Long past his bedtime, a 10-year-old future chief of Wiikwemkoong peeked down through the return air vent above the living room in his grandfather’s house at the man who was to become his mentor, his friend and colleague playing music at his uncle’s house.

“It was the only time in my life I ever looked down on Hardy Peltier,” laughed Eugene Manitowabi. “He was a pretty tall man.”

Albert Peltier passed away December 19, 2016 at the age of 78.

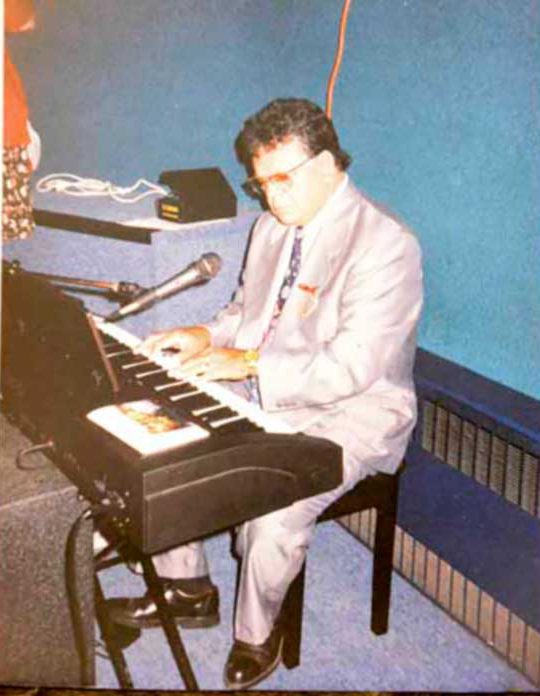

Albert (Hardy) Peltier was only 16 or 17 at the time, and although most know the late Northern Ontario Country Music Hall of Fame inductee for his guitar playing, he was playing the piano with a group of local musicians. “He was quite a piano player,” recalled Mr. Manitowabi. Coming from a long tradition of musicians, Mr. Manitowabi said “Hardy had it in his genes.”

country classics, Hardy Peltier was an accomplished piano player.

But of those stolen late night moments watching Mr. Peltier and his friends and family play around his grandfather’s dining room table, “I have to say, that was the absolutely best music I ever heard.”

Mr. Peltier was born in 1938 in a house next to the ball field, that’s Thunderbird Park, in Wiikwemkoong. “It was eventually sold when my mother died,” noted Mr. Peltier in his memoir. “I was only about two years old.” Mr. Peltier’s mother died in childbirth. “It was quite an experience for a two-year-old to see a mother die,” he recalled later in life. “Some things you couldn’t avoid. There were no doctors in the day.”

Mr. Peltier’s father felt the burden of blame for his wife’s death, however unfairly, and it would over a decade until he reunited with his father who left to find work in the camps in Michigan.

He was brought up by his grandparents, who were living on a meagre monthly pension. “But we survived,” he recalled. “My brother Felix and my sister Stella.”

Mr. Peltier remembered those days as being good. “Every Sunday, every holiday, all the relatives, Andrew Oshkawbiwesens, Joyce, John Jacko, Frank Jacko and many others would come into Wiky on their sleigh horse in the winter and in the summer on their wagon; it was a good family affair. We kept very close together, there was no alcohol in our lives—except for my uncle Ernest. He was a businessman, he died of alcoholism from moonshine.”

Like many children who grew up in relative poverty, Mr. Peltier said it never occurred to them that they were poor.

Some of Mr. Peltier’s earliest memories were of sitting on the docks down by the bay waiting for the boats to come rowing in from Chesaabing (the big net). “We had to go bum up our fish,” he recalled. “Three or four whitefish in order to survive.”

Brought up by the nuns in the school in Wiikwemkoong, Mr. Peltier expressed a lot of gratitude to the sisters. “They helped us survive in my household,” he said. “The nuns used to come to our house and feed us some cookies, even the old army cookies, the rations, but it kept us alive.” It was Sister Loretta, the cook, who first taught Mr. Peltier to play the piano.

His grandmother also had an organ, an old pump. “You would pump the heck out of it, a big bellow that produced a sound through the air system, just like blowing on a Scotchman’s bagpipe.”

Mr. Peltier’s grandfather worked for the nuns, in the furnace room or doing chores in the winter.

children.

One of the big differences in growing up as a teenager in Wiikwemkoong in those days was that there was no alcohol and a lot less to do in the way of recreational activities. Although he did not excel in school, when he was 15 years old Mr. Peltier was sent to Garnier College in Spanish.

Although he first met his future wife Sara at the residential school, he didn’t recall that until much later in life. He left school not long after arriving and began to roam in search of work, spending much of his time in the bush camps of Northern Michigan with his father.

“I was the first drop out,” he recalled. “We jumped out of the window and took off. Nobody chased us.”

Despite that early exit from school, Mr. Peltier was a lifelong learner, graduating with a number of certifications including earning his certification as a community health worker in Hobema.

When he returned home to Wiikwemkoong, his grandparents were gone, he lived for a time with Henry Peltier, working out of a logging camp in South Bay. It was Henry who taught him how to play the guitar. His first chord was a G and the first song he mastered was the Hank Williams’ standard ‘Your Cheating Heart.’

From the James Bay coast to the halls of power in Ottawa, most people who knew Albert Peltier express surprise when they discover his first name wasn’t actually Hardy. In fact, Hardy wasn’t even any part of his birth name. It was something that the late Mr. Peltier took some amusement in. “Every Sunday, up the building were the old DayStar is located now, we used to have movies, the Green Hornet and Tonto and the Lone Ranger,” he recalled. “A fellow by the name of Bill Porter of Gore Bay would come up and set up a movie on Sundays. There was a series, Laurel and Hardy, and Gordon said to me ‘you are Hardy because you like that movie,’ and I said yes. Unbelievably, nobody knows my real name.”

“All those people he worked with in Ottawa, all the big shots and big wigs in the government, they all thought his name was Hardy,” laughed Mr. Manitowabi.

Mr. Peltier recalled going to the Rabbit Island home of Ambrose Corbiere to help him with his will. “He kept looking out the window,” recalled Mr. Peltier. “I said ‘ahnii geh? (what?).’ ‘Albert,’ he said, ‘I am waiting for Albert Peltier, he is supposed to be here from the band office. I looked at him and said ‘Ambrose, look at me, I am Albert Peltier.’ That was so funny.”

Larry Leblanc was the education director in Manitowaning when he first met Mr. Peltier. “It was in the early 70s. We had a bit of money to hire a researcher,” he said. “All of the old records for the Indian Affairs office were in our basement, stretching all the way back to 1836. In those days, there was no interest.” Mr. Peltier was hired as Wiikwemkoong’s Land Adminstration officer.

Mr. Peltier threw himself into what was to become his life’s work and a vocation that was to have far-reaching consequences for Wiikwemkoong that are still playing out. “A couple of years later he transferred over to the UCCMM when it was formed,” recalled Mr. Leblanc. But by then the two had become fast friends, often travelling with their wives around the country to different events, concerts and locales on vacation. Mr. Leblanc would assist Mr. Hardy with deciphering the stolid and archaic English that was common to the old documents. “A lot of it was in script and was really hard to make out,” recalled Mr. Leblanc.

Bit by bit, piece by piece, Mr. Peltier put together the story of Wiikwemkoong and its people. When he had exhausted the trove in the basement in Manitowaning, he moved on to the National Archives and other depositories of official documents. As he chased down the ancient references, like an Anishinaabe George Smiley, hot on the very cold trail of the historical proof of which Islands were used for fishing, which shores were temporary camp grounds on the annual migratory hunts, and the many interconnections with distant bands.

“He found the documents that proved that they did use those Islands,” said Mr. Leblanc.

Daughter Mary Jo Wabano recalled her father’s many long and frequent absences as he travelled to Ottawa, Toronto and dozens of First Nations communities, hunting down the references that would lay the foundation of what was to become the Wiikwemkoong Islands claim and the earlier Point Grondine annexation to the Wiikwemkoong land base. It was his research that formed the basis for the 1990 Manitoulin Land Agreement that saw Island First Nations finally receive compensation for the shorelines and road allowances that had been transferred to Manitoulin municipalities.

“In everything I did while I was chief, Hardy was right there beside me,” noted Mr. Manitowabi. “He was my co-conspirator, my confidant and my mentor.” It was a sentiment shared by many former chiefs and band officials through the years.

But Mr. Peltier’s dogged hunt for supporting documentation for Wiikwemkoong’s land claims was not without its frustrations.

“Every couple of years there would be a new band council elected,” recalled Mr. Leblanc. “He would have to go through it all over again, explaining what was going on, where things were at, why things were the way they were. It really took a toll on him.”

But even more frustrating were what he termed the legions of “boy lawyers,” young law school graduates hired by the federal government with one simple goal in mind. Stall.

“It was pretty simple really, the federal government has so many land claims outstanding that they couldn’t begin to pay for them all at once,” recalled Mr. Leblanc. “They have a strategy of just settling a few claims at a time and stalling all the rest.”

Mr. Peltier was very well respected by the officials in Ottawa and Toronto, but the “boy lawyers” were another matter. “He wasn’t above playing the ‘dumb Indian’ role to get his point across to them,” said Mr. Leblanc. “He was probably the smartest man in the room, but he would play the part to get what he wanted out of them.”

Mr. Peltier ran into racism throughout his life, both overt and the subtler kind that those practicing it don’t even realize they are engaged in.

“We were out at a bar on the North Shore where Hardy (and the rest of the Odawas, the band he formed with friends from the community) had found a gig for us,” recalled Mr. Manitowabi. “I was talking to one of the people who had come out to see us and asked him what brought him out. He was pretty blunt about it. ‘We came to see you fall on your face’ the patron admitted.”

In those days, most whites believed that Anishinaabe were inherently alcoholic and unable to tolerate the white man’s drink—never mind that plenty of “whites” can’t either. Mr. Peltier and the Odawas brought the house down that night, and plenty of other nights in venues stretching across the North.

For his part, Mr. Peltier held a traditionally inclusive view of what made an Anishinaabe. “He never made me feel any less,” said Mr. Manitowabi. “He helped a lot of people get their status back.”

Mr. Peltier was more than simply a musician. He was a full on entertainer, filling the stage and bringing the audience into his world and the music along with his band. “He didn’t believe in just getting up there and playing a song like some guys,” said Mr. Manitowabi. “He always had a story to go along with it.” His was a rare talent, but not one that he lorded over anyone.

“He never made you feel unwelcome,” recalled Mr. Manitowabi, himself a noted local musician and entertainer. “Hardy gave me my first opportunity on stage.” He never minded sharing the spotlight with others and was always there to encourage younger musicians.

“I remember him sitting in his truck at Thunderbird Park watching people perform,” recalled Ms. Wabano.

Mr. Peltier had a tremendous facility for translating historical context for the people on the other side of the table. “He understood life back in those early days, so he could take people back to what a resident of Wiikwemkoong would have been doing at any time of the day or week. He got that from his own life experience and his work in the historical archives. There was nobody alive today that knew that history like Hardy did.”

One of Mr. Peltier’s regrets in life was that he did not live to see the conclusion of the Islands claim. “He really felt the band should have been more aggressive with the government,” said Mr. Leblanc. “He felt they should have pushed them harder. He was worried that people would forget the work that he did and all that he had accomplished—that the people who came after him would get all the credit for his work.”