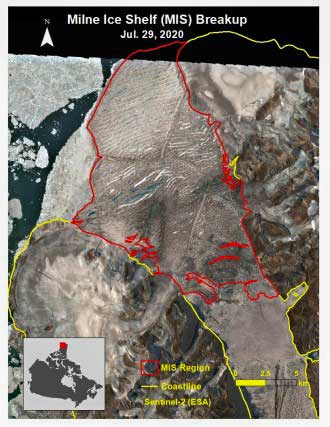

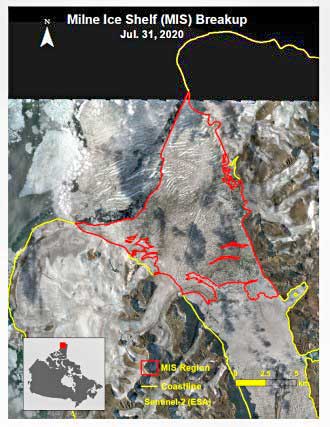

MANITOULIN – The Milne Ice Shelf on the northwest coast of Nunavut’s Ellesmere Island has broken up, reducing in size by almost half and setting large ice islands adrift in the Arctic Ocean. Adrienne White, PhD, an ice analyst at the Canadian Ice Service, Environment and Climate Change Canada who has worked on the Milne Ice Shelf in the past, discovered the event.

Ice shelves are thick floating ice masses attached to the coast. In the Canadian Arctic, ice shelves were primarily formed through the accumulation of sea ice over centuries. The initial break of the 4,000-year-old Milne Ice Shelf took place between July 30 and 31 and reduced the ice shelf area by 43 percent, from 187 square kilometres to 106 square kilometres. One large ice island was created at that time, but it split into two large pieces along with numerous smaller icebergs by August 3.

Dr. White was monitoring the area on the northern coast of Ellesmere Island which is where the calving occurred (a calving event is where a large iceberg or in this case a large ice island breaks off the main body and then can drift away). “Usually in this area we have sea ice (which we call pack ice) drifting around and it’s usually pressed right up against the shelf. For the past decade during the summer we’re seeing open water along this area and when you have open water it’s easier for an ice island to break off and drift away just because you don’t have that sea ice applying pressure against the ice shelf,” she explained. “When we see open water that definitely gives us motive to monitor this area a little more closely. That being said, I wasn’t expecting the Milne Ice Shelf to break up. I considered it to be one of the more stable ice shelves on Ellesmere Island so I was definitely surprised a large fracture cut through it.”

At the start of the 20th century there was a single 8,600 square kilometres ice shelf stretching along the northern coast of Ellesmere Island. By 2000, it had divided into six large ice shelves and several minor ones occupying a total area of 1,050 square kilometres. Ellesmere Island has seen five previous major ice shelf break up events during the 2000s. The Milne Ice Shelf was considered to be one of the least vulnerable to break up since it is well protected in Milne Ford but it has sustained many fractures over the past 12 years.

Prior to this event, the Milne Ice Shelf and the Ward Hunt Ice Shelf were the two largest remaining ice shelves, said Dr. White. There are other small remnant pieces of former ice shelves that are still glued on to the coastline in some places but the Ward Hunt and the Milne are the two largest remaining pieces. “The Milne lost almost half of its area and the part that remains tends to be weaker. It’s much thinner there. The part that broke off is actually much larger ice. It’s between 60 and 80 metres whereas the ice that now remains is much thinner, down to 20 metres, 20 to 30 metres.”

“This drastic decline in ice shelves is clearly related to climate change,” said Luke Copland, University Research Chair in Glaciology in the Department of Geography at the University of Ottawa. “This summer has been up to 5°C warmer than the average over the period from 1981 to 2010 and the region has been warming at two to three times the global rate. The Milne and other ice shelves in Canada are simply not viable any longer and will disappear in the coming decades.”

The Milne Ice Shelf was thicker than other ice shelves so the newly broken off ice islands are 70 to 80 metres thick (for comparison, the wingspan of a Boeing 747-8 is 68.5 metres). The Canadian Ice Service will monitor the remaining ice shelves and track these islands, especially if they drift further south where they can pose a hazard to oil rigs and ships. “The ice islands are currently free floating and mobile; for now, they are confined to the coastline by pack ice,” said Dr. White, but noted they are already starting to drift southwest along the coastline of Ellesmere Island. They can drift into the waterways within Canada’s Arctic archipelago, posing a hazard to ships and they can, in theory, drift into areas where they can collide with oil rigs.

Carleton University’s Derek Mueller, professor in the Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, has visited the ice shelf 11 times since 2004 and was scheduled to visit again this July before his trip was cancelled due to COVID-19. “Our research focus is to learn more about how ice shelves destabilize and break up in a warming climate,” he said in a media release. “We missed being in the field this summer due to the pandemic but we can look at satellite images to track the Milne breaking apart.”

The thick ice of the Milne Ice Shelf had dammed the meltwater at the head of the fjord and created a rare epishelf lake, where a layer of freshwater floats directly on top of the ocean. The lake drained to the ocean underneath the Milne Ice Shelf through a channel that eroded through the bottom. Mr. Mueller and his collaborators at the University of British Columbia and University of California, Davis were studying the flow of water through this channel. “We were amazed to have recently discovered a truly unique ecosystem of bottom-dwelling animals – scallops, sea anemones and so forth – living in the channel,” said Mr. Mueller. “Our team was on the cusp of further documenting this unique environment which may well have disappeared as a result of this collapse.”

“Ice losses in the Arctic demonstrate that things we change around our local area have real impacts in the rest of the world,” Dr. Copland said. “Global warming is primarily driven by increases in carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, so if we can reduce how much each of us produces, for example by driving more fuel-efficient cars, then the whole world will warm less.”

“The Arctic is a bit of a canary in the coal mine,” said Dr. Copland. “Things that are happening there now will happen down south later. The warming that’s driving ice shelf losses in the Arctic now will occur in areas such as Manitoulin in the future. Most people already have their own memories of how the local climate has changed compared to when they were kids, or when their parents were kids: typically winters were longer and snowier, and summers were cooler in the past. If we continue on our current trajectory, then in our local towns there will be even less ice and snow in the future and more hot and sticky summers.”

“This calving is showing us that our Arctic is warming rapidly. The Arctic in general is warming at twice the normal rate of the rest of the world,” Dr. White said. It’s called Arctic amplification. The Arctic has been warming at approximately 1°C per decade. The Arctic and the Antarctic are very opposite in a lot of ways: the Arctic is basically the ocean surrounded by land whereas the Antarctic is a continent surrounded by water so the way that a warming climate will affect them is very different. The coastal regions of Antarctica have also seen a lot of warming which has led to the ice shelf losses that we’ve seen there.

“While I understand that it’s difficult for people to understand to make that connection to why a warming Arctic should concern us, I can only give you a brief answer because I’m not a climatologist,” she said. “The Arctic and the Antarctic are basically the air conditioners of the planet so if you warm the Arctic it will have an impact on the weather systems we see elsewhere (including where you are on Manitoulin Island). A warming Arctic can lead to effects on the weather that we see down south such as some of these extreme weather events that we’ve been seeing such as extreme snowfall, drought, heat waves, so the weather systems are all connected. When we have warming temperatures, for the Great Lakes especially, that is going to have an impact on both evaporation and precipitation which inevitably will have an effect on water levels so that’s something someone from our climate change division can give you more information about. There’s also changes in the lake ice conditions in the Great Lakes so a lot more open water, especially this past winter.”

Dr. White fell in love with the Arctic as an undergraduate student in geography. Her first visit was in 2010. “I went up there seven years and throughout that time I absolutely saw changes,” she said. “My first study for my masters focused on the Peterson Ice Shelf, of which over 50 percent of that ice shelf is now lost. Part of the reason for focusing on the Milne Ice Shelf for my Ph.D. was knowing it would still be there by the end of my Ph.D. To see now that a large ice island has broken off, I’m not surprised. Shocked, but not surprised is the way I would put it. It was inevitable.”