Murchie Wright

Murchie Wright is a fine gentleman with a generous spirit and a kind heart. His current abode is the Manitoulin Centennial Manor. He has a comfortable room there where he can enjoy his quiet time and exercise his computer skills. This retiree never gives up an opportunity to share a few stories with a friend. He has led a busy, colourful life that started on the east coast and eventually brought him to Manitoulin. He realized the treasure he had here and was compelled to put down roots and stay. Murchie loved to use his ingenuity to modify and fix almost anything. “He worked hard at everything he did,” son Greg attests. “There is not a lazy bone in his body. Dad was always building things and gadgets for his kids, including go-cars, boats, motors, dune buggies and swing sets.”

Murchie was born to Myrtle, nee Turner, and Hubert Wright in Arthurette, New Brunswick on January 10, 1931. “I was named after Murchie Roberts Turner, an uncle I never met. He was a civil engineer and he helped build the CPR railway between Andover and Plaster Rock in New Brunswick. Part of an earlier CPR stretch ran close to my great-grandfather’s homestead. In the late 1800s, long before I was born, a wood-fired train rambled by his home and the sparks from the engine started his house on fire. I had never heard of a train starting a house on fire before. The family built another house closer to the road and further away from the tracks. When I was a little older, I loved putting dimes on the tracks to see how they looked after being flattened.”

Murchie had an older brother, Marvin, and a younger brother, Harry. His little sister, Madeline, died at age 12 of mastoiditis, a leading cause of death in children before the discovery of antibiotics. Marvin became a contractor and worked on many jobs; younger brother Harry joined the Air Force and served in New Guinea and Europe as an electronics and electrics technician. He helped assemble the first Harvard trainers and single engine Beavers and Otters for his RCAF pilots.

“My parents lived in the northern part of New Brunswick, in Perth-Handover, near the border with the States. My dad was a fruit and vegetable inspector for the government. He travelled to many farms and checked for problems the farmers faced, including potato diseases, a serious issue for eastern Canada.”

“I loved to lie in the grass and read. Sometimes I would look up in the air and wonder how far I could go up. My mind loved to wander. I think that helped me become comfortable being alone. A perfect day was reading or day-dreaming and seeing nothing bad.” Hockey was never a favourite pastime in the winter. “We did give it a good try on the river from time to time. If you missed the puck, either a chunk of bark or a horse turd, it would take forever to retrieve it, either from a distant snow bank or a quarter mile down the river.”

“I used to hunt for birds with the family’s .22 rifle. My mother would ask me to fetch some partridges for supper and I would reliably bring back two big ones and a smaller one. They were so plentiful on our farm.” Murchie also loved to fix anything he could find. “I fixed bicycles and other stuff so became a bit of a hoarder, collecting parts and items to fix. My mind was always inquisitive, wondering how I can best repair the item.” He also liked to make toy revolvers out of wood.

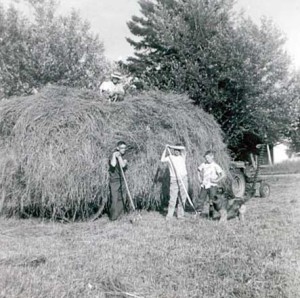

circa 1940.

One summer, the young lad had a blind deer for a pet but when the days got shorter and colder, his dad had to put the fawn down because he knew it had no chance of surviving in the wild. “That was a tough day,” Murchie confirms. “We had pigs too and I loved to feed them some of mum’s apple cider that had gone bad. The pigs would get drunk, run about, squeal a lot, and fall down. It was great fun if nobody found out.”

In the early 1940s, at 10, Murchie was deployed for the war effort. He was asked to count and identify airplanes flying over his house. “I had to call a central number and report any sightings. I got to know, quite well, the 10-engine and four-engine bombers that came from the American air bases. My dog Buster liked to chase the planes when they came into sight.”

In his mid-teens, Murchie was diagnosed with tuberculosis. “I spent my 16th birthday in the local hospital. Marvin had come home with the disease and unwittingly infected me. In fact, Marvin had just recovered and left the hospital bed that I got into. We found out I had the same malady when I developed pleurisy. Pleurisy was common in people infected with tuberculosis.” Murchie still shudders when he recalls the needle they used for the pleurisy. “It appeared to be three feet long.”

At that time, it was believed only fresh air and sunshine could help with the healing of this disease. It was winter so the room was very cold. “We often woke in the morning with snow on our beds.” The teen spent nine months in a ward with 16 people, most of them very elderly and slowly dying. He was the youngest one in there. “That was frightening experience, but I survived.”

Current on his far right.

While Murchie was in the hospital, his high school burned down. “When I got home, a new high school had been built. He had to take a provincial exam after Grade 11. There was no Grade 12 at the time. “I was optimistic that I would do well.” Murchie had achieved honours in math but this provincial exam had been standardized and perhaps not correlated with all the local curricula. The test was so challenging that only one person in the class passed it. Nevertheless, Murchie, the only boy in his class, was still part of the first graduating class for the new school. He was scheduled to give the valedictorian speech. “I got up to speak but I choked up and couldn’t find my voice, so I asked one of the other students to read it. She did quite well on my behalf.”

The New Brunswick lad left school and worked with a land surveyor that summer. “I really enjoyed the concept of working with grades of land and finding distant level spots. It came easily to me while some of the engineers found it difficult to comprehend at first, but this was just a summer job not a career move.”

“My aunt Hazel wanted me to be a teacher and she suggested I board with them while attending classes. They lived in Andover, near the States. I had different ideas; I really wanted to be a mechanic, to fix things, and I finally convinced my family. Thankfully, my mother and Aunt Hazel decided to help me reach that goal. They arranged for a move to Toronto instead, to train with my uncle who had a car dealership. I would apprentice with him, learn to repair cars and take some courses at Ryerson.”

At about this time, the Wright family adopted a little girl from a nearby orphanage in St. John’s. Sandra had developmental issues related to a problematic forceps delivery. She was a sweet little girl and a baby sister to the Wright children. Before Murchie left New Brunswick, he found someone else he liked of the ‘long-haired people we share the earth with.’

Her name was Margaret and the two had met in school before. “She was five years younger, only 17, so we needed a letter from her parents to marry. I bought her a ring, she came to Toronto, and we were married on May 31, 1952. Our wedding photos were taken on Uncle Harold’s and Aunt Gertrude’s verandah. I think that was the only time I ever smiled for a photo. I find it really hard to smile on demand.” There was no time for a honeymoon, the groom had to get back to his training.

The decision to apprentice in Toronto had been made quickly. This opportunity was not available to anyone over 21 years of age and Murchie was already 21. Uncle Harold and a friend of his helped by declaring him to be 19, to give him some breathing room.

Life in Toronto was exciting and there was always lots to do. By the time the couple had two children, they decided they had to find a bigger place. A house on the west end of Toronto fit the bill and they rented it for six years. “Eventually, we realized it was just too expensive to live in Toronto.”

“In 1957, I got a job at the General Motors’ dealership in Little Current, ACME Motors, so we moved north. I could have gone to a Ford dealership in Parry Sound but we decided to try Manitoulin. I remember stopping at Whitefish Falls by the big hill there. Margaret looked around and started to cry, upset at the rough road and the abundance of trees with little else to show. We thought briefly about going back to Toronto but decided to forge ahead. Once we settled in Little Current, which seemed like New York City after all those trees in the Whitefish area, we quite liked our surroundings. I stayed with Acme Motors for 25 years.”

Baseball became a favourite sport in the early years on Manitoulin. A few of those early baseball trips to Killarney were on Justin Anglin’s work boat. Fastball in Little Current was a popular sport, attracting several teams, including Ellis Cleaners and the Legion. Murchie helped out with Little League baseball and softball in the 1960s. He and Charlie McCulloch coordinated and built the first ballfield at Low Island with volunteers and donations. The CPR helped by loaning some of their heavy equipment.

Mitchell and Kevin were born on Manitoulin and the Wrights became a family of six. The family made a terrible discovery when Margaret was just 37-years-old. She had developed malignant melanoma and it was in a later stage which made it challenging to cure. Murchie spent a lot of time driving to Toronto to see Margaret, often accompanied by his mother-in-law and his sister-in-law, Glenna.

He witnessed the CN Tower being put in place in Toronto while driving on the Queen Elizabeth Way. It was a momentous occasion and it gave him something else to focus on for a few minutes. “For Margaret, they tried all kinds of new experimental meds, including a form of chemotherapy, but nothing worked in the end.” Sadly, Margaret died at age 42. It was very hard on Murchie and the children. In time Murchie found a new partner. “I really liked my mother-in-law so I wound up marrying her other daughter, Glenna,” he adds, smiling. “She already had six kids of her own, so we became a blended family of 12.”

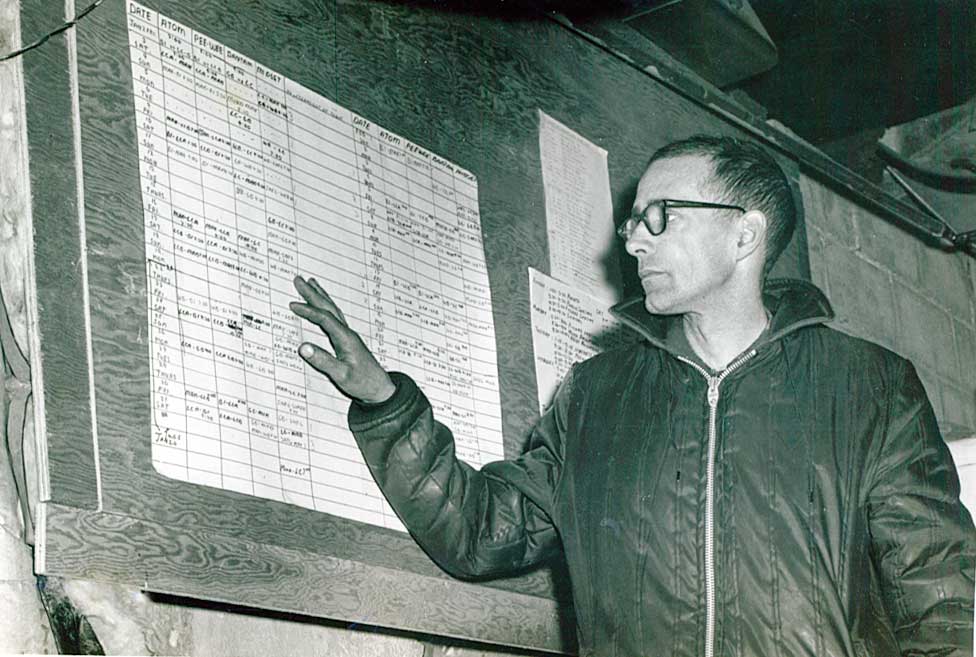

After Acme Motors, Murchie got work with the Canadian Pacific Railroad. He wanted to apply for a teaching job, training mechanics at the high school in West Bay, but he needed Grade 12. Instead, he decided to become the shop foreman for the repair shop for CPR and he wore his white cap proudly. “We fixed what they broke for 10 years.” Murchie became a highly valued employee because he and his team got very good at repairing all the machinery.

The CPR shipped iron ore pellets from INCO to Chicago and Detroit via the CPR coal dock in Little Current. They used self-loaders to fill the holds of the big ships. After they pulled out their operations in Little Current, there was a plan to build a recreational area over the industrial land at Goat Island, across the channel from downtown Little Current. They planned a ski hill and a swimming pool but that didn’t happen, likely due to the costs involved. They did clean out most of the coal and later the iron ore.”

Murchie partnered with Ross Blum and operated M & R Shell at the top of the hill, where the Hilltop Shell station is now located. This business burned in the late 1970s and Murchie returned to Acme Motors for a spell until a back injury made this work impossible.

Hockey was also a favourite diversion. Murchie worked to bring Jr. Hockey to Little Current and the Island in the late 1960s. The Manitoulin Islanders survived for three or four seasons. He was a key volunteer for the Little Current Minor Hockey League for many years. “We picked up the kids after school and headed to Elliot Lake, Blind River or Spanish. Often we wouldn’t get them home to the West End of the Island until three in the morning.” Occasionally, AJ Bus lines would donate a bus. At the time, Murchie’s family claimed he spent too many hours at the rink.

Others must have noticed his hard work. About 1970, Murchie was honoured as Citizen of the Year in Little Current. He became a member of the Little Current Recreation Commission, a volunteer support committee for the town, eventually becoming their chairman. Murchie is proud that he was part of the group working with the late mayor Allan Little and his council to get artificial ice in the old arena. That arena sat where Valu Mart is now. Before the artificial ice, Murchie kept his players in shape with basketball in the off season. “It was a bit of a challenge teaching them this game. The artificial ice made the conditioning task easier.”

Murchie had a bout of heart disease in his 50s and had to leave work after the bi-pass surgery. “The shock of the surgery seemed to affect my memory and made my supervisory work for the CPR more difficult. I got a disability pension from them and I retired.”

The children all did well. Gregory got his degree in Biology and Environmental Sciences from Waterloo and worked for the town as manager of community services. Mary Lynn, his wife and a nurse, spent many years working at the Manitoulin Health Centre. Prior to her retirement, she was director of nursing care for the Island’s two hospitals. Terry drives a loader for Pioneer Construction in Sudbury. Murchie is also a proud great-grandfather again. Mitchell worked at the Dennison Mine and the Ontario Hydro Nuclear Plant at Pickering. His wife Shelley works in home care. Kevin has his own business fixing roofs. He lives in Kagawong.

“I have macular degeneration now from a baseball thrown by a left-handed pitcher many years ago. I misjudged where the ball was going and got it right in the eye. I thought it would curve away from me, but I was wrong.” Murchie also has Charles Bonnet Syndrome, a common condition for people who have lost their sight. It causes him to see things that aren’t really there, known as visual hallucinations. The brain sees two images of everything and tries to align them.

His older brother Marvin later moved to the States, the place of his birth, but he never really got over the tuberculosis. He found a wife. He bought a van and got portable X-raying equipment and got a job helping others with the disease in the States and in Mexico.

“My favourite television show is the Big Bang Theory. When I was younger, I found the canned laughter was irritating, especially when I was trying to fix stuff. I couldn’t focus, so I always asked my kids to turn it off. Now I get a kick out of watching the reruns,” he comments, smiling. “I can’t read anymore and even reading my calendar is hard. The squares are so small. I can see the numbers but the writing is almost impossible when you see double,” the elder shares.

“Looking back, there isn’t anything I still want to do that I haven’t done already,” he insists. “I love all the seasons; each has something unique and wonderful to share. I could fix bicycles or snowmobiles so I was busy all year. My strengths have always been diagnosing and fixing cars. In my later years, computers took over and did much of the diagnosing. I taught myself how to use a computer and took pride in being able to do the work and keep the number of mistakes low using new technology.”

“I am not afraid of much now,” Murchie adds with certainty, “except calling my grandchildren by the wrong name. I am proud of my children and grandchildren and my great-grandchildren. The only regret I have is swinging at that curved pitch that damaged my eye.”

“I have never been sorry that I came here. It kind of reminded me of my early years in New Brunswick, living at home, on our old farm. I have always enjoyed being in a small town. My kids did most of their growing up here. I got my first real job here so Manitoulin has always been important to me. It was also much more affordable living on the Island than trying to make a go of it in Toronto. Manitoulin is a special place for me and that is why I am still here today, living in the Manor.”