Eye witness accounts of the sinking of the Queen of the Great Lakes 70 years ago

MANITOULIN—The telegram announcing the survival of Harold Allen arrived at the Gore Bay school house (now the site of the Manitoulin Lodge) 70 years ago today (June 7) and made its way to his brother Stan, a 10-year old foster child who had already experienced an incredible burden of woe—being a foster child growing up in rural Gordon Township in the 1940s was no picnic by anybody’s definition.

For a few days following the grounding and loss of the bulk carrier Emperor little was known of the fate of the crew.

“They didn’t have the complete list of who had survived yet,” recalled Mr. Allen, who along with the rest of his surviving family and friends remained in suspense. “When my brother got off at the docks, just down by where McQuarrie Motors is and walked up the street past the school, people were lined up the side of the street to shake his hand.”

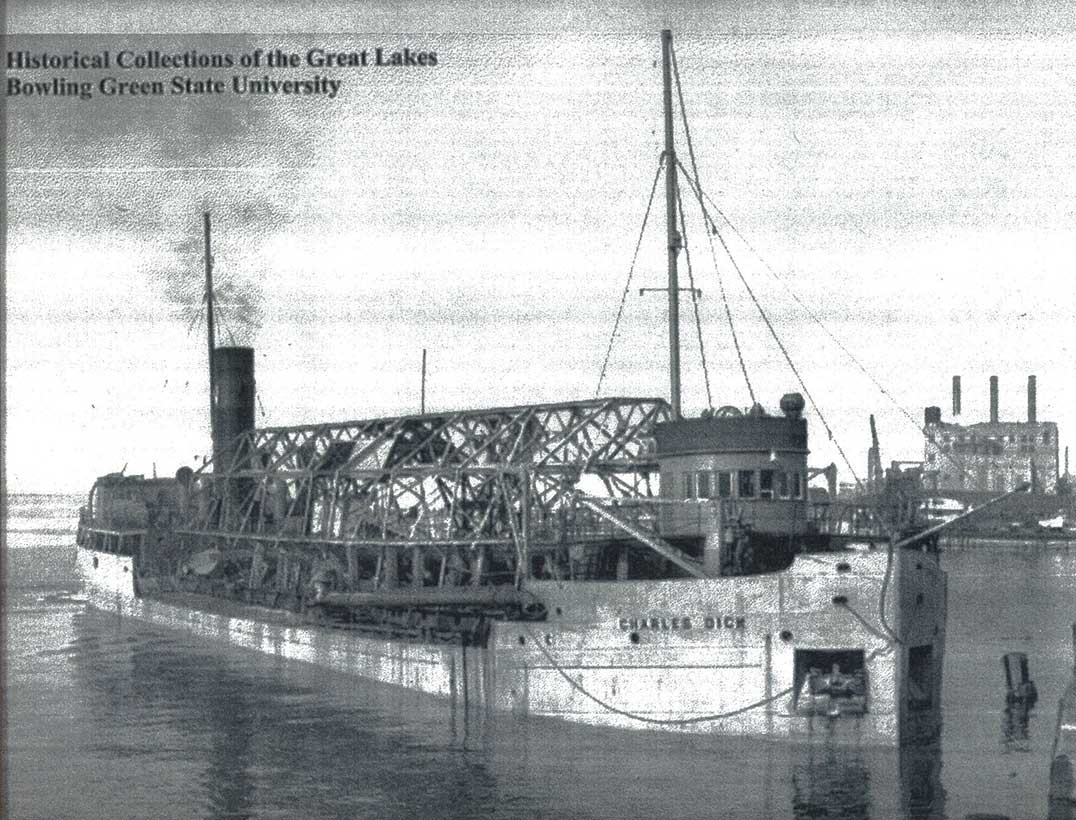

Built in 1910 at the Collingwood Ship Building Company in the Ontario town of that name, she was registered in March of 1911 at Midland by Inland Lines Ltd. Shortly after, in May 1916, the Emperor was purchased by the famed Canada Steamship Lines of Montreal.

She was a beauty, bulking out at 7,031 gross tons, 525 feet long and 56 feet in the beam, with a Scottish-built 1,500 horsepower triple expansion engine that could move her along at the less-than-princely speed of 11.5 nautical miles per hour. At the time of her launch, the Emperor was the largest vessel ever built in Canada.

In those days an Island boy could well find himself a career in the merchant fleet plying the Great Lakes waters, both Mr. Allens certainly did, as did a lot of their friends and neighbours.

The Emperor came to grief at 4:45 am on June 4, 1947, 70 years ago this past weekend, when she “ran hard up on Canoe Rocks, on the northwest side of Isle Royale,” according to ‘The Inland Seas: Journal of the Great Lakes Historical Society.’ Barely 25 minutes later, the mighty laker had foundered, splitting in two with her fore standing in 25 feet of water and her stern lying 150 feet down. A number of her crew that never made it off are believed to be entombed within her hull.

There were 33 crew aboard the Emperor, 21 rescued by the US Coast Guard Cutter Kimball, 10 in a water-filled lifeboat, four found clinging to a second overturned lifeboat and seven found on Canoe Rock itself. There were 12 crew lost, including Captain Eldon Walkingshaw, a 42-year veteran of the Great Lakes trade and the first mate James Morrey, who was on duty at the time and three female stewardesses.

Harold Allen recalled the hectic minutes before the sinking that took place 60 years ago and he remains convinced that there were actually 13 lost that day. As to how the three stewardesses were lost he is puzzled. “I helped them put their life preservers on,” he said. “I tied them myself, so I don’t see how they could not have been floating on the water.”

The clue may be in the confusion that took place at the lifeboats. “The third mate was from Poland and he was used to being in the navy,” recalled Mr. Allen. “The chief engineer told him to put the boat in the water, but the third mate wouldn’t do it until the captain gave him the order to abandon ship.”

As Harold Allen and his companions watched the stern of the ship break off and sink into the depths, dragging the bow down, the doors which had been wired open were snapped shut by the force of the water. “We watched them snap shut one by one,” he said.

Some of the crew were later found within the ship. Mr. Allen and a companion whose name is lost to the 88-year-old in the mists of time, set out through the debris in their lifeboat seeking survivors, and found one person clinging to a life ring. “We found another fellow clinging to the wooden steps that we used to go up and oil the dynamo (a type of generator), that was what pulled him up to the surface and allowed him to survive,” he said.

Later, when the Kimball arrived and the survivors were pulled aboard, Mr. Allen implored him to continue the search. “I couldn’t believe we could possibly have lost so many,” he said. “The captain graciously agreed and we did a circle of the area.” But all that was to be found was the body of one of the cooks. “I thought it was my friend the second engineer, because they were both big people. But it wasn’t.” His friend was discovered later by divers in the engine room of the ship.

In those days there were a lot of Island people working on the ships, following the ebb and flow of the work from ship to ship. Mr. Allen found himself shipping back out shortly after he got home from his harrowing experience.

Thus it was that he missed the inquiry into the sinking of the Emperor, something that still bothers him to this very day. Another survivor, John Leonard, was working as a wheelsman on the Emperor when it went down had no one to back his version of the events. Something Mr. Allen would have preferred to explain to him. “I was in Thunder Bay when I got the letter,” he said. “I didn’t have the money to take a cab to Toronto and the bus wasn’t leaving in time to get there.” Mr. Allen sent a note to the inquiry explaining his situation, but he never heard back.

Stan Allen later worked with Mr. Leonard who was by then captaining a commercial sand sucker, but they never discussed the events of the Emperor. “I think he knew I was his brother,” said Harold Allen, “but he might have been upset that I wasn’t there to back up his side of the story.”

The details of Mr. Leonard’s story and how it differed from the official accounts are not readily available, but maritime historian Buck Longhurst, a good friend of Mr. Leonard said that he remained angry with the captain onto his dying days. The inference being that while the inquiry exonerated the captain in the loss of life, Mr. Leonard was of a different frame of mind. The mate who was on duty steering the ship was exhausted by his earlier duties and did not have experience steering a larger vessel such as the bulk carrier. By all accounts Mr. Leonard was a good captain, a good friend and someone who stayed rock solid in the face of any crisis.

Life and loss on the water were common experiences in those days working on the Great Lakes, but today due to ever increasing ship sizes and the advent of automation, those jobs are fewer and far between.

“They replaced the old ships three to one with the new ones,” said Stan Allen, who served his career on the lakes.