LITTLE CURRENT—The artisan incubation centre (Northeast Town council chambers) in Little Current was filled to over-flowing for a presentation on blastomycosis hosted by The Manitoulin Expositor and the Northeast Town.

“We were very pleased by the turnout,” said presentation organizer Alicia McCutcheon. “Obviously blastomycosis is something that holds a great deal of interest for people on Manitoulin.”

Northeast Town Mayor Al MacNevin said that he was also pleased with the turnout. “There are a lot of people who were interested in learning more about blastomycosis,” he said. “I know that there were a lot more questions than there were answers for some people, but it did help to take the mystery out of a lot of questions in my mind.”

“For me it was also interesting to see how many people living in Sheguiandah whose dogs had been affected,” said the mayor. “I found the evening to be very informative personally. I had no idea that the quartzite in Sheguiandah would make the soil there acidic. When you consider how most of the Island is limestone, you wouldn’t think that there would be acidic conditions in the soil.”

Interest in the presentation actually extended far beyond Manitoulin’s shores, with calls coming in from as far away as Parry Sound just prior to the event. The June 8 meeting in Little Current marked the first live streaming event for The Expositor’s Facebook page, a learning process that saw half the meeting streamed sideways online, but with clear audio.

The meeting saw presentations from Sudbury and District Health Unit Environmental (SDHU) Health Division Manager Holly Browne (with supporting input from SDHU Manager Burgess Hawkins), local physician Dr. Stephen Cooper and local veterinarian Dr. Johanne Paquet, of the Island Animal Hospital in Mindemoya. Refreshments for the evening were supplied by The Expositor.

From a medical and human health perspective, the symptoms presented by blastomycosis provide a signal challenge when it comes to diagnosis as they largely mimic common respiratory ailments. Ms. Browne presented data that indicate an incidence rate in the general population of two in 100,000.

Ms. Browne explained that blastomycosis is an uncommon infection caused by the fungus blastomyces dermatidis, usually found in soil. The infection affects mainly the lungs and skin and although it has really only hit most people’s radar recently (particularly with two recent deaths attributed to the disease), it has actually been a known infection for many years.

The geographic region that blastomycosis is known to exist in is vast, stretching from the Mississippi River, through the Great Lakes, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, through Ontario and into Quebec.

Its symptoms include a cough, shortness of breath, sweating, fever, fatigue, malaise, unintentional weight loss, joint and muscular stiffness and pain, and can include a rash and skin lesions. As common as the symptoms may be, the infection itself is quite uncommon.

“It is uncommon when you look at the statistics,” said Ms. Browne. Less than 50 percent of those who have blastomycosis even present symptoms and another complicating factor is that the incubation period for the infection is relatively long, from three weeks to three months, ensuring that the onset of the symptoms can occur long after the initial exposure. “I don’t remember what I had for dinner three weeks ago,” admitted Ms. Browne. “I don’t know if I would think to tell a doctor” about a possible exposure.

The ideal conditions for contracting blastomycosis are by breathing in the spores from disturbed soil (such as working in the garden, digging a house foundation or a well), while less common is rubbing the fungus into broken skin. What you cannot do is to contract blastomycosis through person to person (or pet) contact.

The spores occur naturally, but little is known about the spores and their environment. It is thought to thrive best in moist, acidic soil that is high in organic matter—especially excrement, decaying vegetation and rotting wood. Both testing for the presence of the spores and treatment to decontaminate soil is problematic, with complications apparently thwarting all attempts to accomplish such to date.

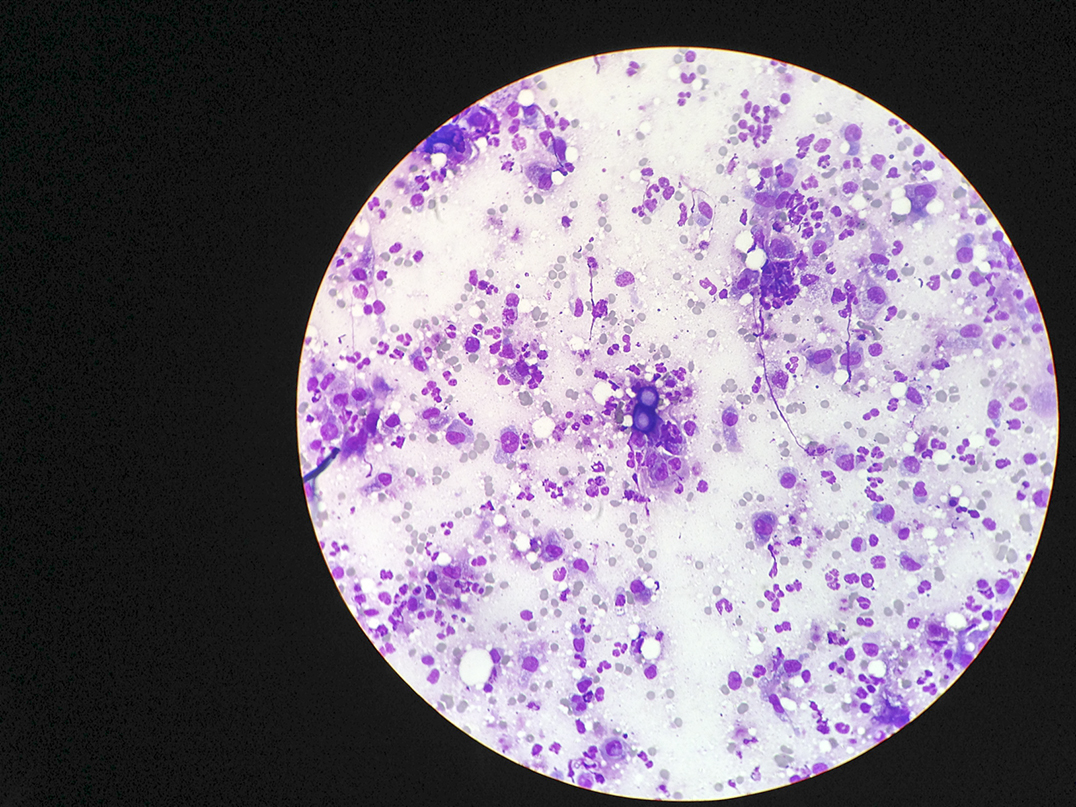

While the time between exposure and first symptoms ranges from three weeks to three-and-a-half months, it most often manifests between 30 and 45 days. Diagnosis is usually confirmed through sputum or tissue samples (which is a very invasive procedure that is not without the risk of complications).

Asked after the meeting whether the cost of testing was a factor in the frequency of testing, Dr. Cooper gave an emphatic “no!” in response. “Cost of a test is never a factor,” he asserted. “If a test needs to be done, it is done if the test is of clinical use.”

The long incubation period may well explain how the highest rates of incidence are in urban areas such as the Greater Toronto Area. With larger populations, the higher reported incidents from those centres make sense if one was to consider that people would not be aware of the symptoms until they had returned home from vacationing at the cottage or camp.

While Toronto is number one in reported cases, Sudbury ranks at number four.

Each of the health professionals emphasised that the key element in triggering the diagnostic tests for blastomycosis would be a prolonged persistence of the symptoms listed.

Protection from blastomyscosis focusses on being aware of the activities that might bring about exposure and taking relevant precautions. Exposure can occur when close to shorelines, hunting, trapping, camping, gardening with shovels, clearing weeds, chopping wood, working with rotting wood or digging holes.

“It is important to keep perspective,” cautioned Ms. Browne. “The risk of infection is low and medications do work.”

Mr. Hawkins noted that exposure to the spores would be more likely to occur through the hauling of wood to the woodpile than in the chopping of the wood. But advised that if you are going to be working with clearing rotted wood, stronger precautions may be warranted. Protective gear can include long sleeve shirts and long pants, work gloves, proper footwear and a disposable filter dust mask. “Not one of those dental masks,” cautioned Mr. Burgess, “one with a disposable filter.”

Blastomycosis is not a “reportable” infection, complicating the data picture, but the reasons that it is not in that category have a solid basis. First, reportable infections tend to be those that can be transmitted from person to person and have the potential to grow significantly in numbers, secondly, the reason for being “reportable” is to locate the source of the infection, such as in the case of a listeria or salmonella outbreak. In the case of blastomycosis, the source of the infection and its locale are fairly well delineated.

The incidence of blastomycosis amongst pets, particularly dogs, is less uncommon than among humans. “You see it a lot more in dogs,” said Dr. Paquet. Diagnosis of the condition amongst dogs may well be aided by the fact that the infection is usually very far along in the pet before the owner brings them in, she noted.

The infection leaves a distinct pattern on an x-ray, a kind of snowstorm that fans out across the lungs.

The same precautions for pets generally follows as that for humans, she noted. “Try and keep your pets away if you are digging big holes. Stay on the path and steer clear of sandy soils and beaches.”

Dr. Cooper, chief of staff at the Manitoulin Health Centre and northern representative on the Ontario Medical Association board, was in Toronto for meetings but attended the presentation via teleconference.

Dr. Cooper reiterated the low incidence of the infection “2.4 per 100,000 in the Sudbury/Manitoulin area, we might see two to three cases in a year, but in Toronto, with .29 per 100,000, there are more cases reported.”

The complicating factor in diagnosis, the doctor confirmed, is likely due to the symptoms being “so non-specific.” Dr. Cooper gave an example of an eight-year-old boy presenting at the local emergency department with muscle strain symptoms. “We see lots of kids with muscle strains over the course of a summer,” he said. As to confirmed cases of blastomycosis, however, “I might have seen one or two in my whole career,” he said. “If presented with the symptoms, most doctors would think of the more common things.”

With the long term aspect of the infection, Dr. Cooper noted that it would be something more likely to be caught in a doctor’s office or clinic than in an emergency room visit.

Asked why testing for blastomycosis is not more common, Dr. Cooper responded that it was a great question, and that should something be seen on an x-ray to indicate such an infection, tests should be conducted. But he noted that there are no simple tests that are reliable for blastomycosis, and that the invasive scopes and tissue samples required to confirm a diagnosis have their own complications and are not without some risks themselves. Again, it is in the persistence of symptoms that the case for blastomycosis infection overcomes the weight of those risks.

“I think that I can assure everybody on Manitoulin that if a cough does not respond, we will consider it,” said Dr. Cooper.

When it comes to treatments for blastomycosis, anti-fungal agents have proven effective. “Like with a lot of things, it’s not the bug that kills you,” noted Dr. Cooper, “it’s your body’s response to it, not the virus that gets you.”

Responding to questions on the colour or taste of sputum (phlegm or “spit”), Dr. Cooper noted that there was no colour or odour known to identify the presence of the spores. The depth of a cough that would be required to bring a usable sample of sputum up to diagnose blastomycosis makes it somewhat impractical as an indicator, but remains the most reliable test.

Little Current Anchor Inn co-owner Rob Norris, a local blastomycosis survivor, described his encounter with the infection. He recalled how wife Suzanne had noticed a difference in his body odour while he was battling the infection, saying it was “off.”

But another survivor, John Bowerman of Sheguiandah, was adamant that there were no indications of odour heralding his brush with the disease.

In both cases, the blastomycosis infection was quite advanced by the time it was diagnosed and treated.

The cost of treatment for the disease was anything but reassuring, however. Ms. Norris supplied that the cost to treat her husband exceeded $6,000 and took several months.

The cost of treatment for animals is also quite high, agreed the veterinarians in the room.

Sheguiandah resident Joanne Wade described in heartbreaking detail the loss of her own pet to the disease in 2013, from cross discussion in the room it became apparent that a number of residents had similar experiences.

Concerns were expressed in the meeting that incoming locums (doctors who come in from outside the region to fill in for local doctors at the emergency ward) would not be alerted to the possibility of blastomycosis were recognized, but again, the greater likelihood of the issue being caught over a longer, rather than shorter acute emergency room visit offsets that somewhat.

The danger to those with compromised immune systems was also recognized during the meeting.

There was some question as to why there was not more information available to tourists and visitors to the region at local information kiosks. Ms. Browne noted that the SDHU would be happy to supply the information, should tourism or municipal offices wish to display it.

Following the information meeting, the organizers of the meeting noted that interest in the issue was strong enough to indicate another meeting should be considered, perhaps in the fall.

The final words of the presentation, its key messaging as it were, is to keep perspective as the risk of infection is actually very low, and to stay informed, take reasonable precautions and tell your health provider that you are from a blastomycosis-prone area.