Part six of a health series

EDITOR’S NOTE: In the first five installments of this newspaper’s blastomycosis series, The Expositor delved into the human side of the fungal infection that took the life of one Manitoulin woman early this year. The infection is common among Manitoulin’s pet population and this sixth installment of the series will be exploring this more common host for the often deadly spore.

by Alicia McCutcheon

SHEGUIANDAH—Like part three of the series, the story that explored the life and untimely death of Gwen Young, a 47-year-old mother of two whose tragic passing led to The Expositor’s health series on blastomycosis, this article also centres around the village of Sheguiandah where many dogs, as well as two cats, have contracted the fungal infection. Many of these victims have died as a result of the infection.

By way of a recap, blastomycosis is a fungal spore found in rotted wood, vegetation and soil with low pH levels that, when breathed in (it can also be contracted through a cut in the skin, but this is more rare), can cause the spore to germinate within the body (typically the lungs) which can also spread to the central nervous system. It is often mistreated as pneumonia or even lung cancer as chest x-rays will show lesions on the lungs and patients will often present with a lingering cough, shortness of breath and, sometimes, weight loss.

Once diagnosed, treatment in humans can range from six to 12 months and is often given through pill form, a drug called itraconazole. In animals, this is the same treatment but the duration of the treatment is six months, sometimes longer

This winter, two of this reporter’s Sheguiandah neighbours had pets that succumbed to blasto—a cat and a puppy. In the case of the cat belonging to Chrissy Wade, animal activist, her mother Joanne explained that after a busy Christmas holiday and with members of the household away for a few days, she returned to find a very sick, lethargic cat (named Seneca) who was having trouble breathing. She was brought to the Island Animal Hospital and overseen by Dr. Johanne Paquet and, following a chest x-ray that showed her lungs were filled with yeast, Dr. Paquet was able to confirm her suspicions—the cat had blastomycosis. The cat’s health was so far gone that it was unlikely she would have survived but the Wades started their beloved pet on the itraconazole treatment with the hope that she would recover. Sadly, the cat died days later. An autopsy showed Seneca’s lungs were indeed filled with blasto lesions and the pet’s advanced infection had placed her beyond recovery. Within months of Seneca’s passing fellow neighbour Melanie Francis’ puppy also contracted the disease. The puppy also died soon after.

In June of this year, this reporter hired a local contractor to have a new septic system installed, with a giant hole created in the backyard to host the new tank and field bed. The thought of blasto, not far from the minds of many in Sheguiandah, crossed my mind while this construction was going on, especially when, two weeks later, I began to cough—a cough that persisted for over a month, worsening with each day, and which saw me at the hospital being taken seriously by a doctor about my concerns with blasto and sent off for a chest x-ray, a requisition for a sputum sample and later a blood sample. (The results show that I am in the clear.)

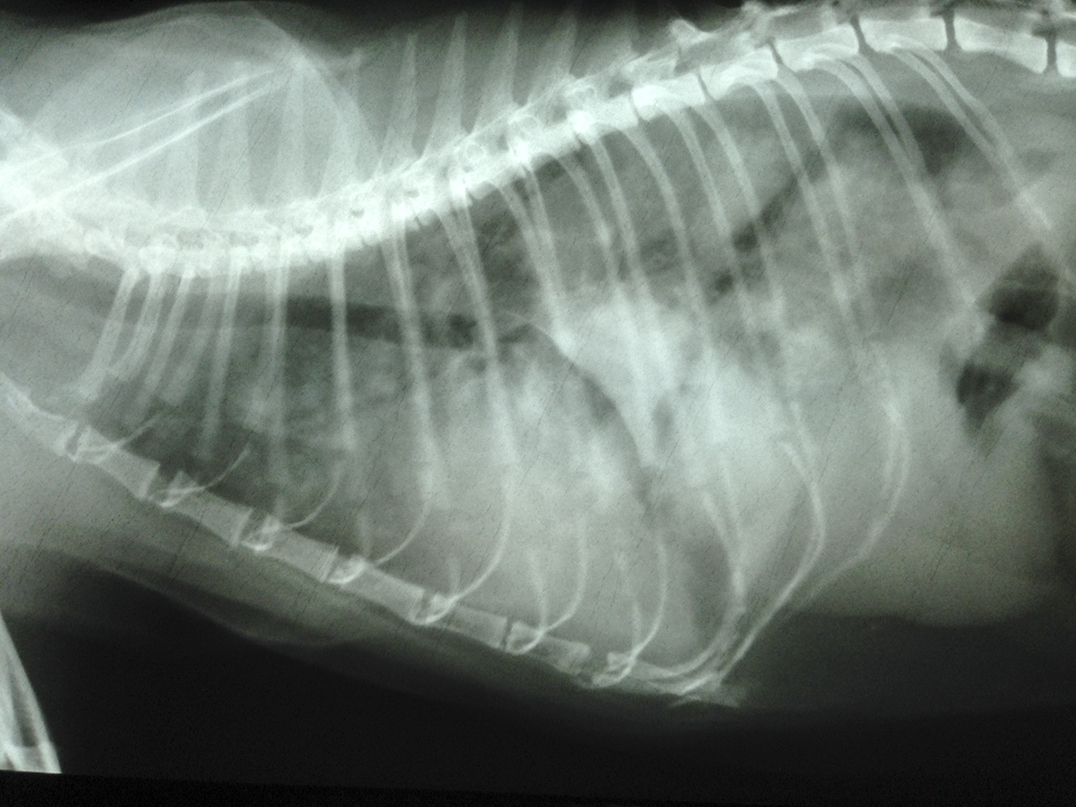

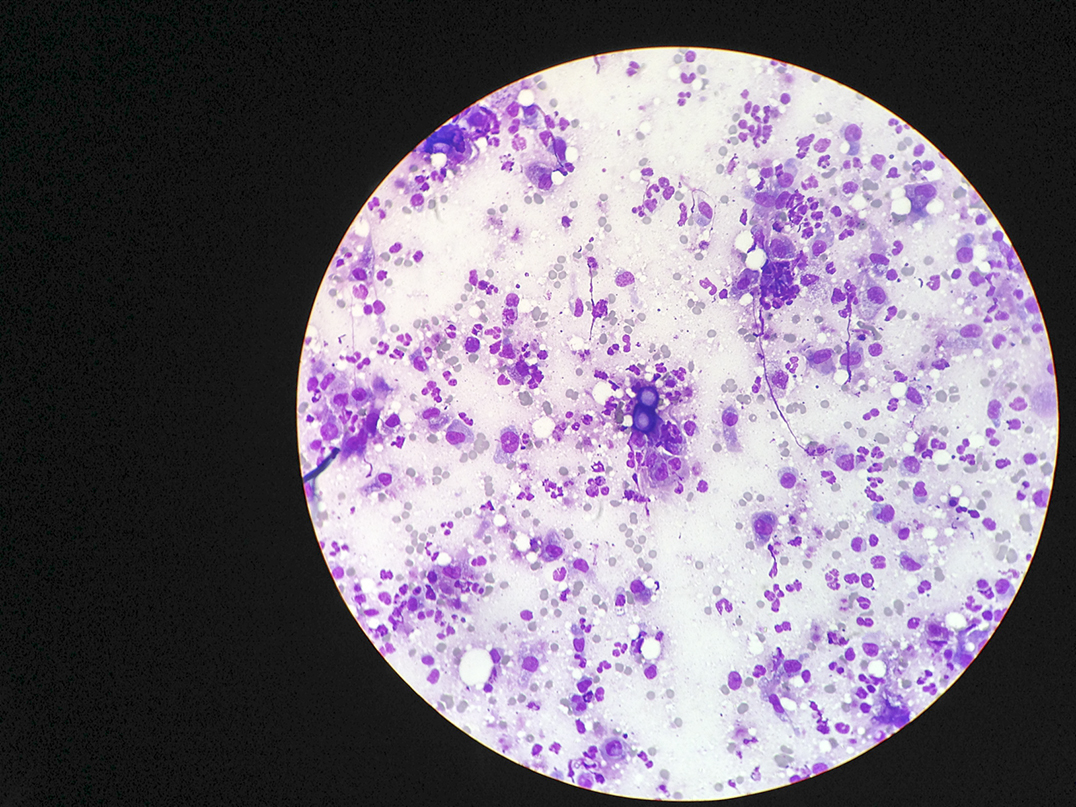

At this same time our cat Rudy, a big strapping fellow with a love of food, was becoming ill. He had already been treated for a wound on his front leg that required minor surgery and antibiotics, but it wasn’t getting better. Back for another trip to see his vet, Dr. Paquet, and the concern of blasto was mentioned. A chest x-ray showed spots on his lungs and a sample from a lesion found on his head also confirmed the news—the little purple figure eights of yeast showed Rudy had blasto, likely because of the backyard construction. He was immediately placed on itraconazole and given a 30 to 50 percent chance of survival. This was two weeks ago.

In Manitowaning, Cody MacKenzie was facing a similar dilemma with his faithful companion, a yellow lab-mix named Duke.

He explained that during the end of July heatwave Duke became noticeably ill, coughing up phlegm and showing no signs of energy and losing his appetite.

“It just came on so fast,” he said of Duke’s sickness.

Mr. MacKenzie took Duke to Scott Veterinary Services and was told he likely had blasto and that he had a 50/50 percent chance of surviving. The two were sent home with the itraconazole pills and a urine sample taken to be sent off to the only lab in North America to test for blasto in dogs, MiraVista Diagnostics in Indianapolis. (There is no urine analysis available for cats.) The urine sample proved to be contaminated and within three days the dog had gotten much worse—gagging, sleeping all the time and still not eating. The veterinarian ordered a new urine test which was again sent off to the lab. The day Mr. MacKenzie received the results, confirming Duke indeed had blasto, the dog had gotten up in the morning, taken his pills and died 15 minutes later.

“He was treated for two weeks,” Mr. MacKenzie said.

The veterinarian had asked Mr. MacKenzie if he had been to Sheguiandah with his dog any time in the previous months. He responded that they had, in fact, been to Sheguiandah Bay and Duke had walked the shoreline.

It became obvious that the blasto had left Duke’s lungs and entered his central nervous system when the dog began to walk in circles, Mr. MacKenzie noted.

“I hope your cat pulls through, but Duke took a turn for the worse,” he said, expressing his concern for Rudy.

Mr. MacKenzie’s mother Susan MacKenzie added it was her hope that the many people of Manitoulin affected by blasto lobby the Sudbury and District Health Unit and Ministry of Health and Long Term Care for signage, notifying visitors that Manitoulin is a blasto hot zone.

On the other side of the Island, in Evansville, Julia Winder and John Turner were rebuilding their home after a tragic fire in January of 2014. The earth had been overturned from construction and the couple had been taking plenty of walks on the property last fall, watching the building process of their new home with their three-year-old golden doodle Gordonach.

courtesy of Island Animal Hospital

In January of this year, the once-spunky dog was becoming increasingly sluggish and less interested in life, even when it came to his favourite game, ‘Mr. Towel,’ Ms. Winder told The Expositor.

He had been in for testing, again with Dr. Paquet, but it wasn’t until a seizure in the middle of the night that sent him to the vet’s office the next day that blasto became top-of-mind. It was that same week that one of the blasto articles in this series had been published in the paper, Ms. Winder recalled. “Blasto was definitely in my consciousness,” she said.

After the diagnosis, Gordonach’s breathing, at its worst, was almost one breath per second, she explained. The dog’s chest x-ray revealed what looked like “a snowstorm” of yeast. Because of the seizure, the golden doodle was also placed on phenobarbital as well as the anti-fungal itraconazole.

“The blasto meds and the phenobarbital made him so down and out he could hardly walk,” Ms. Winder said. “There was a chance he would not survive.”

Over six months in, Gordonach is back to being the playful dog he once was—the couple still keeps a close watch on his breathing, though. He recently had a blood test which still showed blasto, meaning Gordonach must remain on his medication for another three months, at least, but the Evansville couple is confident he will eventually see a full recovery.

At Scott Veterinary Clinic, Dr. Dale Scott said he sees between 12 and 16 cases each year, but has only ever seen one cat and this is likely because they do not display the same kind of digging and chewing attributes as their canine friends, so Rudy, Seneca and a cat in Birch Island, which didn’t survive, are rarities.

Dr. Scott said a typical dog will present with coughing, high fever, no appetite and fast, shallow breathing, problems with the eyes and sometimes skin lesions. He then looks at the community the animal is from, its environment, whether it is an outdoor dog, etc., followed by clinical signs.

“We start the medication right away, regardless—we’ve seen dogs die within 36 hours (of presenting with symptoms),” Dr. Scott said.

As with humans, blastomycosis in animals can be difficult to diagnose. “If not treated, the survival rate is low,” Dr. Scott added. “And the treatment is expensive and people have to be committed.” (A big dog’s daily treatment can cost between $10 and $14 while Rudy’s is $2.50.)

Dr. Scott said he had one dog the week before and three in July, noting blasto’s dormant nature.

While itraconazole is key, it is also very hard on the animal, Dr. Paquet explained, noting that it can cause liver disease. It also makes the already sick animal sicker for the first few weeks of treatment. “If they can get over that two to three weeks, then they typically do well,” she said.

Spring and fall are the most typical times for an animal to inhale the spore when there is more prevalence of rotting wood and vegetation.

“It’s not easy to prevent, almost impossible to prevent,” Dr. Scott added, “and if you’re from the high risk areas it always needs to be of concern.” (The high risk areas for Manitoulin, as cited by both local veterinarians, are Sheguiandah, Birch Island, McGregor Bay and Wikwemikong.)

If your pet presents any of the following signs, it is important that you see your vet as soon as possible, specifically if you are a pet owner in any of these areas, or have visited them with your pet.

• coughing

• problems breathing

• anorexia

• fever

• lethargy

• lesions on the eyes or skin

Dr. Paquet explained that whenever a cat is sick, they do an excellent job of masking their symptoms and the same goes of blasto. This is why the few cats that are found to have blasto survive because by the time their owners realize their pets are sick, they are typically so far gone their condition becomes untreatable. In the other Ontario hot zone, Kenora, a veterinarian sees 90 cases a year, only two of which are cats.

It is very rare to contract blasto from a pet or for a pet to pass the fungal disease on to another pet.

“If you’re on Manitoulin, it’s something you need to know about,” Dr. Scott added, noting that The Expositor series did a good job of making people aware of its presence. “It’s an endemic situation, and early detection is key, but there’s no need for alarm.”

As for Rudy, he is on week two of his treatment, resting at home, and showing signs of improvement day by day, slowly but surely. Dr. Paquet said it is likely his love for food that has kept him going. Fingers crossed, Rudy will hopefully be Manitoulin’s first blastomycosis cat survivor.