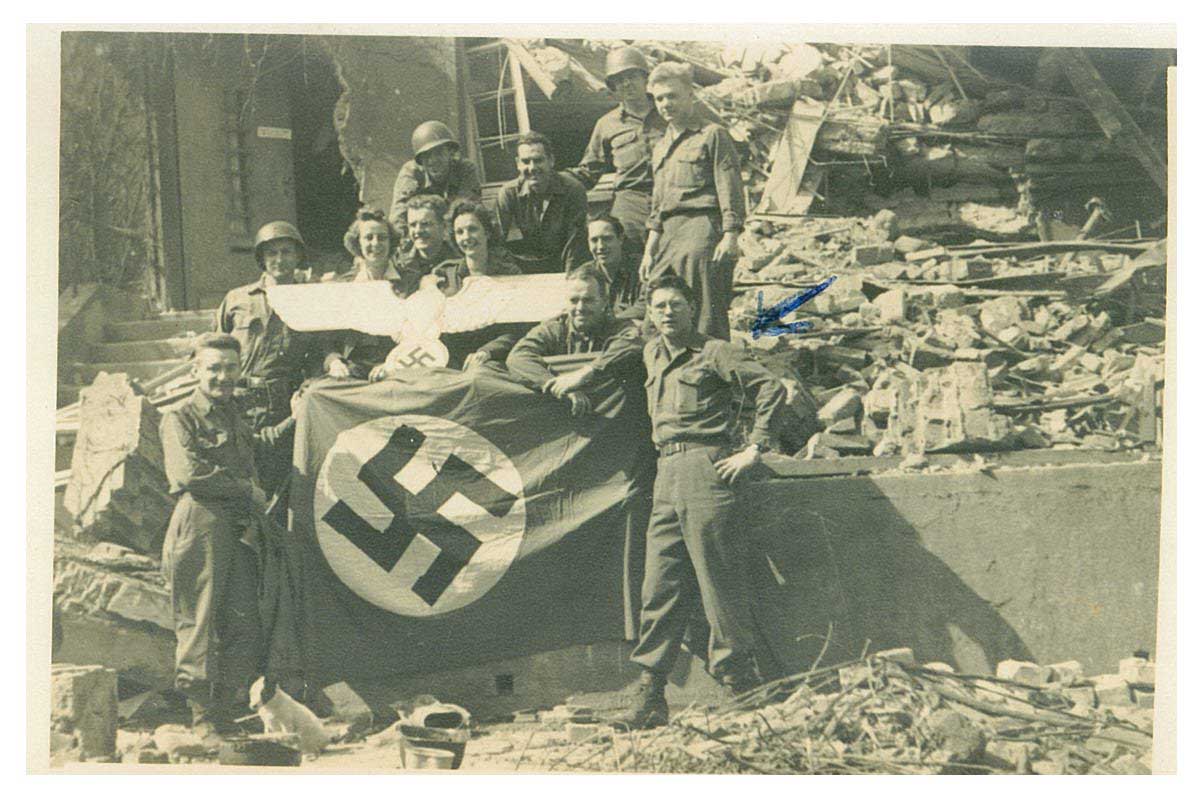

There were some moments of levity, including a few liberated bottles of wine, and following the cessation of hostilities, the battalion got to take in a performance by the legendary Jack Benny, including Ingrid Bergman, Larry Adler and Martha Tilton.

Mr. Sullivan was wounded in the hip when mortar rounds rained down on the destroyed barn where the recon squad was setting up their base. “I was headed down the stairs when it hit and I blacked out.”

His injured hip was worked on after the war, but it is still causing him a great deal of pain.

His return to America was fairly soon after the war. Men were repatriated on a point system that was based, in part, on the number of days they spent in combat. Mr. Sullivan had a large number of points amassed by the time the Germans had surrendered.

As they entered New York harbour, fireboats trained their water cannon on the ship in an exuberant (although somewhat less than appreciated) display of enthusiasm.

He underwent a rigorous series of medical exams before he was mustered out—more than the other members of his unit. “I asked what that was all about,” he recalled. The doctors informed him that, as the only Canadian in the 500-man 516th Battalion, they were making sure that he could not sue the USA in the future. As it turns out, Mr. Sullivan has few complaints about the way the US has compensated him for his service. “I get a pension every month for my hip and my ears,” he said.

Mr. Sullivan returned home to Indiana, where he married his wife Lillian (with whom he enjoyed 65 happy years of marriage). She was a public school health nurse and he spent the next 30 years as a high school biology teacher before returning to his family’s roots on Manitoulin Island.

You have to look hard, very hard, at the ribbons that festoon the breast of Mr. Sullivan’s Legion jacket, to see the two tiny bronze stars pinned to the European theatre campaign ribbon.

That’s not one, but two bronze stars recognizing his combat experience and heroism.

The bronze star is awarded to “any person who, while serving in any capacity in or with the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, or Coast Guard of the United States, after 6 December 1941, distinguishes, or has distinguished, herself or himself by heroic or meritorious achievement or service, not involving participation in aerial flight—(a) while engaged in an action against an enemy of the United States; (b) while engaged in military operations involving conflict with an opposing foreign force; or (c) while serving with friendly foreign forces engaged in an armed conflict against an opposing armed force in which the United States is not a belligerent party.”

Mr. Sullivan exemplifies those so-very ordinary extraordinary individuals who stepped up to serve their country (or countries in the case of many dual citizens) in its time of extreme peril, returning to home and hearth, bearing scars visible and invisible as reminders of those most terrible of days.

A more complete story of Mr. Sullivan’s life and times, along with greater detail of his military experiences can be found at the Central Manitoulin museum in Mindemoya.

Lest we forget.