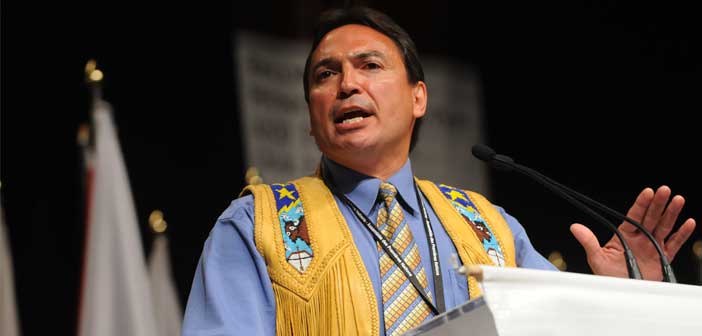

OTTAWA—Newly elected Assembly of First Nations (AFN) National Chief Perry Bellegarde admits that the road ahead for the AFN in the coming years is paved with plenty of challenges, but he said that same road also presents “a lot of opportunities.”

The national chief sat down with The Expositor in an exclusive interview last week to discuss those challenges and opportunities and how he plans to helm the AFN to meet the challenges and maximize the benefits of any opportunities that present themselves on the road ahead.

“One of my goals is a review of the AFN charter,” he said. “It needs to be analyzed to see what is working and what can benefit from change.”

Chief Bellegarde is no stranger to First Nations representation at the national and regional level and he is well aware of the unique challenges that face any national chief of the AFN. Unlike most non-Native national leaders, such as the Canadian prime minister or the provincial premiers, the national chief of the AFN does not wield direct power, but must instead build a strong consensus within the assembly of chiefs for any course or position he takes in negotiations. The Expositor asked how that is accomplished.

“In a very respectful way,” he said. “You listen and concentrate on the directions coming from the assembly. When you do that, you can get things done.” In order to accomplish the AFN’s goals the contribution of the national chief must be both respectful and relevant.

The key to success as national representative, he said, is to recognize that “it is really a team agenda.”

That is no mean task when there are 639 members comprising 58 different language groups.

The national chief said that his focus moving forward remains the same as the direction he outlined in his election platform. “Establishing a new fiscal relationship with the federal Crown; an immediate action plan and inquiry into missing and murdered indigenous women and girls; committed focus on the revitalization and retention of indigenous languages; and upholding indigenous rights as human rights in international forums.”

There are definite commonalities in the issues facing all First Nation communities through which a revisited national framework, one respecting all of the regions, can address, noted Chief Bellegarde. Among the most pressing of those commonalities is “closing the funding gap,” said the National Chief. “All of the funding agreements have been frozen at two percent for almost 20 years,” noted Chief Bellegarde. The result has been steady erosion in the ability of First Nation communities to meet the needs of their communities. “If that were to change there would be an immediate improvement.”

Chief among the consensus issues facing members of the AFN is the shortfall in education funding between the federally funded First Nations and the provincially funded education system.

International socio-economic measures place Canada sixth in human development, noted Chief Bellegarde, but those same measures applied to First Nations communities drop to 63rd. “That is the gap that needs to be addressed,” he said. “Even if you can’t get your head around treaty rights,” Chief Bellegarde addressed to non-Natives, “get your head around the business case.”

The treaty relationship between Canada and the First Nations was and is supposed to be of mutual benefit. “Get your head around aboriginal rights and talks as a good thing, because treaty implementation is good for everybody.”

Key to the discussion of self-determination is the economic well being of First Nations communities. “You can’t talk about self determination without talking about the economic development of Canada’s abundant resources.” The two, he points out, are intrinsically linked.

“As indigenous people, we have the inherent right to self-determination,” said Chief Bellegarde. “That means the ability to say ‘yes’ to development or ‘no’ to development.”

He cited the recent Tsilhqot’in (William Case) Supreme Court decision pointing out that the case can “be levered as one of several means by which to enshrine the meaning and intent of aboriginal title. It will pave the way to a new relationship between First Nations and the Government of Canada and reinforce the need for provincial and federal governments to consult and accommodate, resulting in the entrenchment of a pivotal role of First Nations in resource development.”

Chief Bellegarde has been cited as being among that group of First Nation leaders who maintain that the existing treaties are sufficient to protect aboriginal rights, provided those contracts are upheld and properly enforced on both sides.

“Recent high profile Supreme Court decisions and other events have created an unprecedented opportunity to elevate public awareness of inherent and treaty rights,” he said. “It also means that AFN success in communicating these issues has never been this important.”

Education of the general population about treaty rights is a key component of building the environment to address First Nations issues, he noted, particularly in Canada’s urban and immigrant populations, where the lack of information about the history of the treaty relationship, the contributions of First Nations to the development of Canada, and the history of the residential school system in school curriculums plays a major role in misunderstanding between the two communities.

Chief Bellegarde pointed to his home province of Saskatchewan as an example of how that dearth can be addressed. “In Saskatchewan, every school teaches aboriginal rights, every school, that is where you get to start changing things.”

While his business oriented approach heralds an opportunity to negotiate and settle the plethora of grievances facing intergovernmental and economic relations between Canada and the First Nations and building a new relationship based on existing treaties, Chief Bellegarde had a stern warning for those who believe that they can continue to exploit or ignore First Nations.

“Governments want economic certainty,” he said. “There is $650 billion in potential resource development projects in Canada and government wants to export those resources to foreign markets. What we are saying is if you want to continue to do that, and to create economic certainty, you need to involve indigenous peoples every step of the way.”

If that involvement does not happen in a meaningful and productive way, he warns that Canada’s economic road ahead will prove to be a very rocky experience.