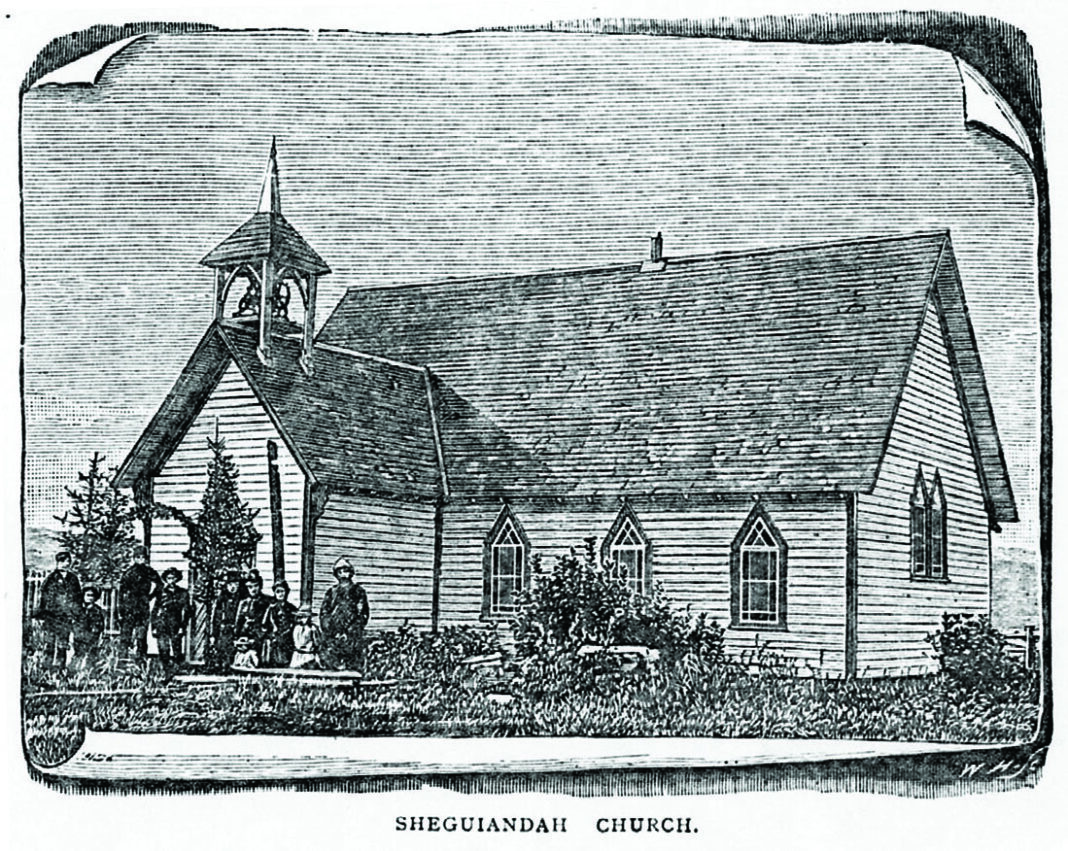

Fire destroyed an historic building in Sheguiandah First Nation on April 19, 2024. An online video of the smoke and flames on Manitoulin caught my attention. I recognized the building immediately as the former St. Andrew’s Anglican Church in Sheguiandah. I watched as the flames destroyed the eastern gable end and then devoured the belfry. The spectacle of the vibrant flames and billowing smoke was for me as heartbreaking as I assume it was for Parisians watching Notre Dame burning. Though unlike Notre Dame, which has inspired an entire country to rebuild it, St. Andrew’s will vanish.

Its disappearance does not simply mean the loss of another old building to fire or “progress.” It is the loss of a concrete symbol of the community’s history and of its Anishinaabe builders.

St. Andrew’s Church was entirely built by Anishinaabe hands 138 years ago. The builders’ descendants still live in Sheguiandah or Manitoulin.

As Expositor readers know, Manitoulin Island (Mnidoo Mnising or Odawa Mnising) has been the home of Anishinaabeg for thousands of years. At Sheguiandah this long residency is well documented. The Sheguiandah Archaeological Site illustrates the area’s ancient history.

The St. Andrew’s Church site commemorated more recent history, acknowledging Anishinaabe builders and restorers by name. Families like Manitowasing, Bahpewash, Muckadabin.

Sheguiandah Anishinaabeg wrote to the Anglican Bishop of Algoma in November 1884 and offered to supply the labour to build a new church to replace their 20-year-old log church/school building. Chief A. Manitowasing, James Bahpewash, Joseph Shebahgezhig, Wilson Kagesheyagha, Henry Muckadabin, Anthony Kageshagheyagha, William Bahpewash, John Gaikezheoongai “and others” signed the letter.

The Anishinaabe congregation’s determination to build the church themselves, with “no white architect,” inspired financial contributions for materials from all over the province. St. Andrew’s opened in July 1886. Services were conducted entirely in Anishnaabemowin, just as they had been since 1867 in its log predecessor.

This site also recalls the still controversial Treaty of 1862 and the relocation and merger of Anishinaabeg that resulted from the treaty. According to the terms of the treaty, Anishinaabeg were to be relocated from their homes on potential mill sites, harbours, parks and village sites to compact, mostly inland settlements. The Anishinaabeg of Sheguiandah and Manitowaning were particularly affected by the treaty’s terms due to the local Indian agent’s personal desire for land and his wish to appear successful professionally by resolving the resettlement of Anishinaabeg.

In 1867, while Canada was being created, the 70 Anishinaabe residents of Sheguiandah were joined by most of the Anishinaabe residents of Manitowaning. Sheguiandah grew almost overnight into a village of 129 persons or 29 families. In addition to the increase in population, the community had been moved south-west from its original location on the bay at the millstream, deemed a potential mill site, to inland lots south of Bass Lake.

A small log building was constructed in 1867 to serve the residents as a church and school. The little log structure was in use until replaced by St. Andrew’s in 1886.

I have a personal connection to Sheguiandah though I am not Anishinaabe. My great great grandfather Rev. Jabez Sims was posted to Manitowaning in 1864 as an Anglican missionary. He relocated to Sheguiandah in 1867 with his Anishinaabe neighbours. He witnessed their struggles as bands were merged, and lots were assigned based on the Indian agent’s desires rather than on Anishinaabe wishes. Sims’ children, including my great grandfather, attended school in the little log church.

The church served the community for about 100 years. In 1998 the late Clara Waindubence initiated a project to recognize the site’s history and to restore the building to house a community museum. Clara was inspired, she said, by her knowledge that the community’s grandfathers worked on the construction of the building with Rev. Frederick Frost. She believed it was a shame to neglect the little church that so many had helped to erect, and where she had been baptized and had watered the pine and cedar trees as a child.

The church was decommissioned and Clara and her amazing volunteers, especially contractor Lucie Robitaille, rejuvenated the building. It was reopened in July 2004 as the Sheguiandah First Nation Heritage Museum Church. The building still contained carvings by Simon Esquimaux, the wood stove from the 1867 log church, the original handcrafted pews, baptismal font and pulpit.

Sadly, Clara’s dream went up in smoke on April 19, 2024. I hope Clara and the history of Sheguiandah will be remembered.

by Shelley Pearen

Shelley Pearen is the author of ‘Four Voices the Great Manitoulin Island Treaty of 1862,’ and transcriber, translator, and editor of the recently published ‘Wikwemikong Diariums 1844-1873.’