For over 50 years in medical practice and well into retirement, Dr. Bailey built many cultural bridges

by Michael Erskine (with files from Petra Wall)

When John Francis Mills Bailey came into the world, on June 2, 1923, the anticipation was that his destiny was to follow in the footsteps of his great grandfather, grandfather and father to become the custodian of the family farm in Omemee, a small community just outside Peterborough, Ontario. Jack Bailey had other plans.

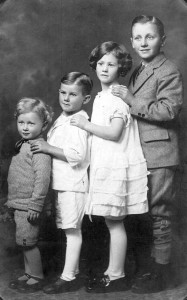

At age 10, the second of the Bailey children (Aldon, predeceased, Thelma and Howard, predeceased) was walking down the main street of Omemee while holding hands with his Aunt Eva when he first declared his coming vocation. His aunt asked him what he wanted to be when he grew up. Barely pausing for a breath the young man declared, “I want to be a doctor.” Dr. Bailey often cited her response as providing the seminal impetus that would sustain his determination to attain his goal, “I think you will be good.” Dr. Bailey admitted that his aunt was probably being more kind than prophetic, but perhaps his aunt simply already saw glint of steely determination in her young charge’s eyes that would sustain him through the career challenges that lay ahead.

There were definitely challenges. As was very common in the early years of the 20th century, Dr. Bailey’s parents had not completed high school. A primary education was generally seen as being plenty of schooling for the business of successfully running a farming operation, and it was. So before heading off to high school each morning Dr. Bailey had to milk five cows, and the same five cows awaited his return in the afternoon.

To raise money for school, Dr. Bailey raised chickens and took a job at the Dominion Canning factory in Omemee. His hard work and determination at the factory won him another champion in his boss Mr. Massey. His supervisor was to play a key role in opening the doors for the future physician. He encouraged Dr. Bailey to finish his Grade 13 and when the fall harvest led to his late arrival to begin classes, it was Mr. Massey who vouchsafed him back into school to finish Grade 13. Dr. Bailey repaid that faith by attaining marks in the 90s that year (not surprisingly agriculture, 97, was his highest mark, but music, 91, played a fairly close second).

When Dr. Bailey sought a bank loan to pay for his tuition, the young farmer with no collateral was about to be turned down until Mr. Massey once again stepped in to back him personally as good for the loan. Going even further, the supervisor personally loaned him $600 to purchase a car. The medical school at the University of Toronto was a very long way off in those pre-war years.

With empathy that was to mark his entire life, Dr. Bailey noted that as challenging as it was for him to attend school, being male gave him a big leg up. He attended classes at the same time as the wife of insulin co-discoverer Dr. Charles Best.

School stopped during the war years, and while his older brother headed off to war as a soldier, Dr. Bailey played his part in assisting in the war effort by returning to the canning factory. An army marches on its stomach, so the saying goes.

After graduation, the newly minted physician cast about for a place to set up his practice. He had three criteria. It had to be a village or small town, it had to be on or very near the water and it had to be in the North.

A physician from Capreol, Ontario contacted Dr. Bailey and invited him to come and visit that town (then the bustling central railway hub of Northern Ontario). While there, Dr. Bailey decided he would like to see Manitoulin Island. Unfortunately for the erstwhile recruiter from Capreol, agreeing to take Dr. Bailey for a visit was to prove to be his undoing. Dr. Bailey immediately fell in love with the Island. He moved to Little Current in 1948 and steadfastly refused to budge from that day forward.

The Manitoulin Island that Dr. Bailey moved to in the early years following the war was a vastly different place than it is today. Many people still travelled in vehicles literally propelled by horse power and the Little Current Swing Bridge had only opened to automotive traffic three years before. There were three small hospitals and only four doctors to service a population that has not changed much from the present day.

The practice of a rural family doctor was a universe apart, however.

The stories of Dr. Bailey from his early days on Manitoulin are the stuff of legend, a true pioneering doctor, he left behind a legacy that impacts the community’s health services up to the present day. There are a handful of doctors on Manitoulin who were known by the affectionate honorific of “doc.” Old Doc Bailey is the last of those beloved figures. Today’s doctors are highly honoured, of course, but there just seems to be a greater distance, implied by the more formal title of doctor, that Dr. Bailey and his contemporaries transcended.

Perhaps it was his insistence on travelling to the First Nation communities, like Wikwemikong, to deliver his services. The willingness, the insistence in fact, to stay overnight to watch over a precarious patient in the hospital or in some remote wooden shack far back in the bush or on some isolated island that could only be reached by early floatplane or boat, often in weather that would place a green tint on even a seasoned seadog’s face.

Dr. Bailey married Island schoolteacher Joyce Isabelle Tindle, the daughter of the onetime Little Current Anglican minister, at a service in Toronto and there followed in succession four boys, Chris, Peter, Mike and Geof.

taking to the air and waves in weather that often proved daunting.

Geof and Mike Bailey described growing up in the family of a driven rural doctor. “We were raised mostly by our mom,” said Geof. “He was generally very busy.”

“Our father had things to be done,” agreed Mike, “and he had been brought up to be driven.”

Lists played a big part in their lives growing up. “Every Saturday morning there were long lists of chores that had to be done,” recalled Geof. “But we had fun,” noted Mike. “One of us always had to stay with mom to do the household chores.” For the young boys, as much as they loved their mother, that assignment was not high on the list of what they wanted to be doing on their Saturday mornings.

The lists of chores might have been long, but Dr. Bailey was right there along with his boys, getting things done. “He was always right there with us,” said Mike. “The chores weren’t just assigned.”

Perhaps it was that personal example that led Dr. Bailey’s sons to their own highly accomplished careers, as a doctor, a lawyer, engineers. “We were never told that we had to get better marks in school,” said Mike. “We were expected to spend one year at university, to get out, off the Island and to see what was out there in the wide world.”

“I don’t recall either of my parents ever raising their voices,” said Mike. Geof laughed, suggesting that perhaps their elder brothers Chris and Peter had paved the way for their younger siblings in that regard.

“We always ate late, around 8 pm after dad was finished at the hospital,” said Geof. “He would often head back after dinner.”

The wood got chopped, the sailboat waxed and painted, its brass fittings polished to a bright shine. For sailing was high on the list of Dr. Bailey’s greatest passions and his sailboat played a major role in both his social leisure and, quite tellingly, his professional life.

When Dr. Bailey needed to lure specialists to the Island, it was the offer of a jaunt aboard his sailing vessel that played a key role. He would convince the specialists to come to the Island for an outing on the sailboat, but the price was that they had to do a turn with their professional skills at the clinic.

In 1970 Dr. Bailey joined the Great Lakes Cruising Club and served as the Fleet Surgeon from 1992 to 2002 and as Port Captain until 2006. “He was a great man,” said Roy Eaton of Little Current, who worked with Dr. Bailey as they prepared a reception for the GLCC Rendezvous in the Port of Little Current. The sitting room at Little Current’s Spider Bay Marina is named in Dr. Bailey’s honour.

Dr. Bailey never wasted time, his sons noted. “He could not sit still,” said Mike. “He was always very pragmatic,” added Geof. “He never wasted time.”

Manitoulin Transport founder Doug Smith and his wife Phyllis often joined Dr. Bailey and his wife on the boating jaunts, building a friendship that lasted up to the present day.

siblings, Alden, the youngest, Thelma and Howard.

“It was Phyllis who first met him when he came to the Island,” said Mr. Smith. “Doc Bailey’s wife Joyce was her teacher and Phyllis was one of his first patients.” Dr. Bailey didn’t call Phyllis Smith into his office to check her for that pre-vaccination scourge in the late 40s and 50s. “He got in his car and drove to Gore Bay to see her,” said Mr. Smith.

Later, Dr. Bailey accompanied Ms. Smith to Little Current during complications she was having during pregnancy. Again, making his way to his patient’s bedside and travelling with her to the hospital himself.

That theme has played out through interview after interview and through the pages of The Expositor, a subtext to each and every award and accolade accumulated by the driven doctor through his life of service to Manitoulin.

Whether it is talking to nurses, such as Jean Cunningham of Little Current or Rose Fraser (nee Corbiere of Wikwemikong, now living in Espanola), or local doctors like Dr. Bailey’s Scottish import the now-retired Dr. David Stephen or the mantle-bearing Dr. Roy Jeffery, his commitment to his patients shines through.

“Dr. Bailey contacted me after I filled out a form through the Canadian consulate in Glasgow at the time,” recalled Dr. Stephen. Dr. Stephen, who had trained as a surgeon but who was hitting a bureaucratic ceiling with the British health system of the day, was contemplating emigrating to Canada or Australia, but Canada was winning out. “I got a call from Jack, it was about three in the morning, he had forgotten about the time difference,” recalled Dr. Stephen. Once Dr. Stephen had shaken out the early morning cobwebs, they had a nice chat. “He told me about Manitoulin, that the sun shone every day,” chuckled Dr. Stephen. “He made Manitoulin sound like a nice place to come. He got in touch with a couple of other places and they decided to pay my way to come to Canada for a visit.”

La Pas, Manitoba was in the running, recalled Dr. Stephen, but he visited Manitoulin first. Dr. Bailey almost let his passion scare the Scot off. “It was very early in the year, the water had just opened up, and he had gotten a hold of a power boat,” said Dr. Stephen. “I thought I was pretty well bundled up.”

Dr. Bailey convinced the new doctor that if it was surgery he wanted, the local hospital was starting to “get into that kind of thing.”

It worked out well in the end. “I didn’t much care for La Pas,” said Dr. Stephen. “I was used to hills and being near the water.” Dr. Bailey did the anesthesia for most of the surgeries that Dr. Stephen went on to perform, until the arrival of Dr. Jeffery.

Dr. Bailey was the founder of today’s Little Current Medical Associates, now a family health team, and Dr. Jeffery has taken on the role of physician to the housebound that Dr. Bailey did as part of his practice for many years.

“A lot of people do not realize that a part of his legacy is the quality of care that we enjoy here in eastern Manitoulin,” said Dr. Jeffery. “He played no small part at all. It is extremely due to his character as a physician. We are all so much better physicians because of his example.”

Dr. Jeffery noted that Dr. Bailey never let up on his dedication to lifelong learning. “He kept up to date,” he said. “He always emphasized that with our students. Graduating from medical school is just the beginning.” Even following his retirement, Dr. Bailey kept up to date, asking questions and continuing to learn long after most doctors would have hung up their stethoscopes for good. “He had a profound effect on my practice.”

Among the things that Dr. Bailey had always stressed throughout his practice was the need to understand and respect Native traditions and culture, continued Dr. Jeffery. “He always impressed upon each of us the importance to First Nations people that we come to their communities, so that they didn’t have to come to us.”

Dr. Bailey developed a rapport with the late John Wakegijig, the Wikwemikong chief and later with Chief Wakegijig’s son Ron. The latter interaction developed into a friendship and collaboration that was to have a far-reaching impact on the delivery of medical treatment of the Anishinaabe. Dr. Bailey and Ron Wakegijig would prove to be pathfinders in the reconciliation and integration of First Nation traditions and culture with Western medical practice and delivery.

“We could write volumes about those two,” laughed the late Chief Wakegijig’s wife Rosemary. “They were two partners in crime.”

Ms. Wakegijig cited an occasion when Dr. Bailey gave his own blood to a Native person Dr. Bailey thought he was in danger of losing as just one example of the type of commitment and acts of caring that won the hearts of the residents of Wikwemikong.

Dr. Bailey was presented with an eagle feather and became the only white person to be officially named an honourary chief of the band during a special ceremony, said Ms. Wakegijig. “He was given the name Gaikezheyongai, Swift Wing, and that was the name he gave to his sailboat,” she recalled.

The two medical men, Dr. Bailey of the Western tradition and Chief Wakegijig of the Anishinaabe tradition, travelled to St. Mary’s in the US to learn how to incorporate First Nation traditions into the new medicine lodge that was to be included in Wikwemikong’s new medical centre, a ground-breaking innovation at the time and one that served as the model for the healing lodge that was much later incorporated into the new hospital facility being built in Sudbury.

“Doc Bailey and Ron crisscrossed the country, travelled all over Canada, out to Alberta and beyond working on their projects,” said Ms. Wakegijig. “I think that over the years of his practice, in what he witnessed, he came to believe the spiritual part,” she said. “He began to understand the power of our way of healing.”

Dr. Bailey and Chief Wakegijig developed a mutual respect and connection that transcended their differences. “Oh they had plenty of arguments,” laughed Ms. Wakegijig. “They were both men with very strong ideas.”

Chief Wakegijig’s daughter Dr. Annalind Wakegijig, who now practices in Echo Bay, cites Dr. Bailey as one of the inspirations and role models in her decision to pursue a medical career.

Dr. Bailey, whose practice took him to many tar paper and wooden shacks, often on snowmobile in the winter time, saw too many impoverished people living in abysmal conditions and he developed a vision of a retirement home on Manitoulin where people could live out their final years in dignity.

It was no easy task to build Manitoulin Centennial Manor. Although everyone agreed to the need, the competition to house the new facility brought forth some Byzantine machinations that did not prove to be the equal to the Manor board chair Doc Bailey and his allies; men like the redoubtable Barney Turner, whose political connections ran deep into the halls of power at Queen’s Park, and Little Current mayor John Farquhar, whose brother Stan Farquhar was the MPP, rallied to the cause.

“I think it finally came down to it was going to be here or it wasn’t going to happen,” said Mr. Turner’s son Jib. “My dad was working on the new hospital and Jack was working on the Manor.” The two visionaries worked on their projects separately but kept in close contact. The two men and their families were also very close personally. “Jack kept a photograph of my father on his desk.”

Debby Turner, Jib’s wife, was among those who kept a close watch on Dr. Bailey as his health finally failed, visiting him daily at the Manor in his final days.

Dr. Bailey worked diligently on an Order of Ontario nomination for his friend Mr. Wakegijig, an award he had himself received a few years earlier. The award was presented to Chief Wakegijig while he was on his own deathbed in the hospital; something that Dr. Bailey remarked gave him more satisfaction than his own.

Dr. Bailey travelled to his Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Award with fellow award recipient and boating companion Mr. Smith. “You can tell which one in the picture is Dr. Bailey,” noted Expositor writer Petra Wall, who is working on a small book on the physician’s life. “He is the one with the big smile.”

Dr. Bailey’s sense of humour was nearly as legendary as his medical acumen. Nurse Rose Fraser recalled many of the practical jokes the hospital staff played on each other to fend off the long working hours. One day Dr. Bailey had slipped out into the night to trim a tree branch and hid in the supply closet, rattling the branch in the wee hours of the night and moaning. The male nurse working the upper floor was sent for to investigate. “He found Doc Bailey in there rattling that branch around,” laughed Ms. Fraser. “He was lots of fun,” agreed Ms. Cunningham.

Ms. Cunningham recalled Dr. Bailey sending poor Sister Mary Agnes, one of the nursing sisters, out to raid the Flett’s garden. “She was running back and forth in between the rows and he was following her with the flashlight,” laughed Ms. Cunningham.

The bit of tomfoolery was an essential part of relieving the terrible trauma they often witnessed. The two nurses recalled when the daughter of one of their own came into the hospital after a serious car accident. Loaded into the back of a stationwagon, Ms. Fraser worked a makeshift breathing apparatus while Dr. Bailey lay beside the patient desperately working to try to save her life.

They were not successful. “Doctor Bailey took it terribly hard when he lost one of his patients,” said Ms. Cunningham.

Rural doctors often had to work with very rudimentary equipment and often perform well outside their comfort zones. “I remember Dr. Bailey doing an emergency surgery with me holding the book open for him while old Doc Henry did the anesthetic,” said Ms. Cunningham. “It wasn’t anything like today.”

Not all the old stories had a tragic end, in fact, there are many, many stories of unlikely success under incredible circumstances. On another occasion a young boy had been hit by a car falling down an embankment, the passenger train had already left the Island and the passenger car was full. The conductor was notified by emergency radio and stopped on the other side of the Little Current Swing Bridge. Dr. Bailey drove his young patient out to the train and he was loaded into the baggage car.

He called it his “ride of agony” as the baggage car was not equipped for comfort or passengers and Dr. Bailey struggled to keep the young man alive. The child survived and Dr. Bailey took great delight in following his progress through life.

In 1989, the College of Family Physicians of Canada recognized Dr. Bailey, by then 66 but still going strong in his practice, as Family Physician of the Year. When the phone call came to tell him of the award, his first response had been “Oh my God, what have I done now?” he said at the time. He thought that perhaps he had forgotten to send in the paperwork for his study hours. “I would have felt honoured that they thought that much of me to nominate me,” he said. “That would have been an honour in itself.”

Dr. Bailey was famed for making his rounds with pipe stem in mouth, during the days when smoking was more common than not in the hospital, and he loved a game of bridge. “He was a…cautious player,” ventured Little Current’s Cam Spec, who first met the doctor and his wife shortly after arriving on the Island. Mr. Spec recalled going fishing with the doctor and some friends just after a hernia operation. “I still have the picture of us with all of the fish we caught that day,” he said. It was all right, of course, he had his doctor with him.

In his final years Dr. Bailey struggled with a number of serious personal and health challenges, meeting each with what those who knew him best described as an amazing grace and fortitude. His wife preceded him into Manitoulin Centennial Manor when her decline finally made it impossible for the increasingly frail doctor to continue to look after her. His failing hearing had begun to isolate Dr. Bailey from the community and people he loved. It was an incredibly unfair impediment to a man for whom conversation and debate were central parts of his character, but he threw his medical research skills into the battle, adopting the latest in hearing technology as it became available and taking great delight in explaining its workings to friends and acquaintances he met while out and about.

Despite the increasingly challenging hands he was dealt healthwise, to the very end Dr. Bailey maintained his sense of humour and whimsical point of view.

“I hope they are taking good care of you here,” said Mr. Turner to the doctor during a visit shortly before his death. “After all, you built the place.”

“Well now,” retorted the doctor, “that explains why they have my picture all over the walls in here.”

Anishinaabek Nation Grand Chief Pat Madahbee, one of the many patients Dr. Bailey brought into the world, speaks for many of those in communities all across Manitoulin Island as they bid farewell to old Doc Bailey: “This extraordinary man of medicine brought me into this world as so many of us on the Island. He was a dedicated, skillful, compassionate professional who embraced traditional medicine with his own practices. He was one of the best.”