John Fox tells about his own experience

OTTAWA—John Fox is one of the 16,000 First Nations children taken into care by the Children’s Aid Society between the 1960s and the late 1980s to be placed in foster homes as part of what has become known as the Sixties Scoop. On February 14 an Ontario judge is expected to hand down a decision in the Ontario Sixties Scoop class action case.

The class action lawsuit was put forward by Marcia Brown and Robert Commanda on behalf of themselves and as many as 16,000 other indigenous persons who were part of the scoop, charging that the loss of cultural identity caused significant suffering. The suit was stalled for a year after being certified by the Ontario Superior Court of Justice due to an appeal filed by the federal government.

According to data gleaned from Northern Affairs Canada statistics from 1996, as many as 16,810 treaty status children were adopted out to predominantly non-Native families across Canada, the United States and even Europe.

At around age 11, John and his sister were taken from their mother and placed in a Manitoulin foster home. According to Mr. Fox, his mother at the time was suffering from substance abuse issues. The following is Mr. Fox’s recollection of his experience in the Sixties Scoop and the child welfare system in the 70s and 80s. None of the allegations made by Mr. Fox in this story have been proven in court.

The foster placement proved to be the tail of a snake that would plummet him into a life of substance abuse, anger and pain.

“It was violent,” Mr. Fox alleged of his foster home experience. “I saw the father beat up the mother all the time. The father was a bully.”

Mr. Fox claims that his time in the foster home was essentially one of an indentured worker. “I was a yard worker for them, a child labourer, a farm labourer.”

As might be expected, Mr. Fox’s memories of his experience poisoned his relationship with the foster family. “They know my views on it,” he said. “It was not a good place to learn how to be a parent. My biological sister was placed in the same family.”

“I was very fluent in the language, the principal in the school in Wikwemikong used to take me to public speaking engagements. The principal (Sarah Peltier) wanted to tutor me and used to visit me at home.”

Mr. Fox may have been fluently bilingual when he left Wikwemikong, but he soon ran up against his foster father, who was hostile to him speaking Anishinabemowin. “He would get really angry and tell me to shut up,” he said.

Mr. Fox said his Island placement came to an abrupt end when “I got punched in the face.”

He was then transferred off-Island to a foster family in Azilda, his sister went to another family. “We got scrambled,” he said. “They sent her somewhere else, I don’t know where. We never really connected again.”

The Azilda foster home was another experience entirely. “It was a different culture again,” he said, adding a different traumatic experience for a 13 year-old. “They were French. I was sent to a French school, everything was very different to anything I had ever known.” The stress was palpable.

“I failed every subject in school that year,” he said, “even art.” His social worker sat him down for a conversation. “She had my report card there in front of her and she was raking me over the coals about it. Whenever I saw a social worker, it was only to badger me. It was never anything good.”

Mr. Fox only lasted in the new home about a year. “One of my foster parents slapped me,” he said. He had gotten into a conflict with one of the family’s biological children. He made his way south.

“I called the other half of my family in Toronto,” he said. Shortly after he moved to live with them. “CAS butted in again,” he recalled. “They said I was a ward.”

CAS paid the going rate for foster parents, but that was the extent of their involvement in his wellbeing, he said. “I never saw my social worker.”

The Toronto situation was far from ideal, however, and he eventually had to leave his stepmother’s home, again having been there for less than a year. “I slept on a couch and dressed in the bathroom,” he said. Soon he began drinking heavily. “I got out of CAS care when I was about 15,” he recalled. “I was basically out on the streets of Toronto.”

He was on his own.

“CAS said they wouldn’t do anything for me because I didn’t have a place,” he said. “What a place to be dumped off without any help. I didn’t know anything; how to get an apartment, how to apply for welfare, I didn’t know any of these things.”

Wandering the infamous streets of Toronto’s 1970s Cabbagetown, Mr. Fox learned the ins and outs of life on the streets. “I called it the Bronx,” he said. “I knew all the places, where all the alleyways were, all the safe places to sleep.”

A few years later he discovered the Silver Dollar, at the time a favourite hangout for Natives who found themselves adrift in the Big Smoke. Since then the hotel has been gentrified as a jazz club and a music venue of note, and now is being torn down to make way for student housing. But in those days, the Silver Dollar was pretty much a dive known for one thing.

“That is where I learned to power drink,” said Mr. Fox. “I learned to drink hard.” It was a place where he could fit right in. “Everybody else drank. I was molded for that. I was a prime candidate.” A fog descended for the next decade.

“I came to one day and went into treatment; I went for help,” he said. It was August of 1986 when his epiphany came with a jolt. “I had been arrested for assault with a weapon,” he said. He had plenty of brushes with the law before, mischief and minor assaults, but this time it was serious. “Before it had been small things, but this time I was in big trouble,” he said. Not only had he attacked someone, he had also “trashed the place.”

“They stood me up in front of the judge a few months later,” he recalled. “They judge said ‘I am going to let you go’.” That was 30 years ago.

Since then there has been a lot of challenges, but he has managed to keep his commitment to that judge. “I contribute everything to sobriety,” he said. “I went to a lot of self-help groups, did a lot of talking, drank lots of coffee.”

He became a social worker, working in Northern communities for the next 20 years. “I went with a purpose,” he said. “I wanted to learn more about my identity, to learn more about me.” He worked as a youth crisis councillor for the Nishnawbe Aski Nation, for Child and Family Services, in Thunder Bay as a clinical youth councillor in a solvent abuse treatment centre.

“Instead of destroying myself, I wanted to help turn others around,” he said.

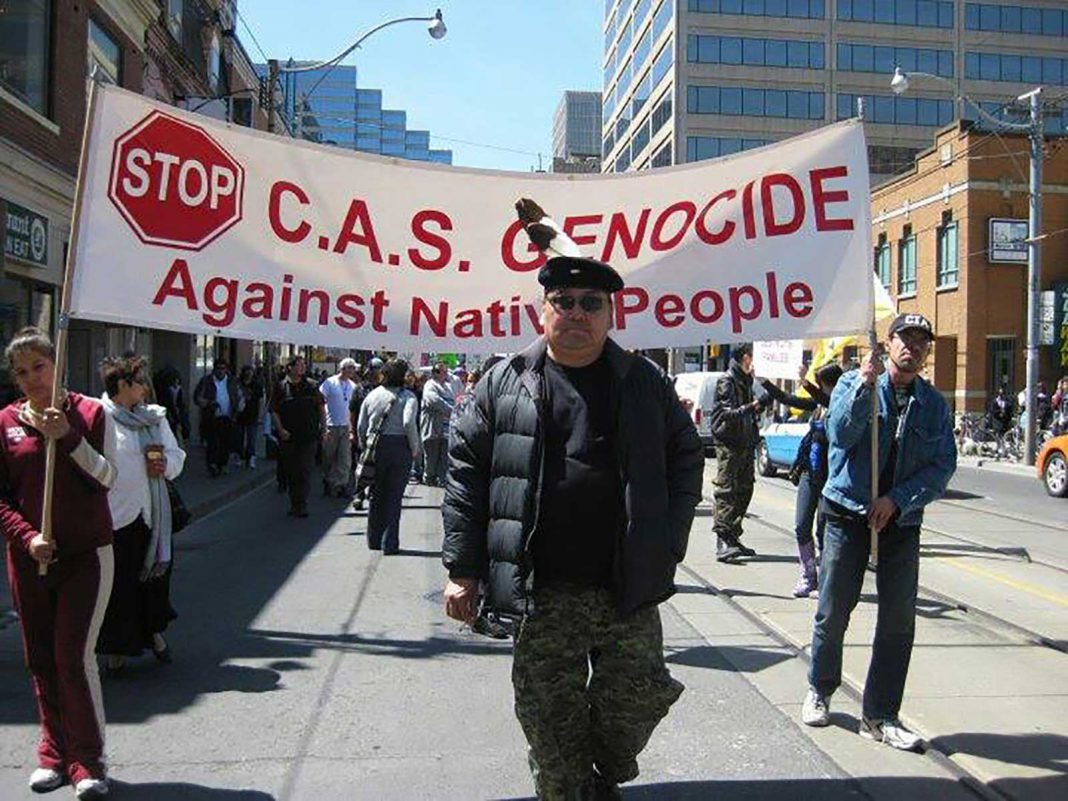

Mr. Fox started one of the first protest actions to bring awareness of the Sixties Scoop to the streets of Toronto.

“I felt strongly about it,” he said. “I didn’t want the next generation to go through what I went through. It really shaped who I am today.”

He credits his older sister, Donna Fox of Wikwemikong, with being a catalyst for his taking action. He found allies in the Council Fire organization in Toronto. “They help people in the downtown,” he said. They see a lot of the impact of the Sixties Scoop on the streets every day. “They helped me a lot,” he said. “They still help me a lot when I ask them.”

That first protest took place at Allen Gardens and there were about 250 people who took part.

“There was another one after that, and then another about five-six years ago that had about the same amount of people,” he said. “Allen Gardens has a special meaning for me and a lot of other people who found themselves on the streets. Sooner or later, everyone winds up there.”

Mr. Fox said that he was “cautiously optimistic” about the prospects for a resolution to the issues surrounding the Sixties Scoop following the announcement by Indigenous Affairs Minister Carolyn Bennett.

“I want four things to come of this,” he said. “One, I want the government to pay the full amount due to the survivors; two, I want to see the child welfare policies for First Nations to change, not just the legislation; three, I want a public apology to all the survivors; and four, I want to see a treatment regime for the survivors. There are still people hurting out there with no where to go. There should be something available.”

Mr. Fox’s family has gone through tremendous personal tragedy, his daughter Cheyenne Santana Marie Fox died tragically in Toronto when she was just 20 years-old. Ms. Fox fell from a 24th floor condo balcony in what police have since labelled a suicide, but her family members insist that hasty conclusion just doesn’t add up. The only witness to her alleged suicide was a client of Ms. Fox.

While Ms. Fox had a difficult relationship with authority, she is described by those who knew her best as “very compassionate, very caring, she didn’t judge anybody.”

Sadly, Ms. Fox is too often judged in death, as she was in life, and the insistence of the media in labelling her as a sex trade worker when her story comes to the fore continues to traumatize her family. One of the ongoing legacies of the intergenerational trauma that has assailed indigenous peoples through the centuries.

Ontario Regional Chief Isadore Day says that the federal government’s willingness to negotiate an end to the Sixties Scoop claim is a positive sign. However, they must acknowledge to the survivors and to Canada that they have a duty to protect the cultural identity of indigenous children.

INAC Minister Carolyn Bennett announced that the federal government wants to negotiate claims resulting from the Sixties Scoop.

Unfortunately, the federal government took the opportunity to request that the judge in the case temporarily withhold his ruling, an unprecedented move that brought about an immediate backlash and accusations of cynicism and manipulation on the part of the federal negotiators. The federal lawyers have since withdrawn that request.

“The practices of the child welfare system during the period associated with the Sixties Scoop are an ongoing source of great trauma for the indigenous community,” said Ontario Regional Chief Isadore Day. “The current despair felt in far too many of our communities is a direct result of having children taken from their families.”

The $1.3 billion class action lawsuit against the Attorney General of Canada was filed in 2009, on behalf of Marcia Brown, Chief of Beaver House First Nation.

The lawsuit alleges the federal government–with constitutional responsibility, principally through Indian and Northern Affairs Canada–committed “cultural genocide” by delegating child welfare services to Ontario. Approximately 16,000 at-risk indigenous children in Ontario suffered a devastating loss of identity when they were placed in non-indigenous homes from 1965 to 1984 under terms of a federal-provincial agreement.

“I want to lift up Chief Marcia Brown, the representative plaintiff in the lawsuit who led this charge with passion and determination on behalf of the thousands of survivors across the country. Minister Bennett stated that this is a ‘dark and painful chapter’ in Canadian history that needs to be resolved in order to advance healing and reconciliation. We know that much more healing needs to take place not only for the survivors, but for their children and grandchildren,” said Regional Chief Day.

“If this government is truly committed to reconciling its horrible historic treatment of indigenous peoples, then the upcoming federal budget must contain sufficient funding and resources to address a multitude of urgent needs,” he continued, “we need to address the ongoing suicide crisis with mental wellness programming. We need to break the cycle of poverty and despair with the necessary infrastructure for good homes and clean water. First Nation lives are not lines in a budget or dollar amounts in a lawsuit. All we need are the necessary resources to create happy and healthy communities in order to finally secure our rightful place in Canada.”